The blue-highlighted quotes below are the eleven declarations of the Futurist Manifesto. The rest of the quotes presented here are from other Futurist articles and manifestos. Here is the entire text of the manifesto in English or original French.

What is the Futurist Manifesto and how it became such a big deal?

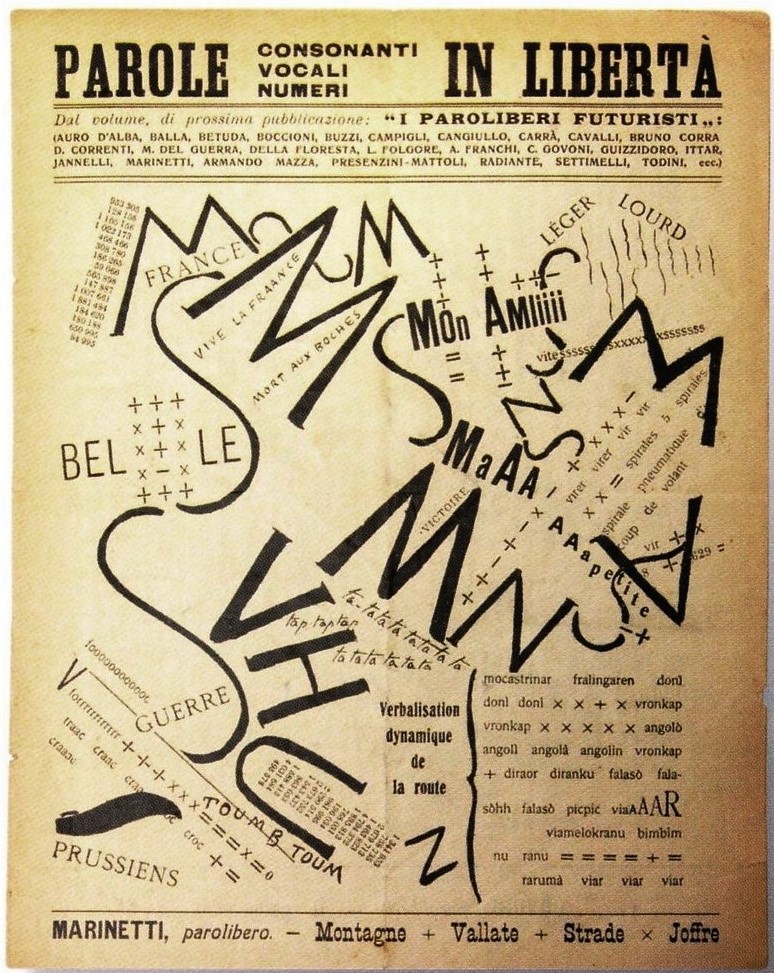

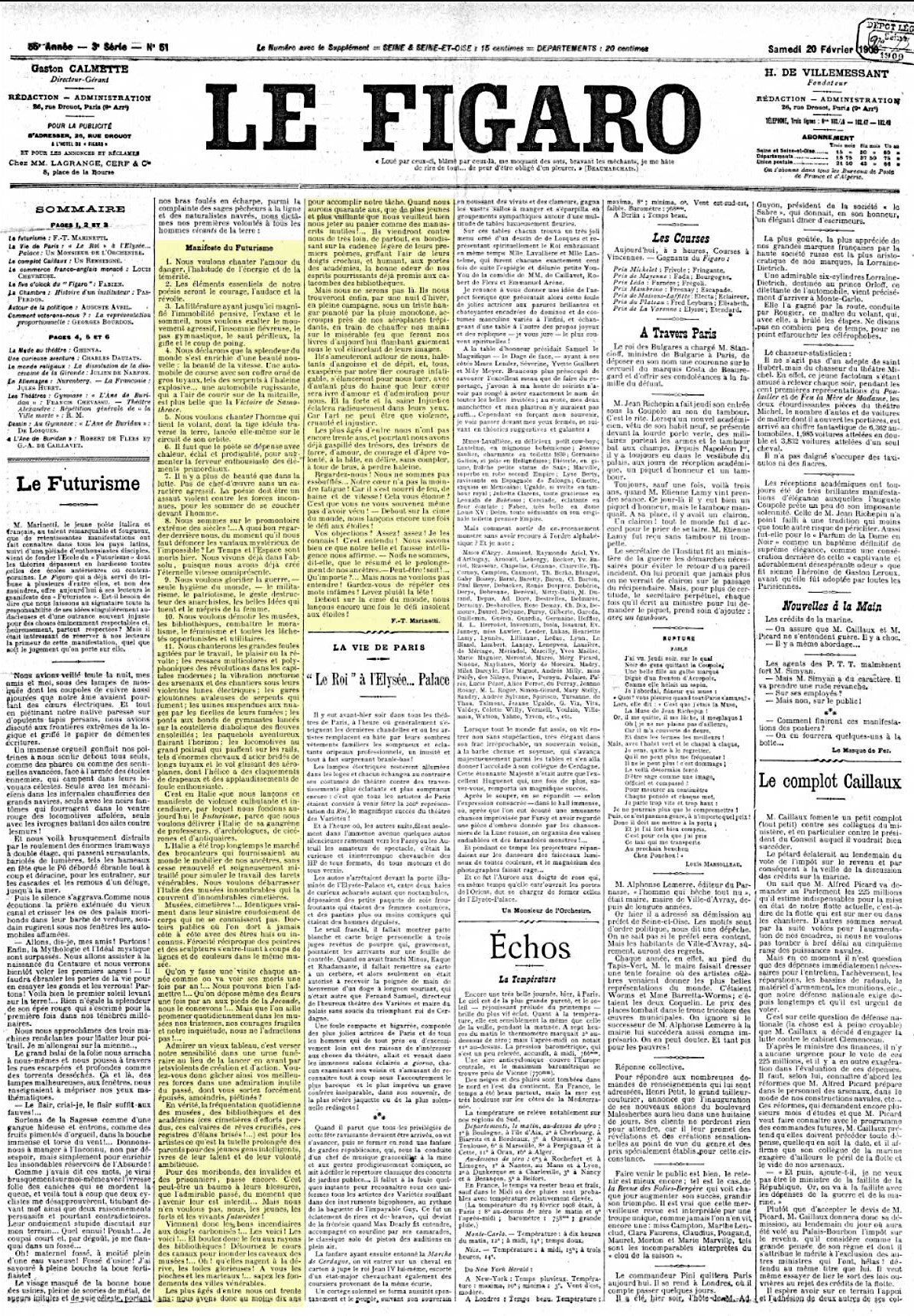

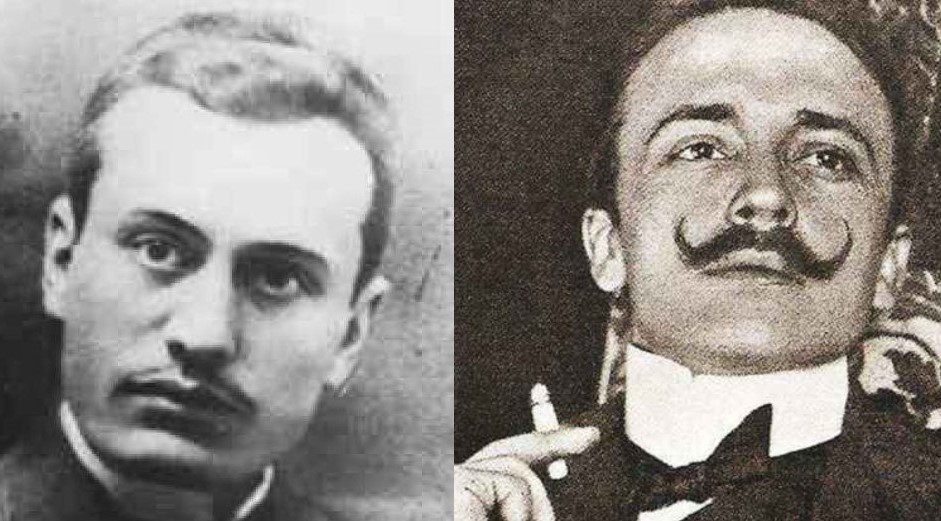

In the first decade of the 20th-century, a group of Italian writers and artists agreed that their declining country is in dire need of “rebirth,” i.e. a cultural regeneration. They were young and rebellious. For a country “stuck in the past,” industrialization, technology and war could bring about the required changes, according to them. The leader of the group was a second-rate poet but a master of early propaganda. He gave his movement the grandiose name of Futurism, as in “the future has arrived.” Then he secured an amazing publicity stunt by publishing their Futurist manifesto on the front page of the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro. The ambitious Futurists aimed to reshape society. For years later, they would publish manifestos covering wide topics such as painting, sculpture, architecture, theater, poetry, linguistics, fashion, dance, music, cinema and cuisine. However, the most important writings were about politics and war, which were, in retrospect, proto-fascist and highly influential in the early days of the Italian Fascist party.

The three main problems facing Italy according to the Futurists and their corresponding solutions/themes in their Manifesto:

First Problem: Around 1900, Italy, that was once an empire, is a nation in decline

A constant aspect of culture in any society is a friction between its traditional and progressive elements; those who resist change and their opponents who think forward. Futurists, a group of artistic Italians, saw what every Italian could see, that something is wrong about their home country: Culturally and industrially backwards. Politically and economically irrelevant. A hotbed of crime, corruption, poverty and disease. While the central government is weak, the Catholic Church is keeping the main culture mired in traditions. Italians were fleeing in droves to other countries. Italians had nothing to brag about except their ancient Roman heritage and the fact that centuries ago, ironically, the Renaissance started there. Meanwhile, these young Italians could not help being gripped with envy as they watched how other western European countries are developing.

Futurist response: Destroy museums! Reject the past!

Futurists took it upon themselves to start with changing the culture. They believed that, as artists, they should not be isolated in studios creating “symbolic” art on canvases that end up on walls in museums, but should be actively engaged in solving society’s problems. In short, artists should activists. For years, Marinetti spoke of his despise of romantic poets, those who write about “the moonlight” and sensuality. Marinetti, being a poet, singled them out in his manifesto as only of value to society when they challenge their fellow citizens and join the cultural battle:

The poet will have to do all in his power, passionately, flamboyantly, and with generosity of spirit, to increase the delirious fervor of the primordial elements.

There is no longer any beauty except the struggle. Any work of art that lacks a sense of aggression can never be a masterpiece. Poetry must be thought of as a violent assault upon the forces of the unknown with the intention of making them prostrate themselves at the feet of mankind . [Articles 6 and 7 on the Manifesto] 1F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 14.

Futurist artists dedicated poems, artworks, articles and theatrical gatherings to singing praises of values needed for “modernization”:

Courage, boldness, and rebellion will be essential elements in our poetry. [Article 2 on the Manifesto] 2Ibid., 13.

They understood that they will be resisted by those who want to cling to the past, but they were ready to use all methods including violence to bring about their modern vision:

We wish to destroy museums, libraries, academies of any sort, and fight against moralism, feminism, and every kind of materialistic, self-serving cowardice. [Article 10 on the Manifesto] 3Ibid., 14.

Read here about those who embraced state-sponsored iconoclasm last century as a fast track to modernization.

The opening line of the manifesto demonstrates that they are willing to resort to extreme measures to bring about their vision:

We want to sing about the love of danger, about the use of energy and recklessness as common, daily practice. [Article 1 on the Manifesto] 4Ibid., 13.

The celebration of youth was a major element in their movement:

[A]s far as the great Futurist hope is concerned, all authority, all rights, and all powers will be violently torn from the hands of the dead and the dying and given to young people between twenty and forty years of age. 5Ibid., 84.

The Futurist idealism and defiance was present in many of the bombastic statements by their leader Marinetti:

Just look at us! We’re not exhausted yet! Our hearts feel no weariness, for they feed on fire, on hatred and on speed!…Does that surprise you?… That’s logical enough, I suppose, as you don’t even remember having lived! Standing tall on the roof of the world, yet again we fling our challenge at the stars! 6Ibid., 16.

In the same year Marinetti published the Manifesto, he imagined the battle against traditional forces and wrote prose full of brutal imagery:

“Gutless scum! Gutless!… What are you howling about, like cats being skinned?… Are you scared we’re going to set a light to your miserable little hovels?… Well, we aren’t just yet!… After all, we’ll have to keep ourselves warm somehow next winter!… For the moment, we’re happy enough just blowing up all the old traditions, like broken-down bridges!… War, you say?… Well, yes, exactly; that’s our one hope, our raison d’être, our sole desire!… Yes, war!… Against your lost, because you’re not dying off quickly enough; and war too, against all the other deadbeats that get in our way!

Yes, our very sinews insist on war and scorn for women, for we fear their supplicating arms being wrapped around our legs, the morning of our setting forth!… What claim do women have on us, or for that matter, any of the stay-at-homes, the cripples, the sick, and all the caution-mongers? Rather than have their timid little lives torn apart by their dismal little anxieties, by their restless nights and fearful nightmares, we prefer a violent death; and we glorify it as the only one fitting for man, beast of prey that he is.

We want our children to follow their whims untrammeled, brutally opposing the old and jeering at everything that has been consecrated by time! 7Ibid., 23.

Second problem: Italy is lagging behind in industrialization and technological innovation

In the two decades (1890s and 1900s) preceding the founding of Futurism, most citizens of west Europe and the United States were enjoying modern comforts. It was during that the 1890s that consumerism, thanks to new inventions, emerged where shoppers could buy products like ready-to-wear clothing or bottled Coca-Cola. Shoppers could browse through products in catalogs from home or visit the multi-storey retail buildings, where they could even have the amazing experience of being in an escalator (the first of its kind was installed in 1898 in Harrods of London). The following decade, the 1900s, witnessed the beginning of the Eastman Kodak company (1900), the first zeppelin flight (1900), the electric typewriter (1901), the first radio transmission across the Atlantic Ocean (1901), indoor air conditioning (1902), the first successful flight of a self-propelled aircraft by the Wright Brothers (1903), the first movie theater in Pittsburgh (1905), sound radio broadcasting (1906) and the first commercial color photography (1907). During the same decade, some inventions from the previous decade were becoming popular among consumers like the home phonograph (gramophone).

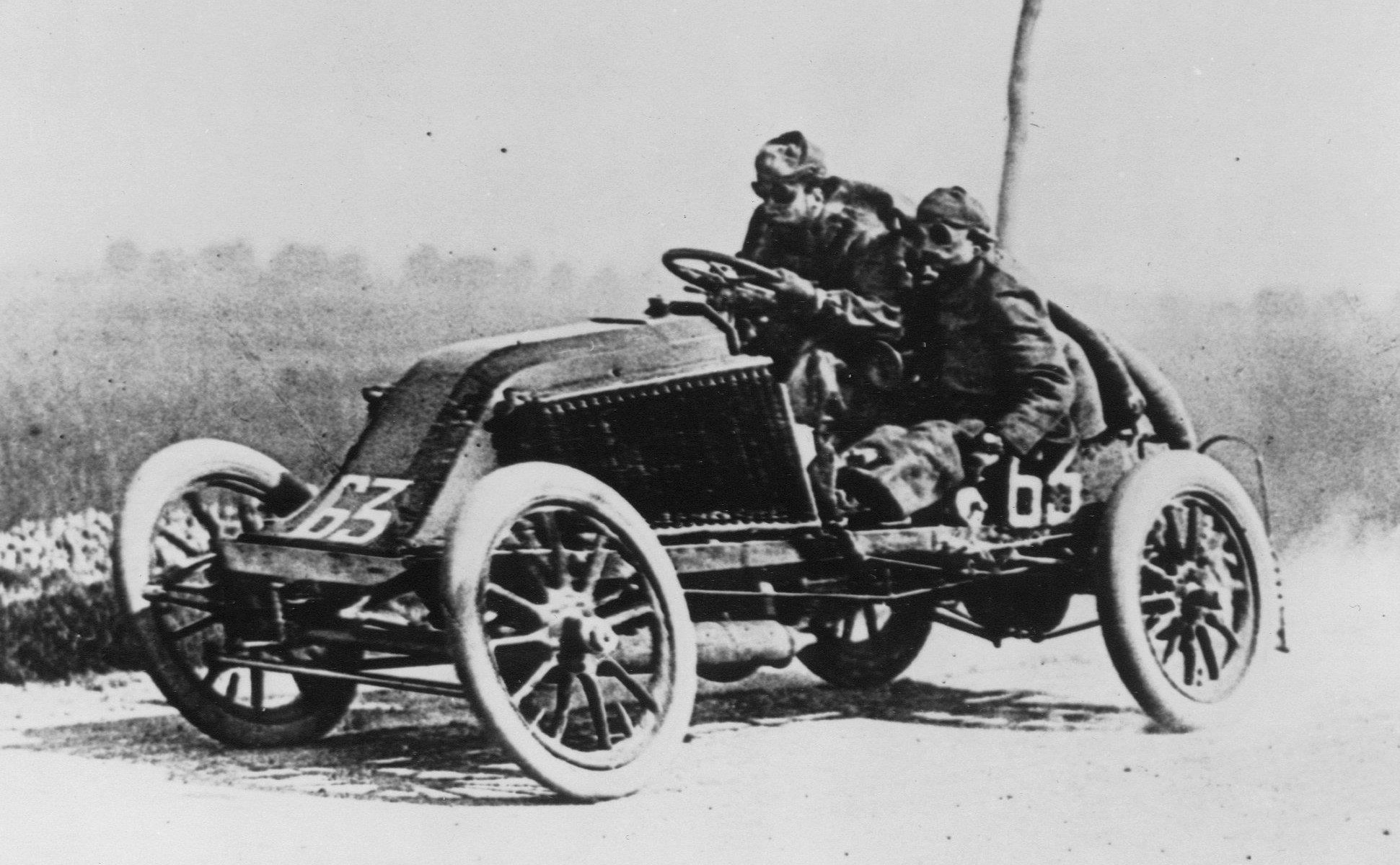

Commercial production of automobiles began in 1891. The first race of gas-powered cars took place in Illinois in 1895. During the 1900s, cars were becoming more popular and affordable. In 1908, Ford Model T was introduced as the first truly accessible car for the masses. The Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1914) introduced improvements in steel production which led to great advancements in shipbuilding and transportation. Progress in manufacturing materialized in railroad networks, sewage systems and water supplies far beyond major cities. Though the above inventions might seem quaint to us, they arrived at a pace that was dizzying to society. Marinetti captured that sentiment in 1913 in the following quote:

An ordinary man can be transported by a day’s train journey from a godforsaken little town, on whose deserted squares the sun, the dust, and the wind silently amuse themselves, to a great capital city, bristling with lights, action and noise… The inhabitant of a mountain village can each day follow with trembling anxiety the newspaper reports on the Chinese in revolt, the London and New York suffragettes, Dr. Carrel’s experiments, and the heroic sleighs of the polar explorers. The faint-hearted, stay-at-home citizen of any provincial town can indulge himself with the headiness of danger at the cinema, watching a big-game hunt in the Congo. He can admire Japanese athletes, Negro boxers, indefatigable American eccentrics, the most fashionable Parisian women, just by spending a dime at the music-hall. And when finally he is lying down in his bourgeois bed, he can enjoy himself to the costly, far-off voice of a Caruso or a Burzio. 8Ibid., 121.

None of the above inventions appeared in Italy. In fact, when the Italian inventor and pioneer, Guglielmo Marconi, demonstrated the use of radio waves as a communication system, he received no support in Italy, from government or business. He had to move to London where there was commercial and scientific interest.

Futurist response: Let’s celebrate industrialization and the “machine age,” symbolized by the automobile!

The Futurists wondered why Italians can’t enjoy and contribute to photography, sound recording, electric light, cinematography, radio, telephones, telegraph, trains, cars and airplanes? So they chose the glorification of technology to be central to their message. Products of industrialization like automobiles, steamships and locomotives were heavily present in their paintings and poetry. They saw in industrialization beauty unmatched in art or nature:

We shall sing of the great multitudes who are roused up by work, by pleasure, or by rebellion; of the many-hued, many-voiced tides of revolution in our modern capitals; of the pulsating, nightly ardor of arsenals and shipyards, ablaze with their violent electric moons; of railway stations, voraciously devouring smoke-belching serpents; of workshops hanging from the clouds by their twisted threads of smoke; of bridges which, like giant gymnasts, bestride the rivers, flashing in the sunlight like gleaming knives; of intrepid steamships that sniff out the horizon; of broad-breasted locomotives, champing on their wheels like enormous steel horses, bridles with pipes; and of the lissome flight of the airplane, whose propeller flutters like a flag in the wind, seeming to applaud, like a crowd excited. [Article 11 on the Manifesto] 9Ibid., 14.

Italian Futurists: The first to love and worship the machine

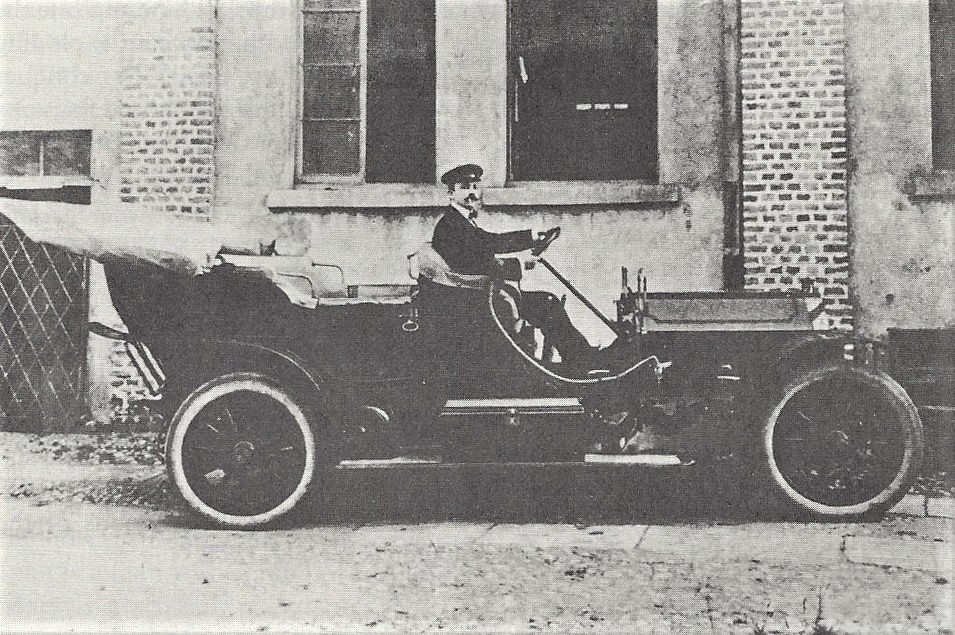

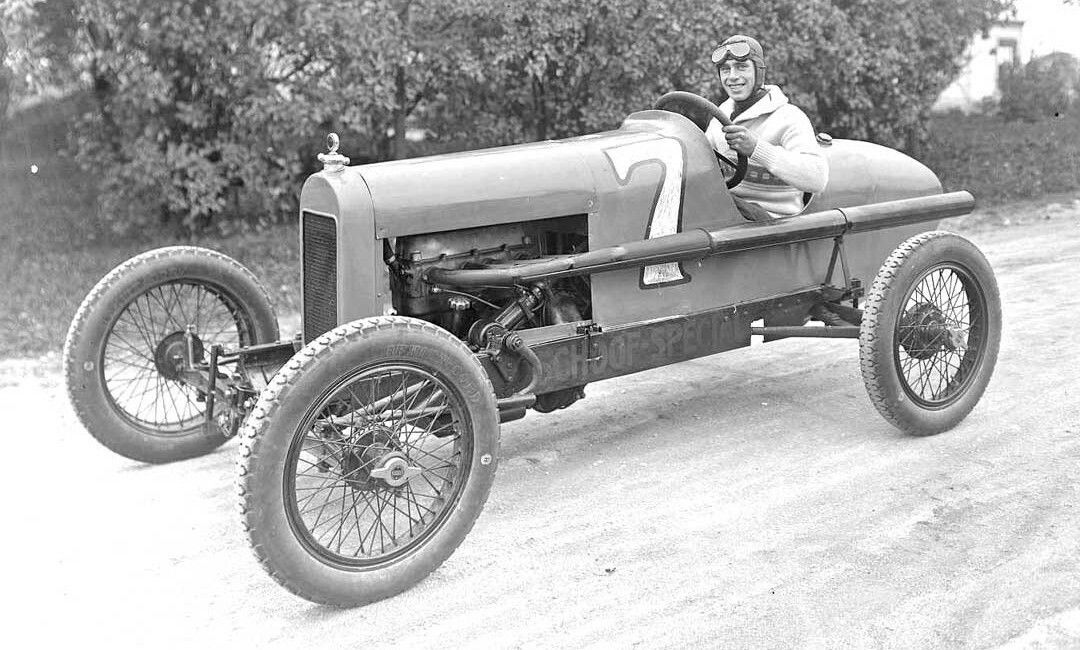

In October of 1908, F. T. Marinetti almost killed himself in an accident driving his beloved Fiat Cabriolet. Although his car was destroyed, he survived and used that episode in the founding mythology around the origin of the Futurist movement. To the Futurists, automobiles in particular were highly symbolic of the new era. Not only because they owe their existence to great innovations of industrialization like factory production lines, electric power generation and the use of the recently-invented internal combustion engine, but also for what they stood for. They represented an unprecedented modern phenomenon among young men fascinated by such instruments of speed and danger. That was immortalized in one of the most famous lines of the manifesto:

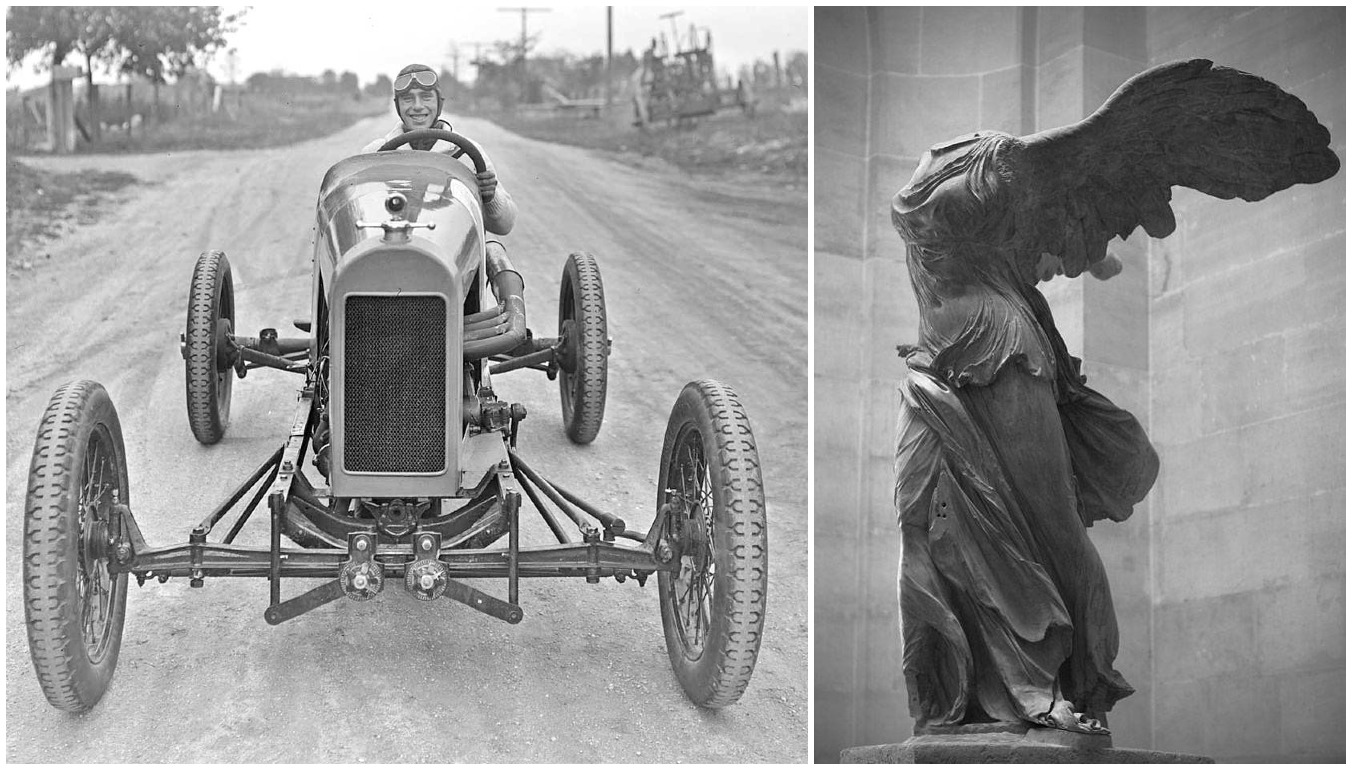

We believe that this wonderful world has been further enriched by a new beauty, the beauty of speed. A racing car, its bonnet decked out with exhaust pipes like serpents with galvanic breath…a roaring motorcar, which seems to race on like machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Winged Victory of Samothrace. [Article 4 on the Manifesto] 10Ibid., 13.

Marinetti above is comparing a speeding automobile to an iconic Greek sculpture which was in the Louvre then and still is. In an era before airplanes captured the popular imagination, the racing car was appropriate for comparison. Marinetti did not just pick any classic sculpture to belittle, but one of Nike, the revered Greek goddess, in motion, well, flight! Perhaps that sculpture represented several traits he detested: ancient, feminine, gentle, clearly fragile and merely symbolic. On the other hand, Marinetti found speeding cars masculine, modern, metallic, powerful, aggressive and amusingly dangerous. Such were the traits he welcomed as noble values of modern life.

The founder of Futurism wrote an article titled “The New Ethical Religion of Speed.” Obsessed with motion, Marinetti considered “Dinamismo” as a name for his new artistic school. In admiration of the recent technology of electricity, “Elettricismo” was also on the shortlist, before they settled on Futurism. Their technophilia eventually would turn towards airplanes, in the final decade of the movement. At that time, aerovita (airborne life) could have been the new name of their movement. Their adoration of airplanes, and Marinetti’s masterful understanding of what appeals to the public, resulted in aeropittura, (aero-painting) aeropoesia, (aero-poetry) aerocultura (aero-sculpture) and aeromusica.

Read here why the Italian poet Marinetti spoke of speed in religious terms

Their adoration, as artists, of the modern city and machine guns, and everything in between, ran in the opposite direction of the previous generation of artists, the “weak” French souls who expressed their “fin de siècle” anxiety and alienation in response to modernism. The Futurists did not just believe that technology would improve life, but it would improve our capacity as humans. Marinetti believed that the improvements in communication and transportation, and other areas will eventually breed a new man-machine hybrid, who’s capable of transcending human limitations. A new era has dawned:

We stand upon the furthest promontory of the ages!… Why should we be looking back over our shoulders, if what we desire is to smash down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We are already living in the realms of the Absolute, for we have already created infinite, omnipresent speed. [Article 8 on the Manifesto] 11Ibid., 14.

He described the “new man” as one who

“fuses with iron, who feeds upon electricity and understands nothing beyond the desire for danger and day-to-day heroism.” 12Ibid., 44.

They called on their supporters to…

Have faith in progress, which is always right, even when it is wrong, for it is movement, life, struggle, and hope. 13Ibid., 251.

No longer culture should glorify priests or professors:

Against tears of beauty, shed over the tomb, we set the finely chiseled features of the pilot, the chauffeur, and the aviator. 14Ibid., 44.

The manifesto had expressed the same idea:

We wish to sing the praises of the man behind the steering wheel, whose sleek shaft traverses the Earth, which itself is hurtling at breakneck speed along the racetrack of its orbit. [Article 5 on the Manifesto] 15Ibid., 13.

In 1915, he reaffirmed that he had no regrets writing, years earlier, his controversial line saying a racing car is more beautiful that the Winged Victory of Samothrace, then he defiantly delivered one of his most horrific statements on the topic:

I’ll offer you now an explosive gift that expresses our thoughts even better: “Nothing is more beautiful than the framework of a house being newly built.” To a well-built house we prefer the iron skeleton of a house being erected with its girders the color of danger—landing strips for aircraft— with its myriad arms clawing at the sky and combing out the stars and comets, with its aerial platforms, from which the eye can survey the wide expanse of the horizon. We adore that framework, with its rhythm of pulleys and hammers and beating hearts. And occasionally—so be it—the piercing cry and heavy thud of a workman falling, a great splash of blood on the pavement! 16Ibid., 250.

Third problem: Italy is militarily weak and losing out on territorial expansion (New Imperialism)

That era was a period of intense competition between nations that went beyond industrialization and technological innovation. Indeed, there was an international competition in manufacturing automobiles and early experiments in aviation, but they were also rivals in colonization. The Futurists, like most westerners then, admired territorial expansion by European nations which were becoming, or had become, established empires. The rivals were Britain, France, Germany, Spain, Belgium, Portugal, Denmark, Austro-Hungary and even the relatively young nation, USA. They all took part in the so-called New Imperialism, colonizing territories in Africa and Asia. Italy had an adventure during the European “Scramble for Africa” which brought them a humiliating defeat in what is labelled the Italo-Ethiopian War (1895 – 1896). In the racist terms of its period, it was even more humiliating that Africans (Ethiopians) defeated Europeans. Only a year after publishing the manifesto, Marinetti would cheer on Italy to colonize and brutalize Libya.

Futurist response: Integrate into culture the adoration of violence and war

The Futurists hoped to see the pro-war attitude spread among the public and becomes enmeshed in the national culture. (The Futurists were among the first to line up for enlisting when Italy joined World War I.) They considered war rejuvenating and unifying for the nation. War, as they saw it, is capable of freeing them from their stagnant state. In the orgasmic violence and bombardments of war, they saw creative destruction.

We wish to glorify war—the sole cleanser of the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive act of the libertarian, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women. [Article 9 on the Manifesto] 17Ibid., 14.

The last three words exposes the misogyny of the Futurists: Heroes are men, not women. Soldiers and combatants are men, not women. So “scorn for women” is what keeps men dedicated to their heroic deadly mission! The misogyny of the Futurists, advertised with these words, followed them for many years.

The most important elements of fascism could be traced to Italian Futurist writings years earlier.

Long before Hitler Youth, they proposed paramilitary training for children and for blending war propaganda with art:

Up to now, literature has extolled a contemplative stillness, rapture, and reverie. We intend to glorify aggressive action, a restive wakefulness, life at the double, the slap and the punching fist. [Article 3 on the Manifesto] 18Ibid., 13.

The Italian Futurist poet, F. T. Marinetti, was a misogynist and a proto-feminist all at once.

The Futurists considered militaristic rivalry and conflicts between nations necessary. Even healthy.

Is not the life of the nation rather like that of the individual, who fights against infection and high blood pressure by means of the shower and the bloodletting? Peoples too, in our view, have to follow a constant, healthy regime of heroism, and indulge themselves with glorious bloodbaths! 19Ibid., 61.

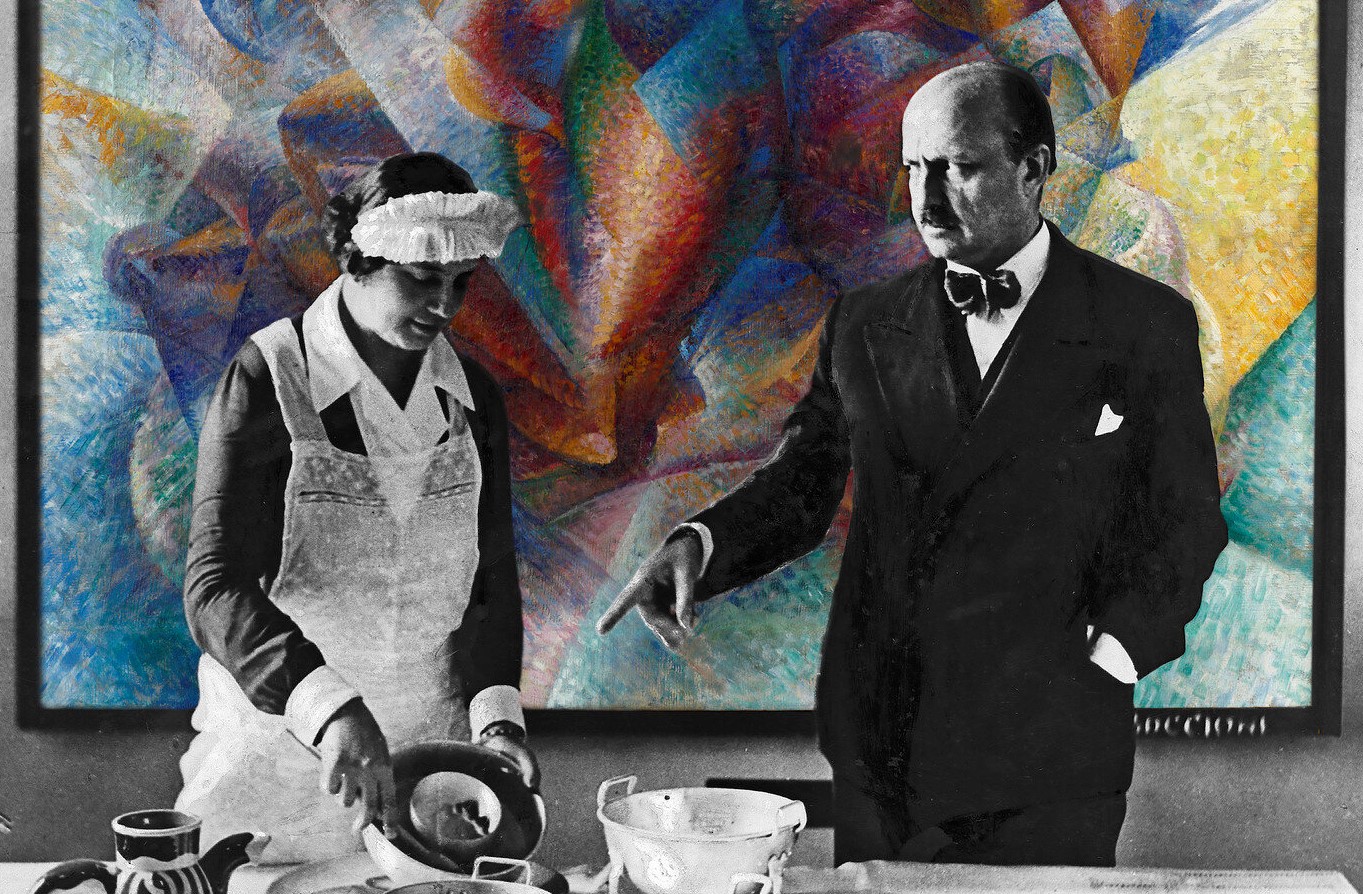

In what amounts to gastronomical blasphemy in Italy, Marinetti condemned pasta as “no food for fighters.” He wrote a 1930 manifesto on Futurist cooking urging Italians to abolish it from their cuisine since it “mentally paralyses” them, inducing “lassitude, pessimism, nostalgic inactivity and neutralism”.

Fascism, that was yet to emerge, reared its head early among the Futurists who desired to marginalize, if not antagonize, anyone who would not be a young fighting man—a soldier-citizen. That is how a culture commences to be militarized:

A continuous progress, with the wresting of power from the dead, the old, the slow, the indecisive, the vile, the velvet-tongued, the delicate, the effeminate, and the nostalgic. Day-to-day heroism. Let’s experience all dangers and all struggles. Let’s dirty our hands digging trenches, yet be ready for the pen, the oar, the rudder, the swipe, the fist, and the rifle. 20Ibid., 233.

How the Futurist train finally arrived at fascism?

Here are the above points summarized to demonstrate how Futurist ideas became the foundation of fascism:

a. Modernization and industrialization are needed in Italy.

b. Traditional culture and historical baggage must be discarded.

c. Resistance should be met with revolutionary violence.

d. Youth and masculinity are celebrated because the mission needs young, aggressive men.

e. A ruthless and autocratic government should lead the nation and enforce modernization “from above.”

f. The government should be militaristic, capable of waging industrial war.

g. It should also be imperialistic, seeking to expand its territories overseas.

As the Futurists believed, change, i.e. modernization, could only be imposed “from above,” and that is where their politicized art movement comes in to lead the nation. In an open letter, written by Marinetti in 1913, he summarized all the main ideas of his manifesto in a typical fiery statement:

Futurism… is a new way of seeing the world; a new reason for loving life; the enthusiastic glorification of scientific discoveries and of modern machines; the flag of youth, of strength, and of originality at all costs; it is a huge gob of spittle aimed at all the depressing traditionalists; a steel collar against the habit of backward-looking stiffnecks; an inexhaustible machine gun pointing at the army of the dead, of the gouty and the opportunists, whom we want to strip of their authority and subject to the bold and creative young; it is a stick of dynamite for all venerable ruins. 21Ibid., 105.

In the Futurist vision, people’s democratic participation in their modernizing program is not needed. The Futurists could not trust the masses with such a mission. Democracy and parliamentarianism would be eliminated as weak systems. National symbols and chants would replace the religious kind. A powerful army should rise up and be idolized by the masses. A Futurist (or fascist, as history would have it) government would use violence against internal opponents attempting to thwart its mission. And against external enemies threatening its existence. Individual rights pale in importance to the duty and demands of the state:

Today more than ever, the word “Italy” must take precedence over the word “Freedom.” All freedoms are ours, with the exception of the right to be cowards, pacifists, and neutralists. Every kind of progress must be sought within the confines of the nation. 22Ibid., 237.

All of the above became the key ingredients of the fascist rule that was only a few years away. Looking back, we know how the story ends. The story that started with the glorification of war, political violence, virility and ultra-nationalism ends with military parades and mass rallies. It ends with mobs calling for the extermination of those who do not belong. It ends with women marginalized and other minorities demonized. Mayhem and a society in tatters is how the story really ends.

How to judge Marinetti and his fellow Futurists?

We should come to terms with what Futurism actually stood for, and object to the tricks that some contemporary writers attempt to play. Intellectual tricks include claims that Marinetti may have supported war but not in the sense of a bloody conflict, just a cultural war. He harbored contempt for women, but not literally, only as a symbol of a “romantic tradition.” He called for the destruction of museums, but only metaphorically. He might have supported fascism but only temporarily until they showed their real colors! Well, was Marinetti’s Futurism proto-fascist and misogynist? Yes, it was both!

Downplaying the ties between Futurism and fascism as a “brief association” does not allow for an honest study. Marinetti’s allegiance to Mussolini and his fascist party continued to the last day of his life. Some writers even try to dismiss the early alliance with the Fascists as a naive mistake by the young Futurist artists who did not have the benefit of hindsight. That ignores the fact that the Futurists, in many ways, had identical views as the Italian fascists or even inspired them as they came into political existence. With that in mind, the Futurist movement should be viewed in its historical context as a sincere attempt by a generation of Italians trying to improve the dire conditions of their country, from which hundreds of thousands of immigrants had been fleeing.

Is there anything to admire about Futurism in the 21st century?

It is better to view Futurist art the same way we do the music of Richard Wagner or the poetry of Ezra Pound. We appreciate their art without subscribing to their views on politics or race. In fact that is exactly what happened when a Futurist sculpture was featured on an Italian 20-cent Euro coin. After all, the Futurist aesthetic was ground-breaking in representing the industrial age and the dawn of a new era.

While Futurist misogyny, war glorification and fetishization of violence should be left in dust-covered history books, there still might be more than their creativity and art to admire. For example, their courage to challenge traditional culture and institutions, including the supremely powerful Church, when it was radical to do so. Also, their unshaken optimism, though it was extreme, in a better future for humanity, thanks to technological progress and industrialization. Also, Marinetti was intelligent enough to foresee a culture obsessed with youth, speed and technology, which is still alive in Hollywood movies and pop culture. One particular characteristic of the movement is perhaps the most relevant to us today: their honest embrace of modern life and new technologies in contrast to those who hypocritically condemn modernity while enjoying its very products.

You might also like:

Futurism: On turning speed into a pseudo-religious experience

‘Speed is Divine’: Why the Italian poet Marinetti spoke of speed in religious terms

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

The misogynist who supported feminist causes—mostly inadvertently

The Italian Futurist poet, F. T. Marinetti, was a misogynist and a proto-feminist all at once

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

‘Destroy museums!’–Why an Italian waged war against the past

Those who embraced state-sponsored iconoclasm as a fast track to modernization

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Was Futurism proto-fascism?

The most important elements of Fascism could be traced to Italian Futurist writings years earlier

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Three possible reasons why Italy lagged behind Europe for centuries

Why Italy’s modernization has been, and continues to be, problematic?

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Futurists vs Romantics: Extreme views on technology and nature

Gazing at the stars, from Goethe, Marinetti to Google Sky

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Endnotes