Edna, the main character of Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, is a typical wife-mother who loves her children. She experiences an inner conflict that prompts her to find an independent existence from her domestic role. At the final scene of the book, when she finds out that she could never escape her self-sacrificial obligation towards her children, she commits suicide. A 21st-century reader might wonder what makes a loving mother feel hopelessly enslaved by her children? A historical overview of women’s subjugation through motherhood could put that act in perspective.

1. Marriage as a family transaction

For millennia, if you were a woman, a new phase of life started shortly after puberty between the ages of 15 and 19 when your father handed you over to another man to be your husband. That’s a transaction which certainly doesn’t involve chocolate, roses or scented candles. You approach your wedding night with anxiety because you have almost no knowledge about what to expect during the consummation. A chaste girl was never expected to know much about sex.

2. A fucking machine: “no sexual feelings”

The wedding night marks the beginning of a life devoted to childbearing and breastfeeding. Wifehood and motherhood — that is, sex and procreation — define you as a member in the family and the community. British doctor William Acton (1813–1875) assures us that “the majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled with sexual feeling of any kind.” He explains that surely, nymphomaniacs do exist and we could find them at “lunatic asylums,” but they are the exception. Those “low, vulgar women” that young men might want to take to bed are different from the chaste ones who they eventually marry and whose “sexual feelings” are inactive. “[A] modest woman seldom desires any sexual gratification for herself. She submits to her husband, but only to please him; and, but for the desire of maternity, would far rather be relieved from his attentions.” He also tells us that the best women “know little or nothing of sexual indulgences. Love of home, children, and domestic duties are the only passions they feel.” 1Steven Marcus, The Other Victorians: A Study of Sexuality and Pornography in Mid-Nineteenth Century England (New York: Basic Books, 1966; reprint, New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2009), 31.

While history shows that mothers were often marginalized and voiceless, they were still held up against unique, glorified standards. In the West, they were supposed to follow the impossible-to-attain example of the virgin-mother Mary. The ideal of virginal motherhood was not only self-contradictory but also promoted a mostly sexless marital life, with procreation at its center. That spiritual ideal did not leave women much room for normal sexuality in marriage or other aspirations beyond childbearing.

Is there (or was there) any truth to women lacking sexual desire? Historical context could help answer this question: If you were a 19-year old woman who had been religiously and culturally indoctrinated all her life that sex is inherently dirty but necessary for procreation, you knew very little about your own body and even less about the male anatomy, and sex was that mysterious act that likely resulted in a life-threatening and excruciating childbirth, would you still be excited about it? If you knew you’re under a marital obligation to be constantly available to your husband’s desires regardless of how you feel, and that his pleasure was the main objective, so much so that his climax brings an end the intercourse, would you still be excited about it? A popular Victorian-era word of advice to young women, being approached for sex by their husbands was to “close your eyes and think of England.” (How about that for “sex education”?) That advice reveals that not only is your consent irrelevant, but also you owe it to your husband and to your country that you sexually submit without hesitation for the duty of bearing children.

3. A breeding machine for, preferably, boys

As you age, you feel proud for having taking part in the honor of “making men.” In wartime, you’re praised as an incubator of heroes. The image of motherhood changed little but its essence stayed the same across different periods and cultures. An American doctor in the early 1900s was behind a well-known phrase that summed it up: the only way to make a woman happy is to keep her barefoot and pregnant in the kitchen. The Nazi era, reused a phrase from the German Empire days, Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen, church).

Numbers are hard to come by, but in your short lifespan which was around half of ours today until the 19th century, the total number of babies you delivered was often closer to a dozen than a half dozen. Although this article focuses on Western countries, many facts apply globally. If you were a mother in Egypt in the early centuries of the first millennium, you’d have 8 or 9 babies. You’d still produce the same number (“8.7 on average”)2Gregory Clark, “Chapter 4: Fertility in the Malthusian Era” (research paper, University of California, Davis, 2003), 3. This document can be found at: http://faculty.econ.ucdavis.edu/faculty/gclark/papers/book2003-4.doc if you were a French mother in the 17th century. That’s all assuming you actually survive the childbirths.

The fortunate mother do not only survive the childbirth but also deliver boys. Boys carry fathers’ last names in the almost universal tradition called patrilineal succession. The father’s lineage (and, in a sense, his quest for immortality) is at risk if you’re “cursed” with only girls, in which case, the father could move on to find another potential mother.

4. The shame of being “barren”

Historically, you belonged to one of three groups, “potential mothers, current mothers or failed mothers.”3Caitlin Holmes, “The Social Construction of Motherhood” (master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, 2006), 15. The latter lived in shame. In a Christian society, as in a Jewish or Muslim one, children were seen literally as divine blessings, therefore there had to be reason for God to will that you be infertile. In absence of modern understanding of fertility, unless the husband visibly suffers from impotence (erectile dysfunction), the burden of infertility was always on women. One way to atone for this disgrace was by looking after other people’s children.

Modern science shows that a normal male sexual performance doesn’t rule out the possibility of infertility due to low sperm count or sperm transport disorders. But wives and even physicians were usually hesitant to assume male responsibility. A wife who does so might shatter her man’s fragile ego and put herself at the risk of mistreatment, or worse, beatings or abandonment. The inability to conceive in our times is no longer treated like a divine punishment or a magical spell, but a medical problem with possible solutions.

Voluntary childlessness: When Woman’s supreme contribution was the production of babies, choosing to have no children or to postpone it was never on the proverbial table. A child-free lifestyle or “let’s just take time to enjoy each other first” were unheard of.

5. Childbirth under the shadow of death

Christianity, like Judaism before it, taught that childbirth pain was women’s “lot in life.” In Genesis 3, God pronounced Eve’s punishment for her sin: In sorrow thou shalt bring forth children. (Adam somehow negotiated a lighter punishment for his own body: a bump on his larynx.) However, pain, the extreme kind, was not Eve’s biggest fear. She always worried more about her impending encounter with death in case of complications.

The ordeal of childbirth was the main reason that women’s life expectancy was lower than men’s. Before the advent of science, your demise could be the result of prolonged labor due to a fetal malpresentation (abnormal position), postpartum hemorrhage, or just an infection. Infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and pneumonia were major killers of mothers and infants. A British mother in 2015 had 1-in-7000 (0.014%) chance of dying during childbirth, but in medieval times her chances were 1-in-10 (“10 percent“). If you weren’t confident you’ll survive, it was not unusual that you tell your family of your preferred name for the newborn. Some pregnant women in more recent times, specifically the 18th and 19th centuries, would even write a will in advance of labor. Your mind at childbirth could possibly be preoccupied with who’ll look after your motherless infant or your other children if you didn’t survive. The extended family was always ready in case of a tragic outcome.

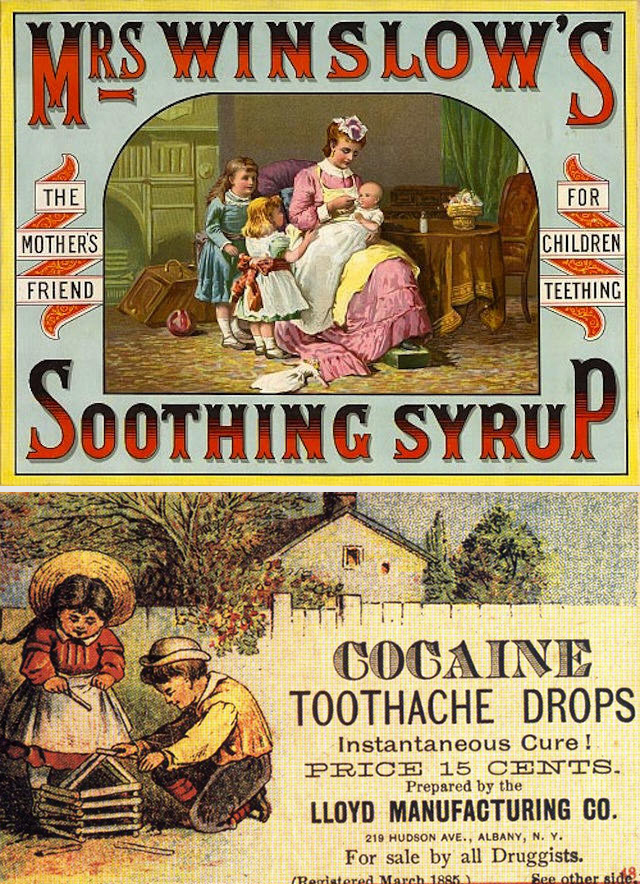

If you notice signs of labor, an elder female family member or acquaintance turns up to act as the mid-wife. During and after the pregnancy, homemade remedies were available. There was never a shortage in quackery and snake oil-type healers, and the recipes ranged from ineffective to dangerous.

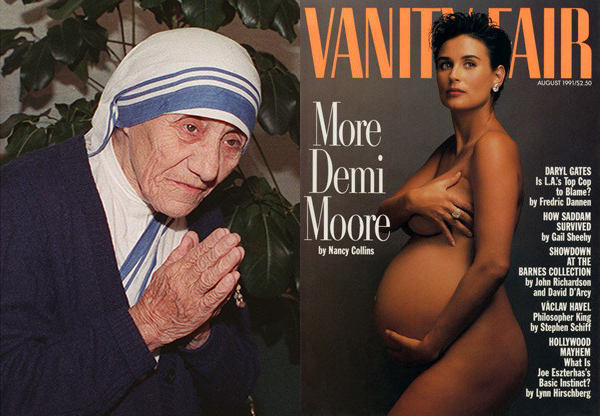

However, in the 19th century, physicians (mostly male) became available to upper and middle class women who lived in urban areas, and were experiencing complicated deliveries. Goodness knows how many women in the early days were victims of narrow-minded husbands who couldn’t be seen allowing male strangers (that is, physicians) into their homes. It would take decades before this practice becomes widely acceptable. Looking back, that was the Victorian period when it was too crude to even explicitly mention “pregnancy,” because it carried a clear implication of sex. They used euphemisms like “with child,” “in the family way,” and another one which we still use, “expecting.” “Confinement” is another sad euphemism, because it meant just that – out of public sight until the child is born.

In the 1800s, the public welcomed experiments with pain relief for childbirth. Although some religious leaders opposed this medical intervention, most clergy and laypeople couldn’t wait for an end to the childbirth suffering. If you were a middle-class member and able to summon a physician to your home, you would have been administered chloroform, opium, laudanum (essentially opium in alcohol), ergot (a fungus used to induce labor, sometimes known as nature’s LSD) or some other drug you’ve never heard of. Clearly, these forms of anesthesia came with problems, like stopping contractions and other risks to the baby. Even though the mother and fetus don’t share the same bloodstream, nutrients and drugs still cross through the placenta, meaning this experimentation resulted in drugged-up newborns and a fresh list of health risks to deal with. As for the mother, she would be unconscious while the baby is being delivered. When she wakes, she’d have no awareness of the life-changing experience.

By 1915, anesthetics which regrettably knocked out women during birthing were replaced by “twilight sleep,” a method which was celebrated by doctors and demanded by women. The drug was a combination of morphine (for pain relief) and scopolamine (for, basically, memory erasure of the event), resulting in semi-conscious state of partial analgesia and amnesia. Partial analgesia does not mean you don’t feel horrendous pain, you just, thanks to scopolamine, don’t remember any of it, and that includes the birthing itself.

If you do survive the childbirth, there was a relatively high chance that your child won’t survive the early days or weeks of infancy. As many as half of the infants from the preceding period to ancient civilizations did not survive. If you were a mother from the Roman era4David Soren and Noelle Soren, A Roman Villa and a Late Roman Infant Cemetery (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1999), 482., or the Middle Ages5Roberta Gilchrist, Medieval Life: Archaeology and the Life Course (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2012), 46., your infant would have had around 30% chance of dying.

Many husbands turned to prostitutes to fulfill their sexual needs while their wives were too busy with their infants. That was tragically ironic because many women who happen to survive childbirth, were infected and killed by venereal diseases brought home by cheating husbands.

Beyond infectious diseases, contaminated cow milk was a major killer for the infants to whom breastfeeding was not available. Also, popular drugs of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century didn’t help with infant mortality. Mothers followed the common advice and spoon-fed restless infants and children narcotics such as opium-based laudanum. The famous morphine-based Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup and cocaine lozenges were administered for teething pain, asthma, coughs, colds and bronchitis. All it took to kill an infant was an overdose. Another problem, as one doctor stated, was starvation because a coked up baby won’t cry to alert you it needs milk.

Also C-section (Caesarean) delivery, which had been around for many centuries, was a gamble that often resulted in the death of the mother or the child. Only in the 19th century, it became safer. Today it’s such a routine procedure that 32% of American mothers used it in 2016.

Scientific salvation in the form of antibiotics and blood banks would arrive only in the 20th century ushering in the first period in history when mothers didn’t face the fear of death while birthing. With antibiotics, immunizations, sterilization and other medical breakthroughs, the heart-wrenching but all too common image of a mother’s agony over a little casket was finally fading.

But the early days of medicalized childbirth were not free from risks. You could have been among the unfortunate ones, on whom some inexperienced, young doctor tested his dubious remedies, or perhaps misused his metal instruments (forceps) and injured your child during the delivery. With such dangers, traditional mid-wives of the 19th century had reasons to scoff at that new approach that began to marginalize them. It was largely an experimental period that lasted for a full century but it introduced professionals like gynecologists, obstetricians, anesthetists and other health care professionals we rely on. Today’s highly-skilled, educated midwives bear little resemblance in knowledge or experience to their counterparts of the past. Also, today you could work out a birth plan and post-delivery birth care, have less drugs pushed into your bloodstream and you’re almost always awake during the delivery.

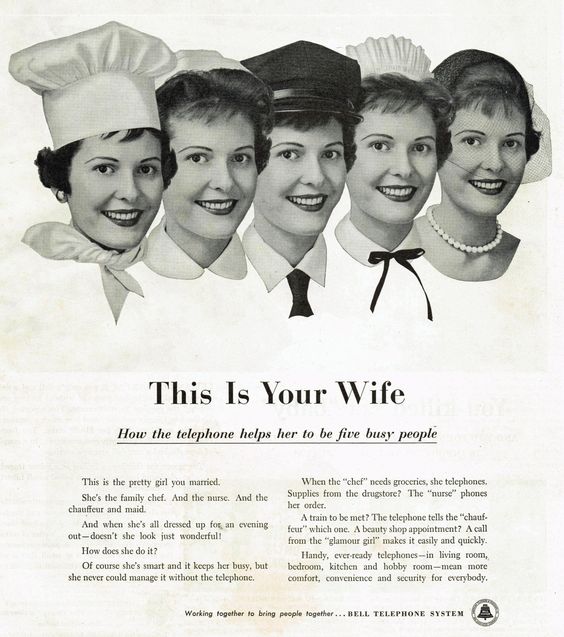

6. The domestic zone: Know your place!

Though women have always been responsible for the management of home, it was during the 18th and 19th centuries that this duty was transformed into an idealized system of rules, routines and expectations. Historians call it the Cult of Domesticity or True Womanhood. Men and women of upper and middle class believed they belong to separate spheres, yet their roles complement each other. The harsh world of the public sphere is for men, and that’s where they need to be to earn a living. The private sphere is where women should be to provide men a refuge from the public sphere, and also to care for their children. Women were expected to ensure all domestic tasks are carried out including cooking, cleaning and decorating. Unlike men who possess “greater reason,” women were considered more emotional and best suited to be moral guardians and spiritual disciplinarians for children in the domestic zone. A wife and mother was expected to be, and seen as, “the angel in the house.”

This sentimentalized image of women was common beyond Great Britain. French philosopher, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), had something to say about the domestic sphere: “the empire of woman is an empire of softness, of address, of complacency; her commands are caresses, her menaces are tears 6Alexander Walker, Woman Physiologically Considered, as to Mind, Morals, Marriage, Matrimonial Slavery, Infidelity and Divorce (New York: J. & H. G. Langley, 1840; Charleston, SC: Forgotten Books, 2017) 133. For the French original, see Rousseau, Emile ou De l’éducation: L’empire de la femme est un empire de douceur, d’addresse, et de complaisance; ses ordres sont des caresses, ses menaces sont des pleurs.. In 1865, an American poet, William Ross Wallace, wrote his best-known line: “The hand that rocks the cradle is the hand that rules the world”. But that value system was not for everyone; for the ladies of society only. African American, immigrant and even white working class women were exempted. Such a rigid gender distinction as an ideal lasted for more than a century. Mass culture constantly reminded women to “know their place,” with not-so-subtle messages in 19th century magazines and all the way into 1950s TV shows.

American mothers after the revolution were described in political terms. From the 1780s, they were entrusted with what a historian called “Republican Motherhood.” Virtues of the nascent Republic like patriotism and piety were to be passed on by mothers to their children. While they were not legally separate from their husbands (i.e. not citizens) or able to vote, they were glorified and told they’re responsible for upholding the values on which the nation would rise.

At one end was the glorification of mothers, at the other was their blame for a host of social ills such as the high rates of juvenile delinquency, the unruly street children and even homosexuality (considered a problem at the time). They were blamed for producing too many children, not enough children, not enough males; for being too close to them, too distant or too strict.

Men who were opposed to women competing with them in the workplace urged others to preserve the ideal of separate spheres. The myth they spread was that women traditionally never worked, except those who belonged to the very bottom of society — servants or prostitutes. Although that claim was tragically true due to their extreme poverty, the bigger picture was more complex: In agrarian societies, most women took part in the back-breaking farm work. Also, in the industrial era, middle-class women worked, albeit at lower wages and for only a limited set of professions. There were school teachers, innkeepers and shop keepers. Others worked at home as dress makers and seamstresses. Even in the 1950s — the decade that is depicted as one where wives never left the domestic domain — women were able to join the workforce while their children were at school.

Life for women in the private sphere was not as luxurious as often imagined. Housework was a daily challenge before appliances like refrigerators, washing machines, dishwashers, or the simple invention of disposable diapers. Without refrigeration, for example, you’d have to cook on almost a daily basis. Preservation of food is not easy to maintain specially in the summer heat. Even indoor plumbing is a luxury they didn’t have. Fountains that serve as tourist attractions today were spots for women to either fill up their buckets with water (imagine the walk home!) or wash their laundry. Regardless of the circumstances, men never took part in the household chores. Some of the chores were shared among the women of the community, particularly in villages. Only when women joined the labor force in droves in the 1960s did men realize that they had to share the housework and childcare. Since then, most husbands who are uncooperative find themselves invoking a backlash that end peacefully with “we’ll have a takeout for dinner tonight” or, in extreme cases, divorce.

7. Today we call it marital rape

Refusing to sexually submit to your husband, to whom you “belong,” was often met with force. That act was interpreted as man exercising his marital right. Your husband is expecting you to occasionally say “no” because your sexual drive is supposedly much weaker than his. Only a prostitute would flaunt her sexual passion and take charge in the bedroom. Up to the 1800s, that view did not only prevail, but was perpetuated by scientists and scholars. With such views towards female nature, it becomes a woman’s obligation to submit to her husband’s rape or alternatively his duty to force himself onto her.

Accusing your husband of rape in any community with a police force in the 19th century would have not been taken seriously. But it was during that period that the idea of consensual sex within marriage started to develop. It was criminalized around the world only in the 20th century.

8. Abusive relationships: Without my husband who’ll feed us?

Long before 20th-century social programs and government assistance, many women’s economic security tragically depended on cooking food and meeting men’s sexual desires. Women had to stay in abusive marriages because they couldn’t otherwise survive economically, and also because they knew that if they walk away, and some did, they might never see their children again. If your husband does abandon you, or you become widowed or “deserted” (separated), the prospect of you and your children literally starving on the streets or scavenging for food is real. That is the same threat looming over a woman who couldn’t get a man to marry her. Fathers had full custody of the children if the marriage dissolved, effectively stripping mothers from any rights towards them. However, from the 1800s, the rare outcome of divorce was handled differently: Some courts began to see children as innocent beings in need of emotional support, rather than miniature adults or economic assets ripe for industrial exploitation. That point of view made mothers best suited for the custody of children.

Your husband normally wouldn’t reveal to you how much he earns, or you wouldn’t dare ask, but he’d still give you an allowance regularly for the expenses of the home. How much allowance is necessary to feed and clothe a family was a source of never-ending tension between couples. Some mothers’ misfortune was that their husbands would waste their wages on drinking or gambling while they’re impoverished at home. Some men went even further by asking their working wives to hand over their wages to them. This was more than the ordinary mistreatment: It was a bitter (and sometimes violent) reaction from many working class men towards their wives’ work. The fact that they fail to provide for their wives and children was a blow to their masculinity.

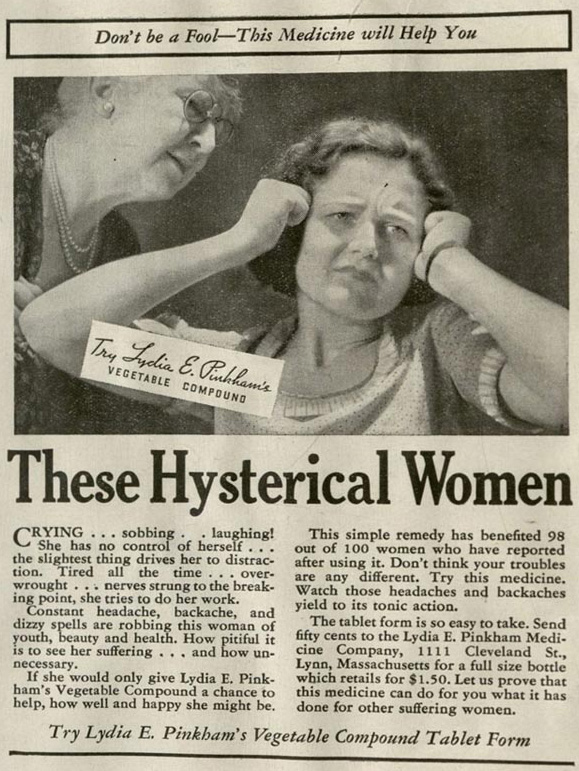

“The weaker sex,” “the fair sex,” and “the gentle sex” were all humiliating references to women. Seeing them as unstable required that they follow different behavioral rules. The male-dominated establishment of medicine played a negative role here too. What they diagnosed as “female hysteria” was a catch-all term from the pre-psychiatric period to describe everything between a strong emotional reaction to real mental illness. An absurd manifestation of such rules was specifically directed at pregnant women who had to avoid getting angry, sexually aroused or working mentally for a few hours. For some men, this created room to manipulate women at their most vulnerable and a way to incapacitate them from behaving normally — Why you’re angry?! It’s not good for our baby!

9. Wife beating: When it was a man’s duty to discipline his wife

Within the confines of home, physical punishment was always generously delivered to wives ― neither children nor servants were spared. That mistreatment of women across history fosters the rage of radical feminists like Marilyn French. Although she was accused of being a man-hater, it’s hard to explain away issues of this kind which she raised in her book, From Eve to Dawn, A History of Women in the World, Volume III in a 19th century context:

It was generally believed that men had the right to beat wives, but women sometimes left men because of violence, or because men threatened to murder them or attacked their children… One woman told a police court missionary, “I would forgive anything but the filthy names he calls me.” She was indeed forgiving: at twenty-three, she was deaf in one ear and had a broken nose from her husband’s fists… Male violence to women pervaded working-class society.7Marilyn French, From Eve to Dawn, A History of Women in the World, Volume III: Infernos and Paradises, The Triumph of Capitalism in the 19th Century (New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York), 82.

The vicious beatings were often made worse by drunkenness. Elsewhere in her book, French regrets that not until the 20th century was domestic violence acknowledged as a problem and was eventually criminalized.

10. Education is bad for your ovaries!

From the late 1700s and into the early 1800s, opponents of female education claimed that women lacked the mental capacity for high-level thinking. The dominant pseudo-scientific theories of phrenology provided evidence: Look at the smaller size of their skulls, they said. However, women were able to prove them wrong as they increasingly gained access to schools and progressed in learning. Meanwhile, the public continued to raise concerns that education will hamper or delay a girl’s pursuit of a husband.

Opposition to women’s education was common even among the most educated in society. Educators, with support from the public, turned to another argument: Women, whose bodies are already known for their frailty, are possibly putting their reproductive capacity at risk by pursuing intellectual activities. Unfortunately, scientists as well propagated this absurdity. They claimed too much brain work could harm a woman’s fertility, and that her reproductive system can’t biologically develop while engaged in intensive studies. That argument was documented in a well-known book by Harvard-educated Dr. Edward Clarke titled Sex in Education (1873). He warned that a girl must not “work her brain over mathematics, botany, chemistry, German, and the like”8Edward H. Clarke, Sex in Education; A Fair Chance for Girls (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1884), 126, https://archive.org/26/items/sexineducationor00clariala/sexineducationor00clariala.pdf. because it could “divert blood from the reproductive apparatus to the head”9Ibid. impairing her ability to bear children.

Despite the opposition, girls were able to attend schools but mainly for elementary education. The curriculum was focused on religious topics and domestic skills since all girls were groomed to be ideal mothers and wives. Beyond basic literacy, they also learnt to sing and play the piano. Over the decades, the battle for elementary and also higher education for women was victorious but it remained available to only a small number of them who were born in wealthy families, able to afford the expenses.

At the heart of the above arguments was opposition to any distraction from the maternal role women played. The opponents would’ve been flabbergasted to see mothers today juggle work, children’s activities, housework, physical exercise, appointments, homework help, grocery shopping, reading, time with friends, and more while still finding time to sleep at night.

11. The challenges hurled at mothers who dared to work

At the turn of the twentieth century, those mothers who joined the labor force had to face the problem of where to leave their children while they’re at work. Day nurseries (childcare centers) would become a reliable service only in the past few decades. So you might’ve had to leave your children, who could be toddlers alone all day (remember, at minimum 12-hour shifts), but that meant they’re exposed to harmful, or fatal, dangers from broken glass to fire. Burns, falls and bath drownings were common. You could leave them with older children, who might still be school age children (5 to 8 years old) to look after them but that never reduced the risks. You could also take them to the factory or industrial site where you work. Some of those children were injured or lost their lives in tragic accidents by working mothers letting them play around limb-breaking machines.

The overall mortality rate of children of working mothers was higher than the average. Thankfully, many neighbors and relatives were often understanding to the hardships that mothers face and helped looking after their children in their absence.

It appears superhuman, and rightly so, for a mother to work for 12 hours at a physically demanding job, then go home to look after, let’s say, four children. It should also be noted that these workers were cramped in claustrophobic, filthy factories — a far cry from our office-based, air-conditioned work with legally-mandated rest breaks. Worst of all, their society, especially its elite, saw them as “bad mothers” who weren’t able to exclusively care for their children.

12. Getting married or pregnant is a sure way to lose your job!

Men believed that women had a role to play, a natural one, negating any necessity for them to compete in the public sphere. Many complained about being in the presence of obviously pregnant women showing the “animalistic side” of their sexuality. Men’s eyes were too delicate for such displays! These petty and parochial views from the Victorian period, survived into the mid-twentieth century.

Low pay and limited work options were not the only challenges for women looking for work. From the outset of the Industrial Revolution and into the 1960s—that’s more than a century—women who were able to get the lowly paid jobs were fired as soon as they got married. Many did not wait around to get fired, they just voluntarily left upon learning they’re pregnant. The discriminatory policies applied to you if you were, for example, a flight attendant at TWA or TEAL (the forerunner of Air New Zealand). A book titled Social History of the United States explains:

The belief that working women should or would resign when they married was so entrenched in the culture of 1920s that some cities and states fired teachers who married. In some cities, these rules also applied to secretaries, librarians, and social workers. In addition, some banks and insurance companies would not hire married women.10Brian Greenberg and Linda S. Watts, Social History of the United States – The 1900s (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2009), 42.

The main reason women faced discrimination at work was essentially their capacity for pregnancy. Employers knew that pregnancy follows marriage, and maternity leave was something they were not willing to accommodate nor bear its cost. Business owners didn’t find any reasoning behind their businesses paying benefits for a woman taking part in her “natural duty” of bearing children.

Even if you’re unmarried and working, you still have no prospects of job advancement because eventually you’re leaving to get married. A higher position at work would be wasted on you! You end up stuck at the lower end of pay, and at the bottom of the job hierarchy. However most businesses took the easy route and they just never hired women.

The suffering and impoverishment of millions of mothers in need of fair work opportunities did not dissuade decision makers. Business owners, philosophers, clergy, and even doctors agreed, albeit for various reasons, that a “two-career” marriage is objectionable. Doctors, for example, promoted the view that women are too frail to work long hours, and it could be detrimental to their procreative abilities. (Not a completely outlandish view given that women, on average, had shorter lifespans, more health risks, and most workplaces were sickeningly filthy.) The decades-long controversy was laid to rest when maternity leave laws were established, and working women of the 1970s were able to keep their jobs while they’re pregnant.

13. Sorry, your sexual conduct disqualifies you from government aid!

Reformers in the 19th century fought for poor and destitute mothers to receive financial government aid. Between 1910 and 1920, Western countries started enacting “Mothers’ Pensions” programs. There was a catch: only “good mothers” were eligible. Employees assessing your eligibility were intrusive and would have wanted to ensure that you had a “high moral standing.” They’d visit you in your home and through your answers try to find clues on your sexual history. You were not eligible if you were divorced, deserted, or known to have violated “proper” sexual conduct. In some cases, women failed to quality because they were not regular churchgoers or were already working for wages.

Besides sexual history, race was also a factor in determining who’s a “bad mother.” Immigrants and ethnic minorities, like African American mothers, were automatically disqualified. The winds of change eventually blew through these assistance programs and they became less authoritarian and a truly viable economic option for families.

14. Contraception: Wouldn’t they abandon motherhood for unrestrained sex?

Birth control was always a challenge that women had to grapple with. Traditionally, there was only a handful of options available. Abstaining from vaginal penetration was perhaps the most effective for obvious reasons. Another option was coitus interruptus (the penis is withdrawn prior to ejaculation), which was highly ineffective because, as science later proved, pre-ejaculation fluid also contains sperm. Those two options then, as now, were unpleasant and unrealistic. Also some women couldn’t fully rely on men’s sense of self-control to withdraw at the right moment.

Lactation (breast-feeding) was another popular and natural form of birth control (technically known as the lactational amenorrhea method or LAM). It was the age-old method of spacing out children. It stops your body from ovulating (and subsequently menstruating), a process without which a pregnancy can’t occur. That’s the reason, in ancient Egypt for example, mothers breast-fed for the first 3 years. The main challenge though is that you have to be exclusively breastfeeding your infant, and even then, it becomes unreliable after the first six months postpartum.

Birth control is one area that has consistently been mired in myths and misinformation: Ancient Egyptian women inserted into their vaginas crocodile dung as a contraceptive (that probably did the trick thanks to the foul smell) and Victorian women thought it’s less likely a pregnancy would occur without a female orgasm.

Between the 17th and 19th centuries in the West, women’s reaction to men’s breast fetishism was to squeeze their torsos in cleavage-enhancing corsets. These breasts were protected from the “vulgar activity” of breastfeeding. Sexual use only! Ironically, the mothers who delegated this degrading burden to wet nurses found themselves soon enough pregnant again.

Contraception might bring to our minds images of “childFREE” women pursuing solo travel experiences around the world, exciting professional careers and copious amounts of uncommitted sex. What contraception meant to a woman from the 19th century was entirely different. Non-marital sex and voluntary childlessness were radical and unthinkable ideas to most women at the time. Their only desire was to limit their family size. Jodi Vandenberg-Daves talked of their desperation in her book Modern Motherhood: An American History:

[T]he overwhelming majority wanted simply to stop having more babies than they could afford or than their health could sustain. “I have never rebelled at motherhood and no one on earth is more devoted to their home and children than I am,” wrote one woman who sought contraception. “I feel like I’ve had enough children.”

You might think, if not for the sake of maternal health and lower infant mortality, at least the obvious connection between family size and poverty would motivate practically everyone to welcome new contraceptive solutions but that never happened. During the period, from the mid-1800s, when the earliest artificial contraceptives were available, until the pill was put on sale in the 1960s, contraception was controversial and illegal in most Western countries. For example, it was legalized in Canada only in 1969.

Wouldn’t these devices allow “sexual passion” to burn in married women that they might even “demand” sex from their husbands? Would wives enjoy sex too much that they eschew their maternal duty? Would unmarried women be able to have sex without fears of public shaming as a result of illegitimate pregnancies? Would the “right kind” of mothers (read: white, upper and middle class) have even less children than they already do, while the “unfit” mothers (white and working class, or black or immigrant women) swamp the nation with their babies? These anxieties were not unfounded or unreasonable for their time, though any non-sexist, non-racist person today should respond with “yes, and they should have the right to do so.”

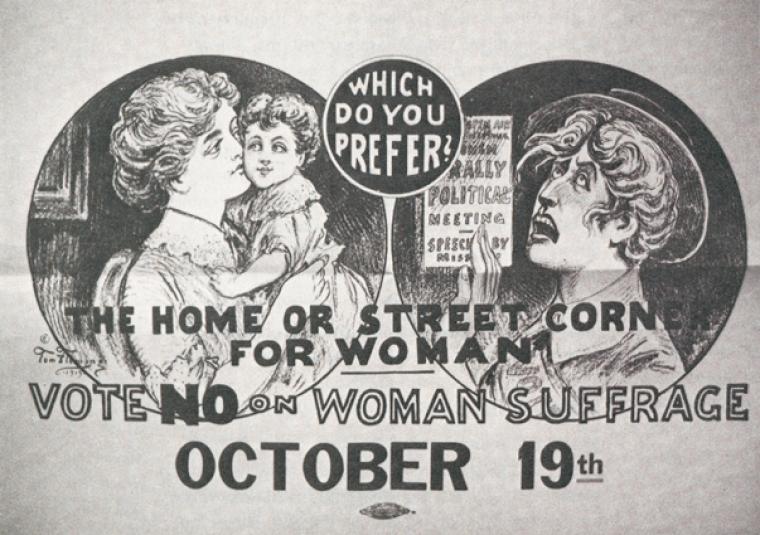

In the 19th century, even feminists opposed contraception. The only method they accepted was the natural (refuse sex or time it around your period), which, of course, had never been reliable. They and other advocates of women’s rights focused on battles like the right to vote, the right to own property and the right to refuse sex from husbands. The latter was their flimsy response to the issue of unplanned pregnancies. Birth control had no place on their agenda.

Another reason feminists rejected contraception was due to their conventional association with prostitutes. Furthermore, they worried that the use of these devices might backfire by setting the bar even lower for men, married and unmarried, already exploiting women for prostitution.

The all-male religious, political and medical establishment was also in opposition. Religious leaders’ main concern was the preservation of women’s chastity and their traditional maternal role. They feared the separation between the sexual and maternal functions. Till today, the Catholic Church considers artificial contraception sinful. Physicians born to such culture were no different and viewed women’s duty of reproduction at risk of birth control innovations.

Ordinary men were, not unlike the rest of society, opposed to birth control, but perhaps their opposition was not as fierce as the “establishment.” It might be true that men feel a surge of macho pride when they see themselves surrounded by many children of their own, but during the economic changes of the 1800s, it was understood that the more children they have, the more poverty they’ll suffer as a family, and being the breadwinner, men realized they’d be under even more pressure to bring more food to the table.

Opposition to contraception was finally codified in law in 1873, as part of a major anti-vice campaign by Postmaster General and evangelical Christian, Anthony Comstock. The “Comstock laws” enforced a ban that lasted six decades on mailing or distributing any information or instruments of sexual nature. The original target might have been men mailing pornography (books and prints), but the real victims were women seeking information on birth control. He saw both groups as equally immoral. Any distribution of contraception-related information or devices was a crime punishable by fines and imprisonment (and some women did go to jail).

As such, not only was the early technology of contraception often failing women, but also the laws took their reproductive rights away. Health officials and advocates of birth control had to discontinue their pioneer work and abide by the “gag rule.”

Even during the 1930s Great Depression, when most families were severely impoverished and unemployment was at 25%, the pleas of women who could barely afford feeding themselves were not heard and family planning continued to be a taboo topic.

But the prohibition was never complete. If you lived during the 19th century, with some difficulty you could’ve had access to contraceptive devices. The douching syringe was one of them. It was made a of metal or glass tube which you inserted into your vagina to wash out the semen after intercourse. They had to advertise it as a feminine hygiene device because selling it as a “contraceptive” would be illegal. In reality, it was only a scam. Despite that it remained popular from the mid-1800s until the contraceptive pill replaced it in the 1960s. Being an unregulated market allowed for misleading claims which were never authenticated.

Vaginal sponges, vaginal suppositories, and cervical caps (“womb veils”), among other devices, were obtainable, all of which were often dosed in a spermicidal agent before use. Rubbers, (you know, condoms) were also available. No longer condoms had to be made out of animal intestines (sheep guts), as in the pre-industrial times. For the sake affordability, they were reusable! The reliability of all of the above methods and the individual products varied. There was a lack of information, misinformation and misuse which made their efficiency more like a gamble.

From the 1920s, just like women’s contraceptive devices had been sold as “female hygiene” products, manufacturers were able to publicize condoms as a “security” or “protection” from venereal diseases. These infections were little understood but known to transfer during sex.

Empty euphemisms and false advertising were two ways around the Comstock campaign. Some women from these generations, despite the risk, continued to surreptitiously gain access to whatever birth control methods were available. Only in 1936, doctors were allowed to distribute contraceptive information, and finally the Comstock laws were invalidated in 1965.

Men always considered women responsible for the use of contraception. And when an intercourse resulted in a pregnancy, out of wedlock, they often walked away. In such cases, lack of clear biological connection worked in their favor. That apathetic attitude of men towards sex became more of a problem when non-marital relationships were common in the 1960s, while there was still no sex education or access to contraception for unmarried women. Women risked all: unwanted pregnancies, ruined sexual reputation and shame in their communities.

It was not merely a cultural attitude that put the brunt of contraception on women, all the emerging technologies of the past 200 years did the same too. Perhaps the background of how men have long handled, or mishandled, “the morning after” is why the question keeps coming up in the media of whether men could ever be trusted with a male contraceptive pill, should it become a reality.

15. “Race Suicide”: Could women be trusted with reproductive freedom?

The contraception debate took place while the West was witnessing an unprecedented drop in fertility rate. In the United States, among the whites, it was at 7.04 children per woman in 1800, 5.42 in 1850 and 3.56 in 1900. It kept dropping (to 2.22 in 1940) then “baby-boomed” between 1950 and 1960 to 3.53. It continued to fall and reached an all-time low of 1.84 by 2015.

What is the reason behind the birth rate decline and the desire for contraception? Upper and middle class women in the 19th century adopted a different approach to motherhood. Families started to devote more time and energy to nurturing each child individually. They paid large sums of money for each child’s education and training in non-academic activities. That kind of child-rearing is manageable with only three or four children. Also, unlike the struggling working class and women of color, they didn’t need too many children to be sent off to work in factories.

In the early decades of the 20th century, many saw the drop in birth rate and the demands of women for more control of their own reproductive choices as part of a Soviet conspiracy to undermine the West. US President Theodore Roosevelt (1933-1945), commenting on the declining birth rate, attacked mothers who refused to have as many children as their predecessors. He accused them of being criminal and collectively committing a “race suicide.” His admonishment was aimed at the “fit” mothers (white and middle-class). He, like most politicians of his era, thought that the fertility of minorities and immigrants was too high. The ambition of the time to take away reproductive control from mothers, could be summed up in one of his quotes: “I wish very much that the wrong people could be prevented entirely from breeding… Criminals should be sterilised and feeble-minded persons forbidden to leave offspring behind them.”

Though this article is mainly focused on the West, it’s worth noting that other countries didn’t just have anxieties over birth rate but implemented policies to applaud mothers who fulfilled “their duty” and contributed more children than others. In Communist countries, like USSR and Romania, you receive a medal from the head of the state if you had 10 children. You also received the title of “Mother Heroine.”

The Romanian experiment in particular that rewarded fertile mothers, penalized childlessness through taxes and criminalized abortions was so effective that it created catastrophic results. Between 1966 and 1989, more than 9000 women died from illegal abortions11Gheorghe Boldur-Lățescu, The Communist Genocide in Romania (New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2005), 121. and around 170,000 babies were dumped to the care of the state who are now adults living with a range of disorders and behind a disturbingly high crime rate.

Society rushes to put the responsibility of reproductive decisions on mothers alone but many external factors directly affect family size decisions, from government policies, to social and economic conditions, to the cost of raising children (the constant rise of which is largely to blame for the birth rate drop).

16. Compulsory sterilization for the lower classes and the “lesser races”

In a dark irony, policy makers offered birth control only to “bad mothers,” or forced it in may cases as explained below, while prohibiting its use for the rest of society. President Roosevelt was not alone in his support for sterilization. The science of Eugenics, “racial betterment” through selective breeding,” had many proponents among the Western elite in the first half of the 20th century.

One of those was Dr. Clarence Gamble, of Procter & Gamble, the world’s largest maker of personal care products. He, and other proponents, found eugenic sterilization and contraception, to be the solution to the perpetual problem of poverty. At least that was the public purpose of their mission. It would’ve been harder to ask for cooperation from leaders of the targeted minority groups if their message was overtly racist. The truth is that the racist proponents of eugenics assumed women of racial minorities, like African Americans, were not intelligent enough to use contraception properly, hence they couldn’t be trusted to make their own decisions.

Contempt for the lower classes and the “lesser races” was at the heart of the program. In the United States, “between 1907 and 1964 more than 63,000 people were sterlized,”12Wilma P. Mankiller, Gwendolyn Mink, Marysa Navarro, Gloria Steinem, Barbara Smith, The Reader’s Companion to U.S. Women’s History (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998), 573. most of whom were women. The program targetted the poor but particularly focused on women of childbearing age in Black communities and Indian reservations. In most of the cases, sterilization was forced or offered after a questionable consent. A lesser known fact about Hitler’s Germany is they they modeled their compulsory sterilization program on the American one, though they expanded it on a monumental scale.

17. Abortion and the horror of back-alley clinics

For many women, abortion was the only family planning option available even though it was illegal almost everywhere. The morality crusade of Comstock made it illegal for American woman until 1973. Before then, you would’ve had to ask around for a sympathetic doctor to help you. Many were just seedy characters in the proverbial back alley whose abortions were occasionally botched and fatal. But since it’s criminal to begin with, no one was prosecuted. Women were so desperate that they were willing to risk their own lives to keep the size of their families down and some died trying. Some even opted for self-induced abortions often with disastrous outcomes.

Most of those who sought abortion were married women in the 19th century, though that was reversed by the mid 20th century. The demand for abortion was so high in the post-war era that it created an underground market of unlicensed abortion providers. Jodi Vandenberg-Daves describes it in her book, Modern Motherhood:

Women’s memories included an abortion provider smoking during the procedure, another smelling badly of alcohol, and an abortion performed without any anesthesia. One woman whose pregnancy was the result of a rape said she was offered a $20 refund on her $1,000 abortion in exchange for a sexual favor, and her experience was not unique. Follow-up care was usually the woman’s responsibility. One woman remembered going to an abortionist who “said not to call if I had problems.”

18. The brutal punishment for out-of-wedlock pregnancies

When ancient Greek and Roman women couldn’t abort their own pregnancies, they carried their children to term then killed them after delivery. Infanticide was a fact of life for thousands of years. Unwanted pregnancies did not always carry the same sense of shame. The Mosaic law, however, stipulated that an unwed mother should be punished by death. Christianity could be seen as more lenient in comparison: An unwed mother carried a lifelong stigma, which was passed on to the “bastard” child. But the shame was so great that there was little sympathy for rape victims.

Fathers, even if they acknowledged their deed, were under no legal obligation to help the mothers and their children. That’s not surprising because society always put the brunt of responsibility on women. So, an unmarried mother is someone who failed to control her own “passion” or curb her man’s desires. In the best of times after death ceased to be their punishment, they became social outcasts, disowned by family, shunned by acquaintances, condemned by the Church, and many had to resort to begging on the streets or turned to prostitution to feed themselves and their children.

In the medieval era, the Breast Ripper13Julie Ann Tharp and Susan MacCallum-Whitcomb, This Giving Birth: Pregnancy and Childbirth in American Women’s Writing (Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 2000), 23. (known also as the Iron Spider), a metal instrument to mutilate the breasts of women, was used to punish them for pregnancies out of wedlock (i.e. fornication) and self-induced abortions, among other crimes. As for their children, they would be cared for by the Church, typically in monasteries. During the 1600s and 1700s, unwed mothers were prosecuted for fornication and commonly sentenced to whippings14Merril D. Smith, Sex and Sexuality in Early America (New York: New York University Press, 1998), 90.. Very few men (only the ones who admitted paternity) were convicted. Around the same time, orphanages and foundling hospitals were built around Europe. Mothers left their infants at their doors, sometimes with tokens that are kept safe by nurses to help identify them years later.

During the Victorian era, maternity homes were established to shelter the “fallen women” and their infants. Unwed mothers were considered a threat to the cohesion and conformity of society who were best hidden away. Maternity homes served as rehabilitation centers. That practice continued into the following century, but from the postwar 1940s until early 1970s the rationale behind it was different. It was no longer a transgression that required atonement but a psychiatric problem.

In 1965, two Harvard University psychiatrists wrote, “Every unmarried mother is to some degree a psychiatric problem…the victim of mild, moderate or severe emotional or mental disturbance.”15Rickie Solinger, Wake Up Little Susie: Single Pregnancy and Race Before Roe V. Wade (New York: Routledge, 2000), 87. And instead of encouraging young mothers to look after their children, itself part of the punishment, parents and social workers coerced them into letting go of their infants and giving them up for adoption. It’s best to have your child grow up with married parents, they were told. How could the kid have a normal childhood without a father present? Social policies that considered them neurotic or unstable disqualified them from the very role of motherhood. After all, if they can’t behave responsibly with their sexual urges, they couldn’t be responsible for newborn children either.

Maternity homes of early twentieth-century were funded by the state, and managed by religious organizations like the Salvation Army, Catholic Church and Anglican Church. Young mothers were meant to eventually leave to go back to normal life, get married and have children. Canada, for example, had 60-80 maternity homes, most of which closed during the 1980s.

In many ways, the infamous Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home of Ireland was a representative of such homes. It operated between 1925 and 1961 and nuns were trained as nurses and midwives. The mothers, under their care, were treated like servants and their unpaid work was partially to reimburse the Home for its services. The film, Philomena (2013), which is based on yet another Irish maternity home, shows how little compassion nuns, whose lives were devoted to chastity, had for the young mothers who had failed to curb their lusts. Infants suffered an alarmingly high death rate and died from infections and malnutrition. There was a media outrage in 2012 when it was revealed that hundreds of them were buried in a mass unmarked grave as if they’re subhuman, and that up to 1,000 children might have been trafficked to the US for illegal adoptions without consent from their mothers.

Despite the common perception of the 1950s as a period of conservatism, premarital sex was on the rise, and so were out-of-wedlock births. The decade started with unprecedented 4% of births outside marriage and reached 5.2% by 1959. Family status in the community was at risk if their daughter is known to have had out-of-wedlock sex, and even worse, if it resulted in a pregnancy. Here’s what families did to protect their daughters’ sexual reputation according to Jodi Vandenberg-Daves:

An important way to avoid social shame and expulsion from school for white girls and women was to discreetly disappear to a maternity home, where they endured quiet isolation and a hurried birthing experience, often followed by separation from their babies. Some never actually saw their babies, and many were coerced into signing adoption papers. These girls returned to school with a story about a sick aunt who had needed them for a few months and without a baby.

The policy of baby relinquishment for adoption was standard in many countries from Canada, to the United Kingdom and Australia. Many mothers, from that so-called Baby Scoop Era, recall never seeing their children — by the time they were back to consciousness, their newborns were gone. Native Canadian infants were fostered into white families. Aboriginal children faced the same fate in Australia. They’re dubbed the “Stolen Generation.” The racial element to the suffering inflicted on those single mothers is part of the racism experienced by minorities in recent history. Native American mothers were also singled out as incapable of taking on the tough task of modernization themselves, hence hundreds of their children were taken away.

Some mothers in the past three decades were able to reunite with their biological children. Ann Fessler documented their stories in her book, The Girls Who Went Away: The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Children for Adoption in the Decades Before Roe v. Wade. That policy came to an end in the U.S. in the 1970s following the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision which legalized abortions. Other reasons at play were the widespread use of the contraceptive pill and a simultaneous cultural shift away from adoption. Even though adoption ceased to be an embarrassing family secret and families had more freedom to adopt across racial groups, the demand for it has been dropping sharply since then.

There are no national records for out-of-wedlock births in pre-industrial times, but it was likely between 116Gregory Clark, “Chapter 4: Fertility in the Malthusian Era” (research paper, University of California, Davis, 2003), 5. This document can be found at: http://faculty.econ.ucdavis.edu/faculty/gclark/papers/book2003-4.doc and 3 percent. In most Western Countries, the percentage has been rising sharply along with an increasingly tolerant attitude. In the U.S., in 1950 it rose to 4%, 10.7% in 1970 and 40.7% by 2012 (PDF). France, Sweden and Norway have exceeded 50%.

19. Breastfeeding: A history of judgmental attitudes and conflicting messages

Wet nursing was a job opportunity for anyone with breasts who needed an income. Many of them were unmarried, immigrants or ones whose infants didn’t survive the first few weeks post-delivery. Some were so poor that they abandoned their own infants to orphanages to nurse exclusively other babies for pay. The customers could be a family who had lost the mother during childbirth, or a mother who did not have adequate milk supply, or one who just had enough money to able to avoid the “disgraceful” practice of breastfeeding, as explained earlier.

The mother typically treated the wet nurse who had moved into her home, at best, with uneasiness. She’s there to do her maternal job, after all. The wet nurse was often reminded that she’s inferior—a “human cow” whose milk is her only asset. Then there was also the concern that the father might take a liking to the new female tenant or just take advantage of her. In these cases, more mistreatment from mothers was guaranteed.

The ancient practice of wet nursing was not always safe. Infant mortality, for example, was “horrific” in French foundling homes and hospitals during the 1700s and 1800s, due to the transmission of syphilis to newborns. Many of the working-class wet nurses had a history of offering sexual services through which they would contract syphilis. In other cases, healthy wet nurses acquired the disease from syphilitic infants. That two-way transmission of disease helped create a desire for an alternative. From around the beginning of the 20th century, sterilized bottled milk was available and for mothers who could afford it, there was also pasteurized milk formula. (The pasteurization process removes germs.) As wet nursing slowly faded into history, bottle-feeding became the norm.

Infant formula became the norm in most Western countries. “Whereas 80 percent of American infants had been breast-fed before 1920, by 1948 only 38 percent of babies were breast-fed at one week of age.”17Andrew Smith, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, Volume 2 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 103. It dropped to 18 percent by 1956. For the next two decades, into the 1970s, breastfeeding rate stayed at an all-time low where less than a quarter of infants were breast-fed in their first week. Mothers were indoctrinated through physician advice and advertising that their milk is barely adequate while formula is superior. Mass advertising completed the metamorphosis of breastfeeding mothers into anxious consumers. Thus, one of the most personal and natural acts between a mother and child was beset by unceasing meddling. Those who were reluctant to abide were denounced for not following scientific advice and depriving their children from a growth-boosting product, that is infant formula.

At the end of 1970s, the message was reversed and mothers were encouraged to go back to breastfeeding. The results have been promising since then. In 2011, 79% of newborn infants were breastfed. However, the historical insecurity mothers felt regarding the quantity of their own milk since the commercial success of formula never receded. Today, mothers are silently judged negatively when they’re seen in public bottle-feeding their infants.

Breastfeeding in the “public sphere” comes with its own challenges. It should be expected given that Western women spend most of their daily lives away from the privacy of homes unlike before. However, many people, perhaps still influenced by outdated views, feel uncomfortable around breastfeeding, even though the majority of mothers cover up. There seems to be no shortage of stories on that subject in the media of late. Fortunately, breastfeeding in public is not only treated as legal, but also a basic right of women.

20. Why did one of half of the human race oppress the other?

Two simplistic words could encapsulate the suffering of mothers: biology and culture. Technological and medical advances have been emancipating women from the former. Culture, though, withstood ideological battles for generations until feminists and advocates of equality were able to reshape it. It’s understandable that women be at the mercy of their own biological limitations in pre-scientific times, but cultural subjugation is actually perplexing.

Subjugation of any people in history could be explained through theories of economic benefits, military expansion, racial superiority or religious discrimination. But there’s no such definitive answer to explain the universal subjugation of men to their own wives, mothers and daughters, millennium after millennium. If you spin the globe and arbitrarily point your finger at any territory or country, it’ll likely be a place with a record of at least some of the following forms of female oppression: social customs, religious beliefs, legal restrictions, domestic violence and sexual objectification. (Only a few ancient and indigenous tribes could be excepted.) But why?

Did men dominate women because they’re bigger and stronger? Or was there an unspoken motive to keep women perpetually as servants and housekeepers? Is it true, as some radical feminists claimed, that jealousy is the main reason which is induced by men’s inability to bear children? Or a deep desire to control women’s reproductive decisions? Perhaps an evolutionary biologist could argue that the root cause is a testosterone-fueled competition between men to get a shot at immortality through offspring. Or an anxiety caused by the lack of paternal confidence and the primordial suspicion expressed as “mother’s baby, father’s maybe.”

Do men suffer from an “underlying psychological disorder,” and their “oppression of women is [just] a symptom,” as psychology lecturer, Steve Taylor argued? Should we surrender to the indictment of radical feminist, Marilyn French, who said “all men are rapists” and they just can’t help it? Or do men deserve sympathy for their “hardwired” lack of control in face of female sexual allure? Could it be that the very act of sex naturally empowers men, the aggressors, over women, the recipients? Or is it that men are just acting out of revulsion at the female body and its “peculiar” secretions from menstruation, sex, childbirth and lactation?

As a 21st-century husband and father, I find it challenging to zero in on the real causes. Looking at it from the other side, I find women’s mistreatment at the hands of their fathers, husbands and sons, the very ones on whom they depended, similarly hard to comprehend. Sentiments which most likely will arise in female readers are frustration and puzzlement: Why generations of women acquiesced to injustice with barely any resistance?

21. The importance of acknowledging women’s social progress

We have come a long way since the perfect woman was one who gets married—fertile and subservient. We have come a long way from the time a shameless physician lectured in 1870: “as if the Almighty, in creating the female sex, had taken the uterus and built up a woman around it.”18Helen King, Midwifery, Obstetrics and the Rise of Gynaecology (Aldershot, Hants, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2007), 181. Feminism–being the equality of the sexes in its purest sense–has triumphed and its ranks were not filled with only women: There were men from various backgrounds which included physicians, social workers, attorneys and even some clergy. The gradual expansion of women’s rights is one of the greatest achievements of Western Civilization. As English historian, Paul Johnson, wrote:

Indeed it is the protean ability of Western civilization to be self-critical and self-correcting…that constitutes its most decisive superiority over any of its rivals.

Mothers now lead healthier and happier lives. They can pursue higher education, refuse sex from their husbands, keep their jobs when they get pregnant, demand and get a divorce if they want, and have safe access to contraception and abortion. Men also benefited from feminism: Women share with them the burden of household expenses and paternity leave has been legislated to allow fathers to spend more time with their children. Oh, and sex is better too. A healthy couple who understand and take precautions, and none of whom feels inferior find more pleasure in sex.

Alas, this positive picture is barely acknowledged by the currently dominant form of feminism. Yes, there’s still much to aim for, from flexible work hours to fair representation in senior political and business leadership, but the disdain of mainstream feminism towards Western culture and achievements in science and technology is disheartening at best.

The anti-science movement embraces some risky practices which have endangered the lives of women and children since the beginning of time: home birth, water birth, anti-vaccination for children, eating one’s own placenta and lotus birth, where the umbilical cord is left attached to your baby after birth until it falls off naturally several days later.

It’s important to remember that any civil rights revolution is prone to extremism, and women could be sexist too! One has to wonder at this point whether feminism lost its original vision when its devotees are waging campaigns directed at the whole population of men for “manspreading” on public transport (men raping public space, as they do) or “mansplaining,” by which they shut down the very dialog that helps create a civilized society. Have you heard about the “manflu”? It’s no exaggeration to believe that such tactics threaten the future of the whole movement. Judging by these women on the extreme left, you can’t miss the pendulum’s full swing from misogyny to misandry.

There is probably a worthy cause for women’s equality in Silicon Valley, but perspective matters: Tens of millions of women, from Nigeria and Saudi Arabia, to Thailand and India still suffer from most of the miserable conditions mentioned above. For so long, Western feminists righteously just looked the other way while their sisters in the developing world are being victimized by rape, child marriage, acid attacks, honor killings, female genital mutilation, sex trafficking, domestic violence, access to education and representation in politics. How many among today’s Western feminists dare to challenge Islamic or Hindu traditions about women?

Acknowledging social progress is less about celebration and more about faith in Western ideals such as humans rights and gender equality. Mothers and non-mothers will continue to benefit from the awareness of their rights and opportunities. Western ideals, no matter how despised they might be by some in the West, are destined to liberate those suffering in other parts of the world. Let’s not forget that if it weren’t for Western influence, Chinese foot-binding and the Indian Sati (“widow-burning”) would have survived to the present time.

If you’re a mother in a Western country at this junction in history, you’re fortunate because you’re a member of a generation more empowered than any that has preceded it. And if you’re a mother in a developing country where women are still second class citizens, despite the limited support from the West, your empowerment is closer than ever, thanks to technology and medicine.

Endnotes