At the age of eleven-going-on-twelve, Margaret moves with her parents to the suburbs of New Jersey, after living her entire young life in New York City. Besides the common anxieties of an early-adolescent girl, about bras, periods and boys, she is also trying to figure out which religious affiliation she should join. Because her mother is Christian and her father is Jewish, they decided to leave their daughter the freedom, and the challenge, of deciding on religion on her own. She has a “personal connection” with God which she experiences at the end of her day in brief prayers that always start the same way:

Are you there God? It’s me, Margaret. I just told my mother I want a bra. Please help me grow God. You know where. I want to be like everyone else. You know God, my new friends all belong to the Y or the Jewish Community Center. Which way am I supposed to go? I don’t know what you want me to do about that. 1Judy Blume, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, (New York: Atheneum, 1970; Reprint edition, 2014), 42.

Margaret has a crush on a boy, Moose Freed, who was hired by her father to mow their lawn. She quietly watches him at work. She also becomes friends with Nancy, Gretchen and Janie and together they form their own secret club to discuss “girl stuff.” They called their club “The Pre-Teen Sensations” (PTS’s). They’re all going through puberty and expecting their periods soon. Nancy is the most confident of them and usually talk like a know-it-all about boys, sex and bras. She suggests a simple exercise believing it could increase the size of their busts:

“Like this,” Nancy said. She made fists, bent her arms at the elbow and moved them back and forth, sticking her chest way out. She said, “I must—I must—I must increase my bust.” She said it over and over. We copied her movements and chanted with her. “We must—we must—we must increase our bust!” 2Ibid., 53.

Later, on her own…

Are you there God? It’s me, Margaret. I just did an exercise to help me grow. Have you thought about it God? About my growing, I mean. I’ve got a bra now. It would be nice if I had something to put in it. Of course, if you don’t think I’m ready I’ll understand. I’m having a test in school tomorrow. Please let me get a good grade on it God. I want you to be proud of me. Thank you. 3Ibid., 57.

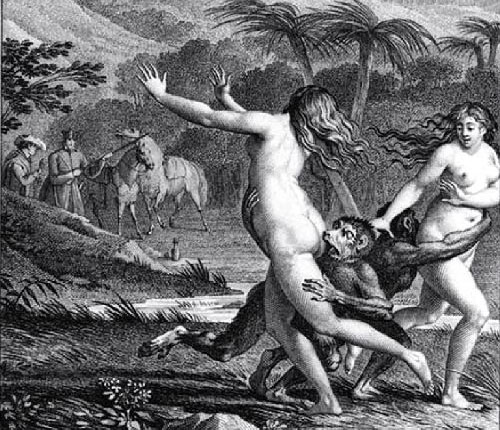

In one of their “secret club” meetings, they talked about nudity:

“My aunt went to a nudist colony last summer,” Janie said.

“No kidding!” Nancy looked up.

“She stayed a month,” Janie told us. “My mother didn’t talk to her for three weeks after that. She thought it was a disgrace. My aunt’s divorced.”

“Because of the nudist colony?” I asked.

“No,” Janie said. “She was divorced before she went.”

“What do you suppose they do there?” Gretchen asked.

“Just walk around naked is all. My aunt says it’s very peaceful. But I’ll never walk around naked in front of anybody!” 4Ibid., 79-80.

Then Margaret was challenged into temporarily stealing her father’s porn magazine, which she does:

“When you grow you’ll change your mind,” Nancy told her. “You’ll want everybody to see you. Like those girls in Playboy.”

“What girls in Playboy?” Janie asked.

“Didn’t you ever see a copy of Playboy?”

“Where would I see it?” Janie asked.

“My father gets it,” I said.

“Do you have it around?” Nancy asked.

“Sure.”

“Well, get it!” Nancy told me.

“Now?” I asked.

“Of course.”

“Well, I don’t know,” I said.

“Listen, Margaret—Gretchen went to all the trouble of sneaking out her father’s medical book. The least you could do is show us Playboy.”

So I opened my bedroom door and went downstairs, trying to remember where I had seen the latest issue. I didn’t want to ask my mother. Not that it was so wrong to show it to my friends. I mean, if it was so wrong my father shouldn’t get it at all, right? Although lately I think he’s been hiding it because it’s never in the magazine rack where it used to be.

Finally, I found it in his night table drawer and I thought if my mother caught me and asked me what I was doing I’d say we were making booklets and I needed some old magazines to cut up. But she didn’t catch me.

Nancy opened it right up to the naked girl in the middle. On the page before there was a story about her. It said Hillary Brite is eighteen years old.

“Eighteen! That’s only six more years,” Nancy squealed.

“But look at the size of her. They’re huge!” Janie said.

“Do you suppose we’ll look like that at eighteen?” Gretchen asked.

“If you ask me, I think there’s something wrong with her,” I said. “She looks out of proportion!”

[…]

Our meeting ended with fifty rounds of “We must—we must—we must increase our bust!” 5Ibid., 80-82.

The role and place of religion in her family continues to be unclear to Margaret:

The next week my mother started to address her Christmas cards and for days at a time she was frantically busy with them. She doesn’t call them Christmas cards. Holiday greetings, she says. We don’t celebrate Christmas exactly. We give presents but my parents say that’s a traditional American custom. 6Ibid., 84.

In school, the minor conflicts over religion complicates matters for her.

Alan Gordon told Mr. Benedict that he wasn’t going to sing the Christmas songs because it was against his religion. Then Lisa Murphy raised her hand and said that she wasn’t going to sing the Hanukkah songs because it was against her religion.

Mr. Benedict explained that songs were for everyone and had nothing at all to do with religion, but the next day Alan brought in a note from home and from then on he marched but he didn’t sing. Lisa sang when we marched but she didn’t even move her lips during the Hanukkah songs.

Are you there God? It’s me, Margaret. I want you to know I’m giving a lot of thought to Christmas and Hanukkah this year. I’m trying to decide if one might be special for me. I’m really thinking hard God. But so far I haven’t come up with any answers. 7Ibid., 86.

Ahead of a class dinner party, she had a bath to get ready, then she inspected herself for any prospects of pubic hair or other changes:

What I did was move my desk chair in front of my dresser mirror. Then I stood on the chair and took off my robe. I stood naked in front of the mirror. I was starting to get some hairs. I turned around and studied myself sideways. Then I got off the chair and moved it closer to the mirror. I stood back up on it and looked again. My head looked funny with all those rollers. The rest of me looked the same. 8Ibid., 93.

Then she jumped off her chair and put on her underwear and a bra. She went back to the bathroom to get cotton balls:

I tiptoed back to my room and closed the door. I stepped into my closet and stood in one corner. I shoved three cotton balls into each side of my bra. Well, so what if it was cheating! Probably other girls did it too. I’d look a lot better, wouldn’t I? So why not!

I came out of the closet and got back up on my chair. This time when I turned sideways I looked like I’d grown. I liked it!

Are you still there God? See how nice my bra looks now! That’s all I need—just a little help. I’ll really be good around the house God. I’ll clear the table every night for a month at least! Please God… 9Ibid., 94.

At the party, they play a game similar to Spin the Bottle, where each person gets to spend two minutes behind a closed bathroom door with someone else. Her luck matches her up with Philip, a popular boy she had a crush on before.

I was half scared and half excited and I wished I had been experimenting like Nancy. Nancy would know what to do with a boy in the dark, but what did I know? Nothing! 10Ibid., 103.

He put his hands on my shoulders and leaned close. Then he kissed me. A really fast kiss! Not the kind you see in the movies where the boy and girl cling together for a long time. While I was thinking about it, Philip kissed me again. Then he opened the bathroom door and walked back to his place. 11Ibid., 105.

Gretchen was the first of the four to get her period. They assembled specially for that occasion.

“Well, I was sitting there eating my supper when I felt something dripping from me.” 12Ibid., 112.

They pressured her to divulge more information:

“Mostly I don’t feel anything. Sometimes it feels like it’s dripping. It doesn’t hurt coming out—but I had some cramps last night.” 13Ibid., 114.

Nancy did not hide her jealousy. Margaret was even more stressed out and discussed it with her mom:

“I’m afraid there’s not much you can do about it, Margaret. Some girls menstruate earlier than others. I had a cousin who was sixteen before she started.”

“Do you suppose that could happen to me? I’ll die if it does!”

“If you don’t start by the time you’re fourteen I’ll take you to the doctor. Now stop worrying!”

“How can I stop worrying when I don’t know if I’m going to turn out normal?”

“I promise, you’ll turn out normal.”Are you there God? It’s me, Margaret. Gretchen, my friend, got her period. I’m so jealous God. I hate myself for being so jealous, but I am. I wish you’d help me just a little. Nancy’s sure she’s going to get it soon, too. And if I’m last I don’t know what I’ll do. Oh please God. I just want to be normal. 14Ibid., 115.

Nancy had told Margaret lies about a fully developed girl named Laura. Nancy spreads a rumor that Laura makes out with another guy. One time, Margaret loses her patience with Laura at the library and she confronts her with her lewd behavior with boys:

“I don’t know what you do it for. But I know why they do it … they do it so they can feel you or something and you let them!” 15Ibid., 133.

Laura was shocked and denied all rumors. Nancy felt guilty afterwards.

Throughout the story, Margaret tells us that she likes her paternal grandmother. We learn that she’s Jewish, sweet and likes to spoil Margaret. She talks and listens to the heroine of the story more than anyone else. The maternal grandparents make a less-than-joyful appearance in the last few chapters of the book. They had disowned Margaret’s mother, Barbara, in disapproval of her marriage to a Jewish man. They are conservative Christians. After many years of alienation, Barbara yearned to contact her parents and sent them a Christmas card. Now they know her address. They responded with a letter that they’ll drop by for a visit.

My father shook the letter at my mother. “So now, after fourteen years—fourteen years, Barbara! Now they change their minds?” 16Ibid., 140.

Not only was the father upset, but also Margaret was furious. She had planned to visit her grandmother who had moved to Florida. Now that plan was cancelled.

“Mom!” I cried. “You can’t do this to me. You can’t! It’s not fair—it’s not!” I hated my mother. I really did. She was so stupid. What did she have to go and send them a dumb old card for! 17Ibid., 143.

Barbara defended herself to Margaret’s father:

“Look, Herb,” my mother said. “I haven’t forgiven my parents. You know that. I never will. But they’re coming. I can’t say no. Try to understand … both of you … please.” 18Ibid., 147.

During the sudden visit, Margaret’s grandmother asked her about Sunday School:

“I don’t go to Sunday school,” I said.

“You don’t?”

“No.”

“Father … (That’s what Grandmother called Grandfather. He called her “Mother.”)

“What is it, Mother?” Grandfather said.

“Margaret doesn’t go to Sunday school.” Grandmother shook her head and played with her cross.

“Look,” my mother said, trying a smile. “You know we don’t practice any religion.”

Here it comes, I thought. I wanted to leave the room then but I felt like I was glued to my seat.

“We hoped by now you’d changed your minds about religion,” Grandfather said.

“Especially for Margaret’s sake,” Grandmother added. “A person’s got to have religion.”

“Let’s not get into a philosophical discussion,” my father said, annoyed. He sent my mother a warning look across the room.

Grandfather laughed. “I’m not being a philosopher, Herb.”

“Look,” my mother explained, “we’re letting Margaret choose her own religion when she’s grown.”

“If she wants to!” my father said, defiantly.

“Nonsense!” Grandmother said. “A person doesn’t choose religion.”

“A person’s born to it!” Grandfather boomed.

Grandmother smiled at last and gave a small laugh. “So Margaret is Christian!” she announced, like we all should have known.

“Please … ” my mother said. “Margaret could just as easily be Jewish. Don’t you see—if you keep this up you’re going to spoil everything.”

“I don’t mean to upset you, dear,” Grandmother told my mother. “But a child is always the religion of the mother. And you, Barbara, were born Christian. You were baptized. It’s that simple.”

“Margaret is nothing!” my father stormed. “And I’ll thank you for ending this discussion right now.”

I didn’t want to listen anymore. How could they talk that way in front of me! Didn’t they know I was a real person—with feelings of my own!

“Margaret,” Grandmother said, touching my sleeve. “It’s not too late for you, dear. You’re still God’s child. Maybe while I’m visiting I could take you to church and talk to the minister. He might be able to straighten things out.”

“Stop it!” I hollered, jumping up. “All of you! Just stop it! I can’t stand another minute of listening to you. Who needs religion? Who! Not me … I don’t need it. I don’t even need God!” I ran out of the den and up to my room.

I heard my mother say, “Why did you have to start? Now you’ve ruined everything!”

I was never going to talk to God again. What did he want from me anyway? I was through with him and his religions! And I was never going to set foot in the Y or the Jewish Community Center—never. 19Ibid., 152-154.

The grandparents cut their visit short. Margaret was determined not to talk to God anymore like she used to.

Meanwhile she was losing her patience about not getting her period. She, who had been a good girl so far, decided to go and buy sanitary napkins behind her mother’s back. She acted like, not even God, could reign her in anymore:

Today I was feeling brave. I thought, so what if God’s mad at me. Who cares? I even tested him by crossing the street in the middle and against the light. Nothing happened. 20Ibid., 156.

Sheepishly, she went with Janie to make the purchase hoping no one would spot her and lied to her mother about the contents of her bag claiming they were school supplies:

I went to my room with my purchases. I sat down on my bed staring at the box of Teenage Softies. I hoped God was watching. Let him see I could get along fine without him! I opened the box and took out one pad. I held it for a long time. 21Ibid., 158.

Her grandmother who has been living in Florida dropped by for a surprise visit. She brought along, Mr. Binamin, a kind widower she had been dating. Margaret was excited to see her. She asked her about her the visit of her other grandparents. Margaret implied that they were pressuring her about being a Christian:

“Just remember, Margaret … no matter what they said … you’re a Jewish girl.”

“No I’m not!” I argued. “I’m nothing, and you know it! I don’t even believe in God!” 22Ibid., 162.

To Margaret’s disappointment, even her grandmother who has always been more understanding of her than others had the same attitude regarding religion. Even her felt entitled to choose for Margaret.

Finally, on the last day of school, Margaret gets her period.

I locked the bathroom door and peeled the paper off the bottom of the pad. I pressed the sticky strip against my underpants. Then I got dressed and looked at myself in the mirror. Would anyone know my secret? Would it show? Would Moose, for instance, know if I went back outside to talk to him? Would my father know it right away when he came home for dinner? I had to call Nancy and Gretchen and Janie right away. Poor Janie! She’d be the last of the PTS’s to get it. And I’d been so sure it would be me! How about that! Now I am growing for sure. Now I am almost a woman!

Are you still there God? It’s me, Margaret. I know you’re there God. I know you wouldn’t have missed this for anything! Thank you God. Thanks an awful lot… 23Ibid., 171.

Thus the book ends with Margaret reviving her personal connection with God, after having abandoned her original goal of joining a particular religion.

You might also like:

The Giver: The passages about euthanasia and suicide

Why the dystopian novel was considered inappropriate for its young audience? Read the passages on euthanasia and suicide

BOOK: THE GIVER

A Wrinkle in Time: Is it blasphemous or too Christian?

Two reasons Madeleine L’Engle’s book was challenged by religious conservatives

BOOK: A WRINKLE IN TIME

Endnotes