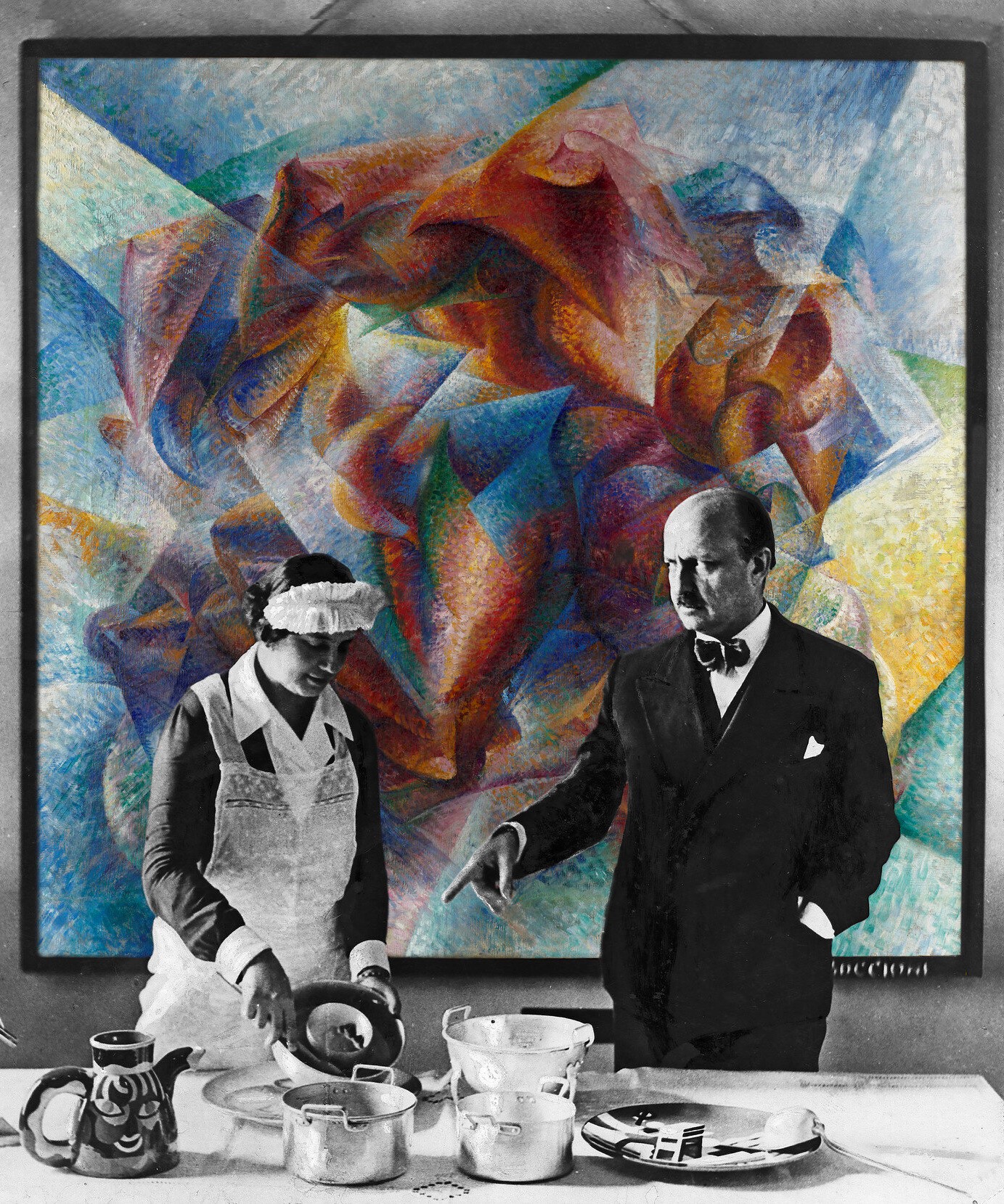

Futurist manifesto: “We wish to glorify war […], and scorn for women”

Futurism was the first movement in the 20th century that aimed to transform life for the masses. Initially, it emerged in art but its proponents brought it to politics and society in Italy and beyond. Avant-garde is French for “advance guard,” and in the context of culture, it refers to progressive, forward-looking, and perhaps radical ideas. Futurism was avant-garde, and its name indicated so. Many fringe groups at the time had proposed solutions regarding “the female question,” demanding more rights and equal treatment. Being a “futuristic” movement, it was expected to be more inclusive of that marginalized group–women–otherwise it would be adhering to the status quo. When the public read the Futurist Manifesto, written by the Italian Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, on the front page of Le Figaro, they were stunned. The ninth point stated:

We wish to glorify war—the sole cleanser of the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive act of the libertarian, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women.1F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 14.

Talking about women and war in one breath

The first few words regarding “glorifying war” were shocking in 1909 as they are today. However, it was the open hostility to women in the last three words (five in the original French, “le mépris de la femme”) that followed its author for years. Criticism prompted him to clarify his position several times. (One wonders how “glorifying war” would have been received, had it been written after World War I.) What is rarely discussed is why a statement on war, militarism and destruction also includes a hostile declaration towards women. A survey of Futurist writings could explain that juxtaposition: Women represented the exact opposite of the hyper-virility, masculinity and strength required by their forward-looking project. The underlying meaning, if we were to speculate, is that women had to be opposed and, perhaps with violence, if just “scorn” does not do the job of pushing them off the path of victory for the Futurist man.

Curiously, over the decades many female fans of Futurism, in addition to some members from the movement which lasted until the mid-1940s, did not think much of that statement and readily presented Marinetti’s own belated explanation which claims that he only wants to destroy the myth of idealized femininity:

We scorn women when conceived as the only ideal, the divine receptacle of love, woman as poison, woman as the tragic plaything, fragile woman, haunting and irresistible, whose voice, weighted down with destiny, and whose dreamlike mane of hair extend into the forest and are continued there in the foliage bathed in moonlight. 2Ibid., 55.

Now that sounds progressive! But is it true?

When admirers of Futurism present this explanation, they also list other reasons on why the founder of Futurism was an advocate of women’s liberation:

1. He supported women’s sexual autonomy, i.e. freedom to have relationships without marriage.

2. He called for the abolition of the traditional family and the release of women from their restrictive gender roles.

3. He supported marriage without legal permission and the facilitation of divorce.

4. Most famously, he supported women’s right to vote and participation in politics, which was a major debate at the time.

5. He supported equal pay between both sexes.

6. He even believed that real equality could happen if women were raised under the right circumstances.

To modern readers, the above might not sound as radical as it was in the early decades of last century. But they were actually issues so controversial that they were fought over by only the most radical of feminists. Could it be that such a man who took the side of feminists was a misogynist? Unfortunately, yes! However, he also took pro-woman positions that even feminists of his era had not been fighting over yet. We’ll examine below each one of the above facts.

“Love is not natural,” “love is fictional”

First let’s examine his post-manifesto explanation. He did express his antagonism towards romantic love, and the “sentimental woman, on many occasions, but other times he denounced “love” without qualifiers. That should not confuse the reader because in mainstream European culture since the 19th century, there is only one kind of heterosexual love—the melodramatic, the “romantic” kind in novels, films and music. “Affectionate” relationships based on arranged marriages, or platonic love barely exist anymore. So he opposed love, period. It’s common knowledge that there’s two aspects that make up love, the emotional and the physical. Feelings and sexual attraction. Well, he detested both! He even broke it all down for us clearly.

“Love is not natural”:

We are convinced that love—sentimentalism and lust—is the least natural thing in the world. Only coitus, the purpose of which is the futurism of species, is natural and important. 3Ibid.

Above, he acknowledges that procreative sex with women is still unavoidable for the propagation of the species.

“Love is fictional”:

Love—romantic obsession and sensual pleasure—is nothing but the invention of poets, who made a present of it to mankind… And poets will retract it as one takes back a manuscript from the hands of a publisher who has shown that he is incapable of publishing it decently. 4Ibid.

He explains here, and rightly so, that if it were not a viable, commercially-successful business, publishers would not work with romantic manuscripts to profit from.

An interviewer once asked him whether he is afraid of infuriating half of the human race because of his “scorn for women.” His response:

We wish to protest against the narrowness of inspiration to which imaginative literature is being increasingly subjected. With noble but all-too-rare exceptions, poems and novels actually seem no longer able to deal with anything other than women and love. It’s an obsessive leitmotif, a depressing literary fixation. Truly, is women the only starting point for, and the only purpose, our intellectual development, the unique driving force of our sensibilities? 5Ibid., 20.

The Futurists saw that stereotype of the sentimental woman as detrimental to both sexes, and as a roadblock to their vision. Marinetti was going against the dominant culture in making such statements. It was a time when Italians were flocking to watch romantic operas by Verdi, Leoncavallo, Mascagni and most famously Puccini. La Bohème (1896), for example, was among one of his time’s most popular operas (listen below to the main character, a poet, serenading a woman and declaring his love under the moonlight).

While he was eager to eradicate love between couples, he still decried the loss of what he described as “absolute love” without giving it a clear definition.

Nowadays women care more for luxuries than for love. A visit to a great dressmaking salon in the company of an obese and gouty banker friend, who pays her bills, is the perfect substitute for the most passionate of love trysts with an adored younger man. The woman finds all the mysteries of love in her choice of an extravagant gown, in the latest fashion, something that her friends do not yet possess. A man cannot love a woman unless she has these luxuries. The lover has lost all status, while Love has lost its absolute value. 6Ibid., 121.

Marinetti: “Love” and “women” are the same—avoid both!

The Futurist visionary’s animosity towards heterosexual love would not be of such critical importance, if he did not consider “love” (sentimentality) and “women” as two sides of the same coin that he’s happy to toss away. The main character of his iconic novel, Mafarka, yelled out during an emotional speech that he’s breaking away from his “impure” past:

Love, women […] I have erased these things from my memory! 7Ibid., 40.

The Futurists believed that women would derail their project. That’s why their ringleader advised his male followers to abstain from even marriage:

[W]e Futurists believe that marriage is a one of the greatest dangers of confronting our exaltation and intellectual freedom.

And this is why we preach the need for celibacy for great men of pure ideas and action. 8Ibid., 71.

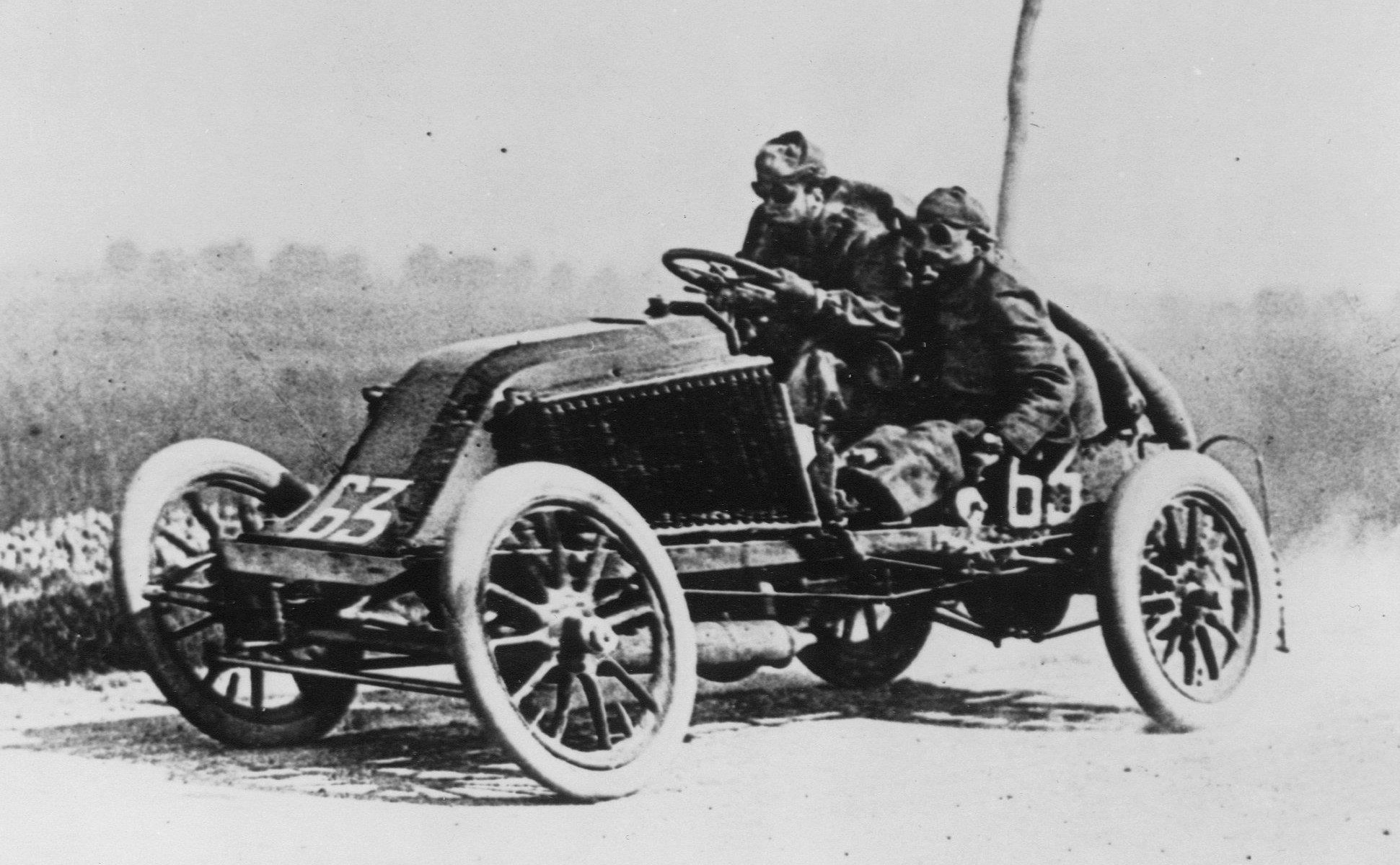

Why does it matter how they felt about women and love? We can not understand the identity of the Futurist unless we see it from the perspective of their contempt towards all things feminine. It was the very definition of the Futurist man. Women, in their eyes, actually the eyes of most men back then, are impulsive and even hysterical at times while men are rational and calculating. Women stood for sentimentality, traditional institutions and ideals, and the past they want to break away from. The Futurist man embodied “virtues” like hyper-masculinity, power and the love of danger. (Marriage will be revisited below.)

Casual sex instead of romantic love

Although the Italian writer, as shown above, railed against women and love, and downplayed the importance of sexual pleasure, he understood that nothing can eliminate the heterosexual desire in men. For that, he recommended, instead of full-fledged relationships, the pursuit of sex as a “merely bodily function”:

The whole enormous business of romantic love is thus reduced to the single purpose of preservation of the species, and physical arousal is at last freed from all that its titillating mystery, from relish for the salacious and from the vanity of Don Juanism; it becomes merely bodily function, like eating and drinking. 9Ibid., 58.

He treated sex as separate from love, long before the hookup culture and its accommodation of “friends with benefits,” “f**k buddies” and “booty calls”:

[Y]oung men of this present age, at long last sick and tired of erotic books, of the twofold drug of sentimentalism and lust, and being at last made immune to the sickness of Love, will have to learn to systematically purge themselves of all heartaches. This they can do through daily eradication of their emotions and seeking endless sexual amusement in rapid, casual encounters with women. 10Ibid., 88.

Fantasizing about procreation without “vulvas”

Mafarka was the ultimate Futurist novel, written by Marinetti and published the same year as the founding manifesto. It included all fundamental themes to the movement: violence, war, glorification of masculinity and technophilia. It is no exaggeration to call it among the most misogynistic novels ever written. Women exist in the narrative largely to serve as victims of rape and sexual assault.

A brutal warlord whose name is Mafarka tells his followers that he’s no longer interested in power but in having a son. So he gives birth, or rather constructs, a superhuman mechanical son, to whom he gives a kiss, breathing life into him. He explains:

[I]t is entirely possible to create an immortal giant with unfailing wings, out of one’s own flesh, without the collaboration and foul-smelling involvement of a woman’s uterus!

[…]

Our will must go out from us so as to take possession of matter and change it according to our whim. […] Soon, if you appeal to your wills, you will too create offspring, without need of any vulva.It is in this way that I have killed love, and in its place I have set the sublime will of heroism! 11Ibid., 38.

Marinetti realizes that he needs female participation for procreation in real life, but in his novel he fantasizes about taking that away from women. He was haunted with the notion that mothers pass “feminine” traits to their male children. Also the narrative of the novel leads one to conclude that he thought the “sacred” gift of procreation is wasted on women and should be seized by men. That happens to directly address one of the reasons that some feminists offer to explain why sexism has been a semi-universal phenomenon. Men, according to this perspective, have a subconscious envy for not being able to bear children like their female partners.

Note that Marinetti is again declaring that without “any vulva,” i.e. women, he would manage to “kill love,” clearly equating both. “Heroism” on the other hand that will replace “love” is masculine and virile, which are the typical qualities in the Futurist man.

The man of the future will be safe from maternal “contamination”

This fantasy of woman-less procreation was also the foundation of Marinetti’s prophetic theory about the “Extended Man,” sometimes translated as the Multiplied Man. He was an early version of a cyborg with transhuman abilities, and whose creation (“multiplication”) does not require human reproduction (a mother). The Futurists imagined man morphing a super machine. British suffrage campaigner, Margaret Nevinson, summarized the outcome of this concoction as:

[A] machine-governed and womanless world in which even the human race may be generated by mechanism, and where everybody will be of masculine gender.

He, who was unabashedly anti-feminine, feminized, and even eroticized, machines

Marinetti was a heterosexual poet who would never write about the beauty of the female body. Meanwhile, throughout his career, he called on men to express their love towards what is truly deserving: “the mechanical beauty”! He spoke about machines with more warmth and appreciation that he ever did about women:

[W]e are promoting the love of the machine—that love we first saw lighting up the faces of engine drivers, scorched and filthy with coal dust though they were. Have you ever watched an engine driver lovingly washing the great powerful body of his engine? He uses the same little acts of tenderness and close familiarity as the lover when caressing his beloved. […] his great, faithful, devoted friend, whose heart was ever giving and courageous, his beautiful engine of steel that had so often glistened sensuously beneath the lubricating caress of his hand? 12Ibid., 85.

He used the same erotic language that he despised in the context of romance, but towards machines.

“Ah yes! you, little machine gun, are a fascinating woman, and sinister, and divine, at the driving wheel of an invisible hundred horsepower, roaring and exploding with impatience.” (Inventing Futurism)

The hyper-masculine misogynistic writings of Futurists is a fertile field for psychoanalytic exploration. Why they preferred machines over women? Perhaps because machines silently take and follow instructions. Or because they are powerful, cold and undemanding. Whatever it is that “the machine” had, woman lacked. Professor of fine arts, Christine Poggi says of the Futurist man:

“The machine [plays] the parts of feminized lover, daughter, and phallic prosthesis all at once.”

In the Futurist world, women would ideally become more like men and rise above sentimentality and the desire for reproduction. Simultaneously, both sexes would repress their sexual instincts. In that sense, Marinetti envisions humans becoming more like the “divine” machines he admired throughout his life.

Marinetti: Male homosexuality for the youth cements “camaraderie”

He endorsed homosexuality for young men as a ritual of bonding during a phase which should end by the age of thirty. In a lecture in London after the famous writer Oscar Wilde was convicted of homosexuality, he exhorted his “hypocritical” English audience:

So far as your young men of twenty are concerned, nearly all of them, at some time or other, are homosexual. This perfectly respectable preference of theirs stems from some sort of intensification of camaraderie and friendship, in the realm of athletic sports, before they reach the age of thirty—that age of work and order in which they suddenly return from Sodom to become engaged to some impudent young hussy. 13Ibid., 91.

“Dangerous” mixing of boys and girls in the playground

He urged the segregation of boys from girls at a young age. It was also a promise on his political agenda based on the movement:

[T]hat mixing of males with females at a very early age, which is the cause of a harmful effeminacy in the male, will be abolished once and for all.

Male children—in our opinion—must develop separately from little girls, so that their early games are unequivocally masculine, which is to say, totally devoid of all cloying affections, of all womanish refinements. They must be lively, combative, muscular, and violently dynamic. 14Ibid., 311.

Marinetti: Little boys are best brought up without maternal care

To completely eradicate feminine characteristics transferred across generations, based on his understanding, he hoped to abolish maternal care, and replace it with “state care.” In fact, he found the often-mocked, stereotypical care of Italian mothers to be detrimental to the Futurist project:

[W]hile Italian women—who are utterly inferior to the women of Germanic origins—are delightful dispensers of passionate caresses, they are absolutely incapable of understanding and supporting a man engaged in heroic, unselfish struggle.

Italian women, though the sweetest of mothers, cultivate cowardice in their sons, when they aren’t simply dominated by priests or by the constant desire for excessive luxuries—they become almost invincible enemies and an insurmountable barrier, in all the great conflagrations of war and revolution. 15Ibid., 70.

He had no use for the gentle nature of mothers:

If the family works well, it is a quagmire of sentimentalism, a gravestone of maternal care. 16Ibid., 310.

Marinetti: Release women from the shackles of marriage, and abolish the traditional family

Real aim: Futurist men are better off without marriage—”free women” are available for casual sex

In another manifesto for the Futurist political party, Marinetti denounced the traditional family and declared that he’ll work to subvert it. His political reforms were to include:

Abolition of marital permission. Easy divorce. Gradual devaluation of marriage, eventually to be replaced by free love and children reared in State institutions. 17Ibid., 272.

It’s hard to imagine how radical the above statement was for its time. It contains 5 ideas, all of which were highly controversial. To overthrow the institution of marriage, he proposes the abolition of the marital license, easy divorce and easy sex. In his view, marriage is based on decadent bourgeois morality:

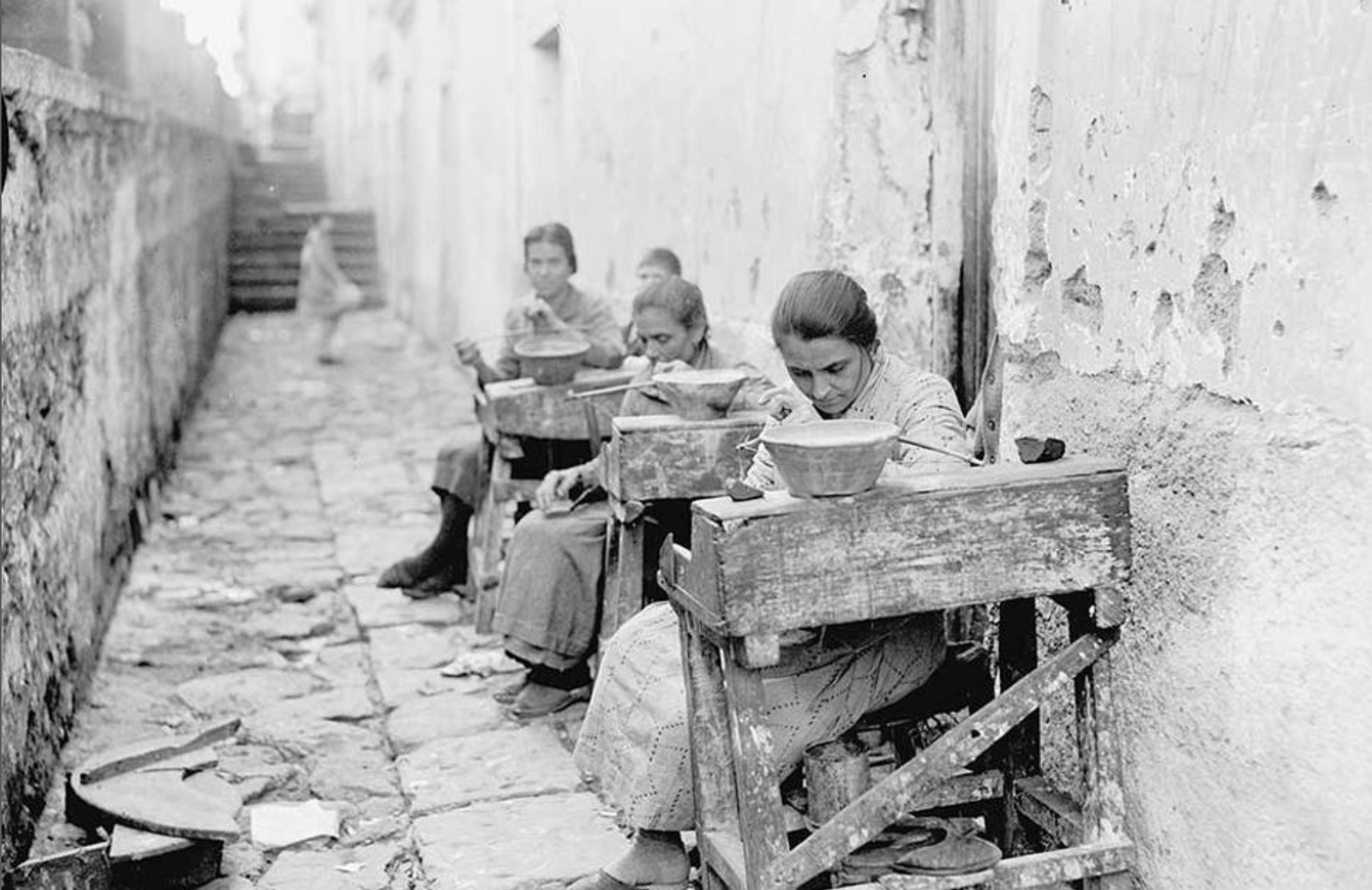

The family which, so far as the woman is concerned is born out of a buying and selling of body and soul becomes a masquerade of hypocrisies or else a facade of good sense, behind which a legalized prostitution, with a dusting of moralism, is played out. 18Ibid., 310.

He used harsh words to denounce marriage–”legalized prostitution”–where economic incentives, not love, pulls the invisible strings. That is not untrue considering that the majority of women were still unable to work, but they had to rely on a husband, or their own fathers, to simply survive. He saw the family structure as an impediment that stunts the personal growth of all its members. Also the trivial day-to-day affairs of the family competes with greater projects, like Futurism. Thus, the actualization of the Futurist dream could never happen unless family members are freed from their conventional roles.

Once the traditional family dissolves, young women would no longer have to “hunt for a husband.” That is a custom he finds particularly contemptible and it’s easy to see why when the prey is “man” who should be on a more important mission in life!

The abject hunt for a husband will finally be abolished, along with the ridiculous ordeal of frantic mothers who bring their eligible daughters up to every ball or to seaside resorts, like so many heavy crosses, to be driven into the ludicrous Golgotha of a good marriage. 19Ibid., 311.

Even though he had a vision for a future without “the family,” he was not sure what would take its place:

[I]f the family, which stifles all vital energies, is to disappear, then we’ll have to try and get along without it. 20Ibid., 58.

Among the most powerful statements by the Futurist founder regarding women’s rights is one where he explicitly calls for women’s emancipation from the patriarchal system. It’s quite a feminist stance, but at a closer look, it is still problematic:

We want to destroy not only the ownership of the land but also that of women. Those who do not know how to work the land should be dispossessed of it. Those who cannot give joy and strength to women should not impose their embrace or their presence upon them.

Woman does not belong to man but rather to the future and to the development of the human race.

We want a woman to love a man and to give herself to him only for as long as she wishes. 21Ibid., 310.

In the Futurist worldview, women should not become members of a family, rather attain the status of a national asset belonging “to the future and to the development of the human race.” He failed to provide details on what exactly that entails but clearly she is not as autonomous as it might seem at first glance.

Marinetti’s support for women’s rights was strategic, with the Futurist man in mind. Without the family or sentimental relationships, he could achieve greatness. He is better off celibate but if not possible, he could still enjoy “rapid casual encounters.” Another hidden benefit he found in the dissolution of the traditional family is boys growing up without “feminizing” maternal care as mentioned above. The State could take over that role.

Marinetti: Women should acquire the right to vote and participate in politics

Real aim: Women’s vote will hasten the collapse of parliamentarianism which Futurists oppose

The most blatant and infamous example of ulterior reasons behind the Futurist ringleader’s support for women was his advocacy of their right to vote.

[T]he suffragettes are our best allies in that the more rights and powers they can secure for women, the more will their urge to love be impoverished, to such an extent that they will cease to be the focal point of sentimental passion or of lust.

[…]What is certain, however, is that in her present state of servitude, both intellectual and erotic, woman, finding herself in an absolute state of inferiority from the point of view of intelligence and character, can only be a mediocre legislative instrument. 22Ibid., 56.

Marinetti considers love and sentimentality (and women) distractions to men. So by giving women more rights, like the right to vote, both sexes will benefit. Women would be less susceptible to be stricken by “the sickness of Love,” as he called it. However Marinetti finds Women, like most men of his generation, emotional and irrational by nature, which means politicians could easily manipulate them. Women’s “intellectual inferiority,” which Marinetti is referring to, is probably his way of clandestinely taking the anti-woman side of the debate, that is when less than a quarter of Italian women are uneducated, or rather denied the right of education, they could not possibly understand politics and vote. It was not a position without a merit. (To this day, we place great importance on voters being educated, or well-informed, since their input contributes to the entire democratic process.) He sees women as useful “instrument,” i.e. they should be encouraged to contaminate the political system to expedite its collapse and dismantle parliamentarianism.

Let women, swift as lightning, hurry to make this great experiment in the total animalization of politics.

We who deeply despise politics are happy to abandon parliamentarianism to the spiteful claws of women; for it is precisely to them that the noble task of killing it for good has been reserved. (Source: Modernism: An Anthology)

You’ll catch a whiff of hypocrisy here! He’s ready to denigrate politicians for potentially manipulating women, yet he, himself, wants to use them for political purposes! Note also how Marinetti who publicly rejected outdated portrayal of women is using old dehumanizing vocabulary to describe them: they would bring “total animalization of politics” and in whose “spiteful claws” the political order will collapse. That is the familiar image of the over-sexualized femme fatale since the Greek myths until modern times. They were, and still are, portrayed as sirens, mermaids, serpents, bitches and cougars.

In other articles, he was more forthright on this issue. He registered his concern that women are inherently passive, and their traits are the exact opposite of those in the war-glorifying, Futurist men, hence their involvement in governance is an unwelcome progress:

It is very apparent that a government composed of women or one supported by women would drag us fatally down the road of pacifism and Tolstoyan cowardice. 23Ibid., 57.

Marinetti’s support for working women: They should have equal pay to men

Marinetti elsewhere: Work is for men–women who choose to work should earn less than men

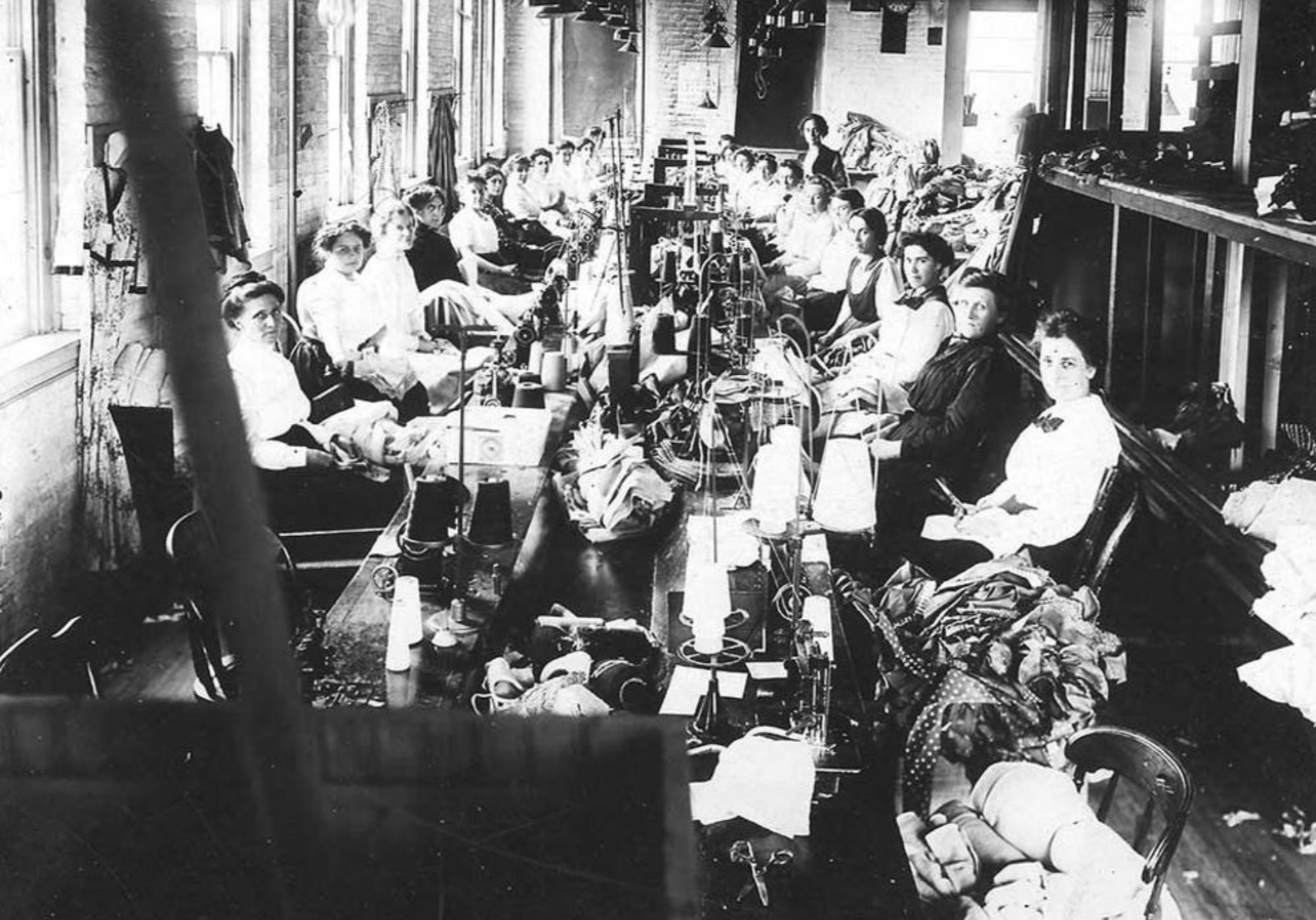

He never publicly opposed women’s right to work and he never endorsed it either. To him, it was the reality after World War I when women had to enter the workforce to make up for the shortage left behind as men were on the front-lines. Even after the soldiers returned home, many were physically or psychologically too damaged to re-enter the workforce.

In 1918, on the platform of the Futurist Political Party he founded, he endorsed women’s work and even called for…

Parity of remuneration for men and women for equal work. 24Ibid., 273.

However, the following year, 1919, he condemned women who were joining the workforce during the war and considered it threatening to the unity of the family particularly when a working woman earns more than her man:

The widespread participation of women in the national labor force, brought about by the way, has created a typical piece of matrimonial grotesquerie. The husband used to hold the money or used to earn it, but now he has lost it and is struggling to start earning it again.

His wife works and finds the means of earning a substantial wage at a time when the cost of living is very high.

The wife, because of that selfsame job, has no need to be a housewife, while her husband, not having a job, concentrates all his energies on an absurd concern with domestic order.

The complete overturning of the family, in which the husband has become a useless woman, with bullying masculine ways, and the wife has doubled her human and social value.

An inevitable clash between the two partners, conflict and the defeat of the male. 25Ibid., 311.

Although, he never explicitly called for women to be denied the right to work, he clearly found it problematic in many cases, and perhaps even threatening to male identity. It’s hard to reconcile the above paragraph, repeating the 19th century position on traditional roles within the family, with his career-long message on emancipating women from their inferior status.

Marinetti: Women and men could achieve equality in the future under the right circumstances

Marinetti meant to say: Women and men are not and can not be equal now

A shallow dive into Futurism, particularly its progressive statements on women’s emancipation, might mislead the reader into thinking that Marinetti called for equality between the sexes. He never did! Equality is not possible, he declared, for the time being, though attainable if women received proper education in the future:

So far as the claimed inferiority of woman is concerned, we think that if her body and spirit had experienced an upbringing identical to that of the spirit and body of man, over very many generations, it might perhaps have been possible to speak of equality between the two sexes. 26Ibid., 56.

What the Futurist founder thought of Feminism

Unsurprisingly, the movement that glorified man and all things masculine was opposed to feminism. The tenth point on the Futurist Manifesto was:

We wish to […] fight against moralism, feminism, and every kind of materialistic, self-serving cowardice. 27Ibid., 14.

In his typical manipulative fashion, Marinetti looked forward to feminist victory to eagerly bring down institutions of the past, be it political or cultural:

[T]he victory of feminism, and particularly the influence of women in politics, will end up destroying the family principle. 28Ibid., 58.

Ironically, the press sometimes equated the two avant-garde movements, feminism and Futurism, without seeing much of a difference, and denigrated both of them together.

Did Marinetti’s talk about women’s autonomy lead to any progress?

The support he offered the women’s movement was only verbal and strategic as demonstrated. In fact, during the Fascist era, he accepted all policies, including those that conflicted with his own regarding women. The Fascist government, from 1922 to 1943, enforced values of the Roman Catholic Church. Their teachings were women’s maternal role is sacred and they belong to the private sphere of home, epitomized in the infamous Nazi catchphrase Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen, church).

Futurism preceded Fascism in Italy by a decade and it provided the philosophical basis for many of its ideas on violence, war and nationalism. One can’t help but wonder how history would have judged Fascism, had they inherited the entire Futurist package including their stance towards women’s liberation, however contradictory.

No place for women in the Futurist vision

So if women were to be “relieved” from their traditional roles as lovers, wives, and somehow, as mothers, assuming they’re no longer relevant to procreation, what would their role be according to the Futurist vision? No answer provided. If there was too much left unsaid about women in the Futurist world, it’s probably due to the fact they had no model for such an independent, “unemotional” woman, the kind they dreamt of. If for generations the image of women were associated with sentimentality, then it becomes obvious why if they discard one, they discard the other. That is why women, as they knew them, don’t seem to have a place, or a role to play, in their Futuristic vision.

Looking back, it’s tempting to judge harshly the statements made by historical figures on complicated cultural issues. The “female question” had been challenging thinkers and writers for generations throughout the 19th century. New ideas take time to develop and even when they do, they’re often met with resistance. That explains why many of the historical figures who tackled the issue of women’s liberation were hesitant, conflicted, hypocritical or simply cowardly.

In hindsight, were his views on women reactionary or revolutionary?

His overall views defy easy categorization. Perhaps “reactionary futurist” is the label that best fits him, considering the contradictions and inconsistencies in his writings. He was anti-marriage, yet he got married later in life. He preached the destruction of academies but became a member of a conservative Italian academy in 1928. He was anti-Catholic but he turned to Catholicism in the last decade of his life. The founder of Futurism is likely the only historical figure one might encounter who was misogynist, yet paradoxically held several proto-feminist positions, i.e. ideas that were yet to become hot feminist issues in the 20th century.

Generally, the founder of Futurism was far more supportive of women’s liberation than his contemporaries. Some of his progressive ideas, you might say, had the interest of man at heart. That is true! However, he deserves recognition for denouncing hypocritical bourgeois morality and for challenging the centuries-old European institutions, like marriage and the traditional family. Marinetti was boldly throwing his support behind women’s independence, sexual freedom and easy divorce at a time in Italy where women were denied the right to engage in trade, manage property or hold an official post, unless there’s an authorization from a husband or a father. The Futurist political promise of legalizing divorce was fulfilled in Italy six decades later, in 1970!

He bravely stated that the male dominated culture subjugate women and that wives should not be subservient. The very fact that he sincerely called for women’s autonomy and the end of their treatment as men’s property was courageous. Before it became a common idea, he considered women’s gender role an oppressive cultural construct and he believed that they could and should escape it. He believed that women could be nurtured to be equal to men–another radical idea for its time. Long before it became mainstream, his writings disentangled love and sex in relationships. He went even further and considered monogamy archaic while advocating free love.

Looking beyond his antagonistic attitude to women and obsessive fear from femininity, we’ll find that he did believe that women are capable of a more active role in modern society. Above all, he believed that there’s hope for equality between the sexes in the future. And as such, the label “misogynist” to his name shall forever have an asterisk next to it.

You might also like:

Italian Futurists: The first to love and worship the machine

The machine demonized, deified, humanized and eventually merged with us

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Futurists vs Romantics: Extreme views on technology and nature

Gazing at the stars, from Goethe, Marinetti to Google Sky

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Endnotes