Women make more attempts at suicide than men. But men actually die by suicide at a rate “that is 3.0 to 7.5 times that of women.” Despite that fact, literature has always depicted more suicidal women. Dr. Elise P. Garrison, Professor of Classical Studies, cataloged more than 60 female suicides in Greek and Roman mythology alone. Dido, Lucretia, Ophelia and Cleopatra are widely known examples.

It has always been an obsession and a taboo to have young women kill themselves in works of fiction, most of which were penned by men. But there are signs that even as more women entered the realm of fiction writing in the 19th century, they continued the morbid tradition of killing their heroines as evident with great authors like Kate Chopin or George Eliot (aka Mary Anne Evans). Without much difficulty, one could find examples in novels of the 20th century such as Passing (1929) by Nella Larsen. Perhaps Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) tried to understand it when he said:

The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.

This phenomenon goes much further beyond literature, into paintings, movies and advertising.

Many studies and analyses have been conducted to figure out the reasons behind the public fascination with female suicide in fiction. Explanations vary and there might never be consensus or a unified theory. One approach is to investigate each period individually. Regarding the 19-century in particular, a question could be formulated like this:

Why unhappy wives in 19th-century classic novels committed suicide as in Madame Bovary (1857) by Gustave Flaubert, The Awakening (1899) by Kate Chopin and Anna Karenina (1877) by Leo Tolstoy?

What binds together the women (Emma, Edna and Anna respectively) of the above mentioned novels is the following…

a. They’re all middle-class wives and mothers

b. They’re miserable and bored with their domestic lives

c. They’re vivacious, full of sensual desire yet confined by society

d. Their husbands fail to satisfy their needs in most ways

e. They all engage in adultery

f. Their portrayal is sympathetic, with an emphasis on their personal misery

g. They all finally commit suicide

Although these characters are fictional, they represent countless women of their era. For these particular wives, suicide seemed like their only exit because:

1. Not only were most social and religious institutions of no help to women, but in fact they were oppressive too. The all-male positions of power such as the clergy, lawyers, professors and even doctors rarely understood women and their needs, and hence were not willing to look into their marital difficulties. When Emma Bovary was so miserable in her marriage that it was affecting her physical health, she went to seek help from a priest and his response before he walked away was

“It’s indigestion, I expect? You ought to be at home, Madame Bovary, with a nice cup of tea; it’ll pick you up, or a glass of cold water with some brown sugar.” 1Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary: Provincial Lives, trans. Geoffery Wall (London and New York: Penguin, 1992), 63.

2. Something important happened to women in the West during the 1800s: It’s true that they were not legally separate from their husbands and the right to vote would only be granted at the turn of the century. Also, their husbands, as much of society, treated them as children who misbehave at times, gave them allowances since they don’t work (or rather, have no right to) and administered occasional discipline and beatings. However, it was during that century that they developed a new kind of self-consciousness. It was a period when women gained a voice to demand changes which anticipated the first wave of feminism, from the 1900s to 1950s. That coincided with writers, of both genders, joining the movement of Realist fiction to give readers a daily insight into why women are frustrated with their marriages. Edna Pontellier in The Awakening expressed that in what seemed like an enigmatic line.

I would give up the unessential; I would give my money, I would give my life for my children; but I wouldn’t give myself. 2Kate Chopin, The Awakening Thrift Study Edition (Chicago and New York: Herbert S. Stone & Co., 1899; reprint, Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2010), 47.

She means to say she is willing to give up anything except her own identity as a woman and her right to her own thoughts and affections.

For women (and any subjugated group) to open up their eyes and develop more awareness of their own oppression was a psychologically severe process which had an opposite effect and pushed many into hopelessness. They recognized how horrible their conditions were while they could not foresee any solutions. No wonder Madame Bovary wished that it wouldn’t be a girl when she learnt she’s pregnant:

She wanted a son […] A man, at least, is free; he can explore each passion and every kingdom, conquer obstacles, feast upon the most exotic pleasures. But a woman is continually thwarted. 3Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary: Provincial Lives, trans. Geoffery Wall (London and New York: Penguin, 1992), 82.

3. Divorce was very difficult to obtain. A woman divorced lost her home, her provider and her children. The husband always got full custody of children. A divorced woman faced a real possibility of being homeless, besides a life-long stigma around family and society. That is the reason why many wives stayed in physically abusive relationships. The alternative was life on the streets!

4. Writers penned their tales within the moral frameworks of their times. Adulteresses had to be condemned and punished in their view. Also, writers had no common precedent based on reality in their own societies where wives and mothers would move on to thrive after “abandoning” their own families. And even if that existed and was common, they would have been hesitant to portray it. They had enough trouble (legal in some cases) as it was by just reciting tales of infidelity.

5. An easy and age-old literary method (some critics call it lazy or vile) was to bring a resolution to the narrative of a cheating wife by having her kill herself. In the author’s eyes, that was the only salvation available for a “fallen” woman.

The three novels discussed here are not the only ones featuring such themes. Lesser known 19th century examples exist, like Hedda Gabler (1891) by Henrik Ibsen which also featured a wife who’s unsatisfied in her marriage and eventually commits suicide. Unhappy marriages and the representation of the triangle of women, sex and death in other forms is found in even more works like Daniel Deronda (1876) by George Eliot and Effi Briest (1895) by Theodor Fontane.

Some modern critics take issue with authors, especially male ones, for killing their victimized heroines who dare to be different. They find it objectionable and sexist. For example, a writer for The Guardian wrote under the title “Anna Karenina: great novel, shame about the ending“: the one woman who attempts to transgress these boundaries ends up committing suicide.

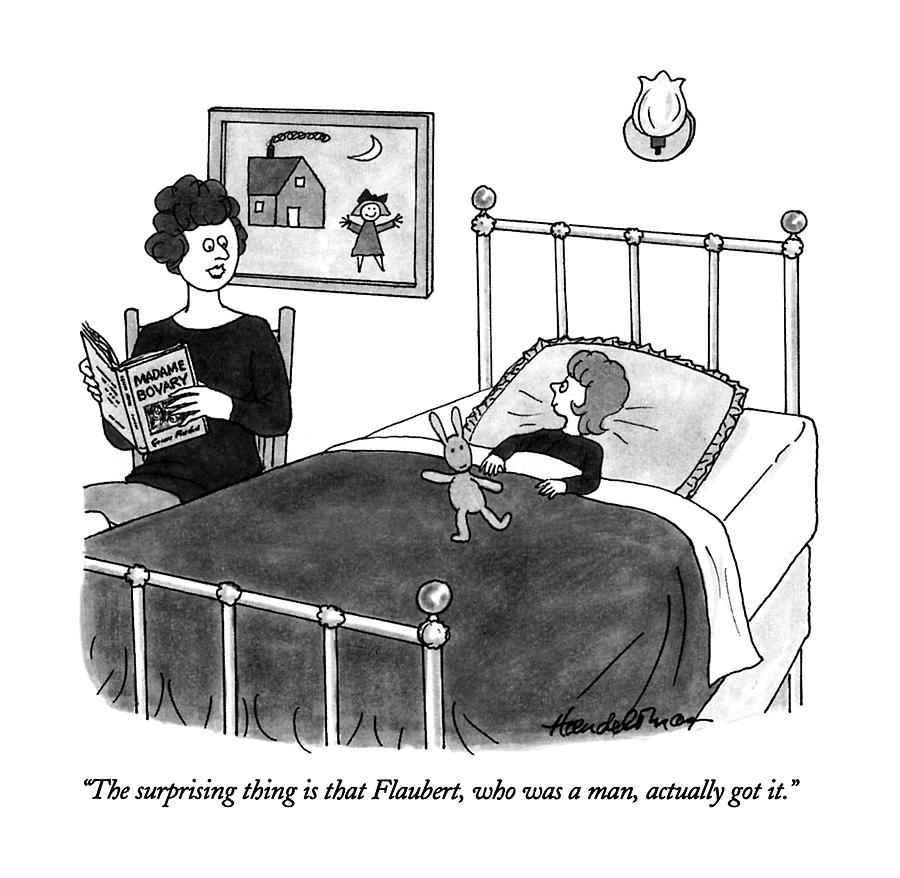

Fortunately, the majority of readers still appreciate how these Realist writers painted for the public an honest picture of the many women who felt hopelessly trapped in joyless marriages. One of them was a cartoonist in the New Yorker (by the way, I don’t recommend you read Madame Bovary to your child as a bedtime story!):

If the subject of suicidal wives seems irrelevant to you or just the stuff of classic fiction, then you’re probably not aware of the following fact: more than 20,000 housewives have been killing themselves in India every year since 1997. Millions of wives are still subjugated around the world. They can neither attain marital life with dignity nor walk away peacefully.

You might also like:

Madame Bovary: The scandalous scenes

Why Gustave Flaubert was put on trial for Madame Bovary?

BOOK: MADAME BOVARY

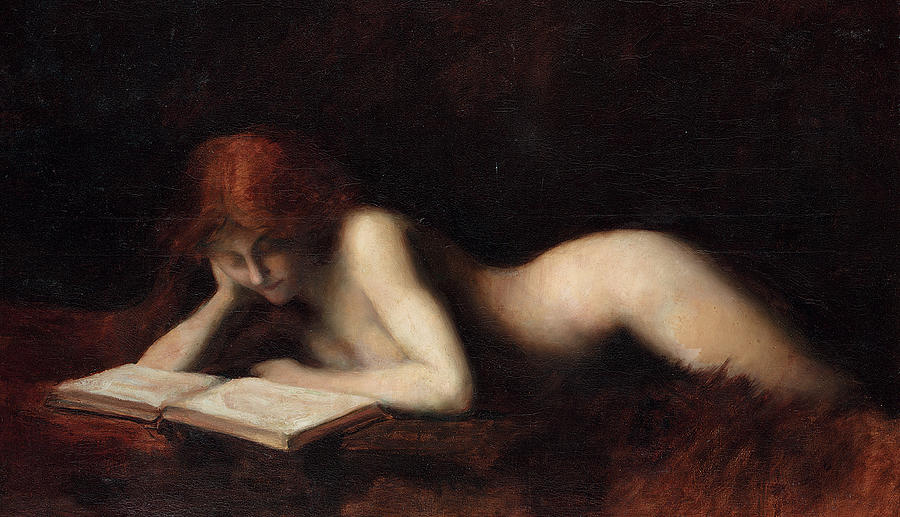

Through art: Sexist views of women who read from yesteryear

What art can tell us about the social anxiety towards women who read

BOOK: MADAME BOVARY

Endnotes