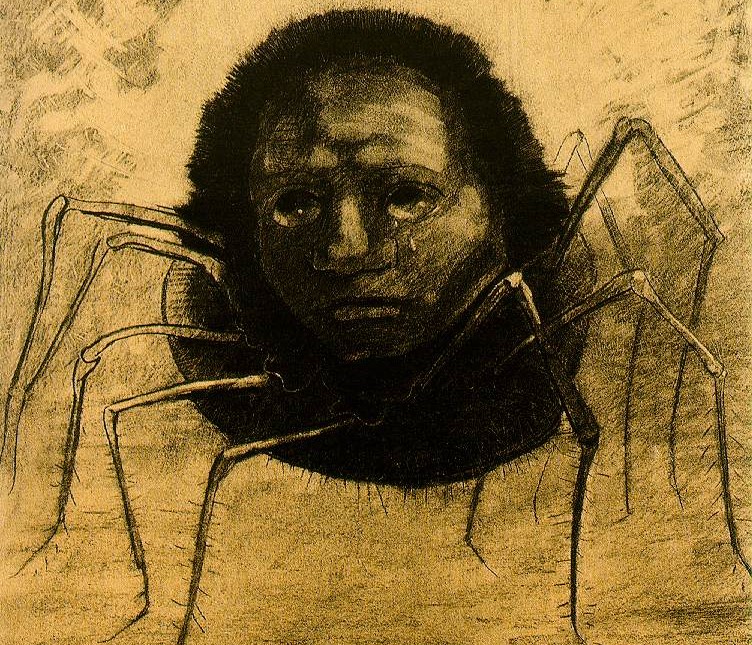

A major theme in The Metamorphosis revolves around how life is absurd and void of meaning. That’s what makes the book one of the greatest works of Absurdist fiction. It’s as if Kafka meant to answer the age old question of whether life is a comedy or a tragedy by writing a tragicomedy himself. The story opens with a bizarre and irrational event, which is also one of the most haunting opening statements in literature. A travelling salesman wakes up to realize that he had just been transformed:

When Gregor Samsa woke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed right there in his bed into some sort of monstrous insect.1Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis, trans. Susan Bernofsky (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2014), 21.

We’re told that he was a good son and brother who helped his family make ends meet. But we’re never told why he was transformed or whether he deserves it. It just happens.

Instead of being overwhelmed by this personal tragedy and how he’ll deal with it, the thoughts of his tiresome job keep crossing his mind. He reflects on the many times he wished he could quit that job if his parents and sister did not rely on that income. His main concern at this point is being late for work! For five years, being a perfect employee, he never called in sick or were late.

He doesn’t respond to his mother knocking on the bedroom door. Eventually, his manager comes to the apartment wondering why Gregor did not show up for work. He also knocks on Gregor’s door and warns him of the consequences, reminding him that his work has been less than satisfactory lately. Gregor promises from behind the door that he’ll be there right away. None of them, boss, parents or sister could understand his voice which had been transformed too. They all suspect that he must be seriously ill. With one of his many legs, Gregor opens the door and immediately apologizes for being late. They’re all horrified at seeing him, and still no one understands him. The manager runs out of the apartment. His father chases him back into the room with his cane and shuts the door.

Although, they were shocked at first, the family quickly accepts that their son is now a giant insect, and moves on to consider how they’ll adjust their lives to this new reality. There is never any talk of seeking help or attempts at understanding what befell Gregor in that bedroom. Even Gregor himself quickly adapts to his new body and starts climbing the walls and the ceiling for fun.

Due to the financial distress caused by Gregor’s inability to work, the family takes in boarders.

A moving moment amidst all the strange events, and perhaps the best respite from the theme of absurdity, was when Gregor heard his sister play the violin. He ventures slowly and unnoticed outside his room. He, and the readers, are reminded that on the inside, he’s still human, yearning to return to his natural and loving connections with those surrounding him.

Gregor’s sister began to play; on either side, his father and mother attentively followed each movement of her hands. Attracted by her playing, Gregor had ventured a bit further than usual and was already sticking his head into the living room.

[…][H]is sister’s playing was so lovely. Her face was tilted to one side; searchingly, sadly, her eyes followed the lines of notes. Gregor crept a bit farther forward and ducked his head down close to the floor so as perhaps to catch her eye. Was he a beast, that music so moved him? He felt as if he were being shown the way to that unknown nourishment he craved.

He was determined to creep all the way up to his sister, to pluck at her skirt and in this way indicate to her that she should come to his room with her violin, for no one here was rewarding her playing as he meant to reward her…[H]e’d had the firm intention of sending her to the Conservatory.2Ibid., 99-101.

That most beautiful moment is ruined as soon as one of the boarders spots the gigantic insect outside his room. In a way, the presence of Gregor himself is what brought an end to that touching moment.

His sister, who had been looking after him with love, feeding him scraps of food and cleaning after him, comes to the following conclusion:

“Dear parents,” his sister said, striking the table by way of preamble “things cannot go on like this. Even if you two perhaps do not realize it, I most certainly do. I am unwilling to utter my brother’s name before this creature, and therefore will say only: we have to try to get rid of it. We have done everything humanly possible to care for it and show it tolerance, I don’t think anyone would reproach us on this account.”

“She is right a thousand times over,” Gregor’s father murmured under his breath. His mother, still incapable of breathing freely, began to cough dully into her lifted hand, a lunatic expression in her eyes.3Ibid., 105.

Even his sister who was once his only friend is abandoning him. Gregor hears the family conversations and understands that he had become an unbearable burden to them. Then, at dawn, he dies.

“And now?” Gregor wondered, looking around in the dark. He soon made the discovery that he was no longer capable of moving at all. […] He remained in this state of empty, peaceful reflection until the clock tower struck the third hour of morning. He watched as everything began to lighten outside his window. Then his head sank all the way to the floor without volition and from his nostrils his last breath faintly streamed.4Ibid., 109.

Kafka wrote this as a “non-event” where it’s not clear whether his death is due to a suicide, broken heart, natural causes or a fatal injury (earlier in the story his father severely injured him by hurling an apple at his back).

The family now is in relief that Gregor is gone. His father:

“Well,” Herr Samsa said, “now we can thank God.” He crossed himself, and the three women [including the cleaning lady] followed his example. 5Ibid., 112.

In another scene of utter absurdity and disrespect, the cleaning lady gets rid of Gregor’s body and assures the family:

“[T]here’s no need for you to go worrying about how to get rid of that mess in there. It’s already been taken care of.”6Ibid., 116.

In the final scene, the family minus the main character look forward to a bright future. It’s as if their former breadwinner Gregor, the son and brother, who devoted his life to helping his family never even existed:

Then all three of them left the apartment together, something they had not done for months, and took the electric tram all the way to the open countryside at the edge of town. The car in which they sat all alone was entirely suffused with warm sunlight. Cozily leaning back in their seats, they discussed their future prospects, and on closer investigation it appeared that these prospects were not bad at all, for all three of their positions—something they had never before properly discussed—were in fact quite advantageous and above all offered promising opportunities for advancement.

The greatest immediate improvement in their situation, of course, would be easily achieved by moving to a new apartment; they now wished to take a smaller and cheaper but more convenient and above all more practical flat than their current one, which had been picked out for them by Gregor. As they were conversing in this way, Herr and Frau Samsa were struck almost as one while observing their daughter, who was growing ever more vivacious, by the thought that despite all the forments that had made her cheeks grow pale, she had recently blossomed into a beautiful, voluptuous girl. Growing quieter now and communicating with one another almost unconsciously by an exchange of glances, they thought about how it would soon be time to find her a good husband.

And when they arrived at their destination, it seemed to them almost a confirmation of their new dreams and good intentions when their daughter swiftly sprang to her feet and stretched her young body.7Ibid., 117-118.

You might also like:

The Little Red Schoolbook: The challenging bits on sex and drugs

Controversial advice on sex and drugs from the schoolchildren’s book

BOOK: THE LITTLE RED SCHOOLBOOK

A Wrinkle in Time: Is it blasphemous or too Christian?

Two reasons Madeleine L’Engle’s book was challenged by religious conservatives

BOOK: A WRINKLE IN TIME

Endnotes