I’ve put together all the controversial passages in two articles. You could read the controversial parts on education below or do as younger readers of the 70s most likely used to do: skip to to the salacious parts of the second half of the book on sex and drugs.

Today The Little Red Schoolbook is rarely talked about even though it once created an international uproar. It was famous for its “obscenity” and for being a symbol of the anti-authoritarianism of the sixties. In a format of a reference book, it contained practical advice for young students (age 10 to 17) on many subjects from sex and drugs to organizing a strike and rebellion in school. All of that while encouraging them not to tell their parents. Decades after it was published, much of the advice in it sounds wise and already mainstream, perhaps except that which tells kids to read porn under their desks if bored! It’s best not to approach this book with a single attitude, be it “wholly objectionable” or “perfectly helpful.” Also, one has to recognize that in the pre-Internet era, teenagers must have appreciated the honest tone of the writers.

Note: The Little Red Schoolbook was first published in Denmark in 1969, then it was translated and published with information specific to countries such as Britain, Finland, Germany, Italy, Norway, Spain, Sweden and USA. The excerpts below are from the New Zealand edition.

The book opens with its best known and most infamous line:

All Adults are paper tigers

…

Tigers are frightening. But if they’re made of paper they can’t eat anyone. You believe too much in the power of adults, and not enough in your own capabilities.Kids and adults are not natural enemies. But adults themselves have little real control over their lives. They often feel trapped by economic and political forces. Kids suffer as a result of this. Cooperation is possible when adults have realised this and have started to do something about it.1Jesper Jensen and Soren Hansen, The Little Red Schoolbook: New Zealand edition, trans. Berit Thornberry (Copenhangen: Hans Reitzels Forlag A/S, 1969; revised and republished, Wellington, New Zealand: Alister Taylor, 1972), 9.

Using the same tone widely used by the counterculture movement, the writers first attack “the establishment,” or “the system”:

Whatever teachers and politicians may say, the aim of the education system in New Zealand is not to give you the best possible opportunity of developing your own talents.

The industries and businesses that control our economic system need a relatively small number of highly educated experts to do the brain-work, and a large number of less well educated people to do the donkey-work.

…

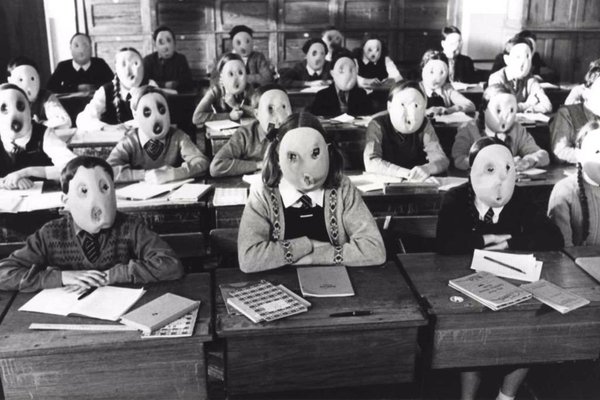

Instead of helping you develop as an individual schools have to teach you the things our economic system needs you to know. They have to teach you to obey authority rather than to question things, just as the exam system encourages you to conform, not to be an individual.2Ibid, 13-14.

[O]ften authorities insist on order for order’s sake. Sometimes this makes life simpler for them. Sometimes because they want to impose their own ideas of conformity—no long hair, no “crops”, no mini-skirts, no maxi-skirts, no talking in the corridor, lining up in the playground etc.3Ibid, 18.

On teachers:

Teachers are there to teach you not the things that you as an individual really need to know, but rather the things that other people think you ought to know.

Many teachers don’t really know the practical value of the things they teach you. They’ve learnt about them from books and they pass this knowledge on to you, without always explaining how and why it will be useful.

Many teachers have never done anything apart from teaching. As a result they may not know much about life outside school. Many of them come from a different social background to their pupils and were brought up at a time when the world looked different. As a result they may not understand you and your ideas about the different world you are being brought up in.4Ibid, 33.

Many teachers tend to blame other people when things go wrong. They invent theories about the youth of today being particularly difficult, or they blame it on bad working conditions, or on the principal, or on the parents. They maybe right. But they may just be making excuses for their own failings.5Ibid, 37.

Teachers are dogs on leads too

There shouldn’t really be any conflict between teachers and students. Teachers do have a lot of power, but even they are forced to do a lot of things which they may not want to do.

…

When it comes down to it, teachers have remarkably little control over their own lives—if they want to remain teachers, that is.6Ibid, 42-43.

Fifteen ideas to defy authority of school (as if students can’t come up with their own):

If you’re bored in lessons, remember that the teacher may be bored with the subject too. Try to get a discussion going on something different—and he may jump at the opportunity.

But if you really can’t persuade the teacher to make his teaching less boring, then you always have possibilities of escape. You know some of these possibilities very well:

–writing notes to each other;

–drawing on the covers of books;

–playing with your ruler and rubber;

–making paper planes under the desk;

–thinking about what you’re going to do after school;

–reading comics or thrillers or pornographic magazines under your desk.

…

–work out how you’re going to spend your pocket-money;

–plan your spare time;

–get together with someone else who’s bored and exchanges notes about a film or something on TV that interests you;

–write an article or a letter to a newspaper—perhaps about that particular lesson;

–read The Little Red Schoolbook;

–draw something in a book that looks like your exercise book; the teacher will thing you’re taking notes;

–write a poem on a book cover;

–write a letter you should have written long ago;

–write to us for example and describe the lesson. Our address is Box 10292, Wellington.7Ibid, 24-25.

On corporal punishment:

Corporal punishment in schools is obsolete and should be abolished. It’s been abolished in prisons and in the army and navy.

….

[BUT] parents and teachers still support the use of corporal punishment, both in school and out. It was used when they were children and they still think “a short, sharp lesson” is the best answer to any misbehaviour. In this respect, they treat kids as they would treat a dog which “misbehaved” on the carpet.8Ibid, 65.

It’s easy to underestimate how contrarian it once was to oppose corporal punishment. When The Little Red Schoolbook was published, the use of physical force to discipline children was legal around the world. But even today it’s prohibited in only 49 countries. Unsurprisingly, Sweden was the first to ban it in 1979.

There is no actual law governing the use of corporal punishment in schools…Under common law, teachers are regarded as being in loco parentis (bold font in original) to kids in their charge. This means that teachers have the rights and duties of a “normal, prudent” parent. Parents, and hence teachers, are legally entitled to physically punish a kid who misbehaves. They only break the law if the punishment is improper or excessive. There is no established definition of what “improper or excessive” actually means. As a result, it’s very rare for a teacher (even rarer for a parent) to actually get taken to court for excessive punishment.

Even if a teacher does get taken to court, the school authorities will usually support him. And the courts themselves often tend to have a distinctly old-fashioned view of what is excessive. They tend to be lenient with the teacher, unless the punishment has been really outrageous.

Courts also tend to use a rather wide definition of how far a teacher’s authority stretches. Courts have supported teachers who punish students for fighting on the way to school and for smoking at the pictures.

Regulation of the use of corporal punishment in schools is left to the principal. Some principals stipulate who is allowed to use corporal punishment and even specify the dimensions of the canes.

…

Time and time again it’s been shown that corporal punishment can do serious sharm to disturbed, backward or mentally handicapped kids. Yet it’s most frequently used on precisely these kids…What they want is more attention and encouragement. What they get is a slap and a caning.

…

If a teacher gives you a cuff round the ear (often quite unjustifiably) it doesn’t make you change your attitude and really pay attention: it just makes you resentful. If you get called to the principal’s office for a caning you may be a bit afraid and it will hurt for a while. But it doesn’t miraculously make you “see the light” and transform you into a “nicely behaved little boy”. At best it’ll make you try not to get caught again. And when it’s over, the chances are you’ll treat the whole thing as a big joke.

…

[I]f a teacher hits you brutally or keeps picking on your complain. If you’re given a major punishment, such as a lot of extra work or a caning, for something you didn’t do, or for something you genuinely didn’t know was forbidden, refuse to accept the punishment. Be prepared to take your case to a higher authority or to the press if necessary. Don’t let yourself be intimitated by any threats if you’re in the right.

…

You’re told often enough about your duties. Remember that you have rights too.9Ibid, 63-71.

So you’re writing a progressive book on education, sex and drugs in the late 60s. You know that book is guaranteed to be labelled “left-wing drivel” and you’re aware that leftists are often accused of being in the same camp with Communists. During that period the progressive hippie movement is sweeping the West and calling for reforms. It’s also a period when the US is still engaged in the Cold War and concerns over the worldwide spread of communism is bringing American troops into a long fight in Vietnam. Militants, allied with Communism, are forming terrorist groups such as Weather Underground in USA or the Baader-Meinhof Group in West Germany. Meanwhile China, under Communist Mao Zedong, is going through a bloody cultural revolution. Then what could be the most provocative design, and title, for such book?

The book’s pocket-sized design is inspired by Mao’s Little Red Book (first published in 1964), which had a gospel-like status during the Chinese cultural revolution. The red color of the book, whose real name is Quotations of Chairman Mao, had long been associated with the Communist movement. Also the infamous opening line of The Little Red Schoolbook is based on one of Mao’s quotations: “all reactionaries are paper tigers.”

On homework:

There are no laws which say how much homework you must do. You should make a fuss if you feel you’re being given too much homework to do.

Most teachers—and especially most parents—just can’t imagine that you can learn anything without doing homework. Tell them that in Sweden compulsory homework has been abolished.10Ibid, 30.

On internal exams:

Schools often use exams and tests to frighten you into working.

In some schools teachers believe that exams and tests can show exactly what you know. By far the greatest number of exams don’t show what you know. They often ask the wrong questions. They may show what you’ve learnt parrot-fashion or had knocked into you. They rarely show whether you can think for yourself and find things out for yourself.

You can’t rely on exam results at all. You’re not allowed to discuss the questions with your friends. You may be nervous or ill at the time. You don’t get enough time to think about the questions and write your answers. So it’s not the people who know most who do best in exams: it’s the people who are properly organised, can keep cool and can write fast.

In schools which have a lot of school exams and tests, education suffers. You don’t learn about the subjects themselves: you learn how to cope with tests and exams.

This can be changed

Most schools still have exams at the end of every term. This wastes a lot of time, both for students and teachers. Try to get a big discussion going between teachers and students about these exams, and see if you can’t get them abolished. It’s up to each school to decide.

If everybody seems to agree that it would be better to do without these exams but nothing actually gets done about it, try more direct methods. If possible, get everybody to simply boycott the exams altogether. If this is too difficult, everybody can turn up for the exams but simply hand in their papers blank. This will be a very effective way of getting the whole question properly discussed.

The school may agree to abolish, say, half-term or end-of-term exams, but insist on keeping end-of-year exams. If this can’t be changed, the exams can at least be arranged differently. Students can be allowed to bring notes and reference books into the exams, or the exams can be held in a library where you’re allowed to use the books during the exam.11Ibid, 160-162.

Tell them that in Swedish schools all public exams have been abolished. Ministry inspectors ensure that all schools keep up the same standards of teaching. Students do still get marks or grades, but these are based on all their work at school, not just on the results of a few hectic hours of exams.12Ibid, 164.

On external exams:

[I]t’s much more difficult to get rid of external exams. This would involve a basic change in the attitudes of most teachers and parents. A change this big will probably take many more years—but it will eventually come about.13Ibid, 164.

External exams are used at various levels of the education system to sort out the “sheep” from the “goats”. They’re used to decide who’ll go on into the sixth form and who’ll leave school. They’re used to decide who’ll go to university, training college or polytech and who won’t. There aren’t enough higher education facilities for everybody, so exams are used as a form of rationing.14Ibid, 162.

On marks:

Marks are used in schools as a kind of bribe, to get you to do things you don’t want to do. A system based on marks makes you work for the marks—not because you enjoy the work and find it interesting. In some schools marks become an end in themselves, just as money sometimes does in the outside world.

…

Marks can be a swindle. Marks can fool people—regardless of whether it’s other people or you yourself who are fooled.

…

Some teachers think that marks tell everything about a student. This is nonsense. Marks may tell you something, in a crude and clumsy way, about how much you’ve learnt in a particular subject. But marks tell you nothing about your ability. Ability can’t be counted like sheep or measured like wall-paper.15Ibid, 156-158.

Against marks

In most schools teachers are forced to give marks. The authorities demand marks so they can see how the teaching is going. And the exam system demands marks. Don’t accept marks as the be all and end all. And remember that there are many teachers who are fed up with the whole business of marks too. They realise that marks in themselves don’t mean a thing.16Ibid, 159.

On playgrounds:

Most playgrounds look like car parks or prison exercise yards.

An unwelcoming playground could be made fit for play and relaxation for less than the cost of one teacher’s annual salary. There should be certain basic things in every playground.17Ibid, 155.

No counter-cultural advice is complete without a comment on war:

Outside the schools there organisations like the Air Training Corps and Sea Cadets.

They are meant to teach young people “good military virtues” and hopefully encourage some to join the armed forces when they leave school. Like toy guns and soldiers, war films and so many other things in our society, these organisations reinforce the idea that war is at least necessary, if not actually a good thing. Nobody seems to remember that wars haven’t accomplished anything in the past except killing millions of people, most of them young people.18Ibid, 89.

You may decide that you really do want to be a soldier. Think hard before you commit yourself, though, and remember, whatever the adverts say, when it comes down to it, armies are concerned with killing. You may have to kill other people or get killed yourself, and you don’t get any say in who you’re meant to kill.19Ibid, 177.

On “discrimination against girls” in schools:

Throughout this book we’ve generally referred to both students and teachers as if they were all male. This is only to avoid repeating “he or she” each time. There are of course as many girls as boys at school, and there are almost 50 per cent more female teachers than male teachers.

Unfortunately, many schools seem to think that girls shouldn’t be treated the same as boys. It’s probably true for a start that some girls-only schools don’t attract such good teachers as boys-only schools. And in most co-educational schools it seems to be assumed that the vast majority of girls will become either typists or housewives, or both. While boys can do things like woodwork and engineering[…]

In this respect, schools reflect our society. It is remarkably difficult for a girl to find an interesting job once she leaves school, apart from a few things like nursing which are terribly underpaid anyway. If she looks around, she’ll find there’s very little choice apart from some kind of office work, production-line work in a light engineering factory, being a shop assistant—or starting a family. Boys have much more choice.

If you want to do a subject that girls don’t normally do in your school, just ask the teacher concerned or your head of house…Refuse to be discriminated against because of your sex. This applies after you leave school too.20Ibid, 170.

A final comment on the attitude of adults towards students:

[One argument] against giving students the right to decide things is that they aren’t “mature enough” and “can’t see the real problems”. People have said the same thing about Africans, Eskimos, Red Indians, Chinese, etc. You know yourselves what this argument is worth.21Ibid, 189.

The above is the first article of two on The Little Red Schoolbook. The other article features the second half of the controversial book which contains the notorious passages on sex and drugs

You might also like:

The Little Red Schoolbook: The challenging bits on sex and drugs

Controversial advice on sex and drugs from the schoolchildren’s book

BOOK: THE LITTLE RED SCHOOLBOOK

A Wrinkle in Time: Is it blasphemous or too Christian?

Two reasons Madeleine L’Engle’s book was challenged by religious conservatives

BOOK: A WRINKLE IN TIME

Endnotes