In 1916, the Italian writer and founder of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944), wrote about a bizarre military practice in Japan with great admiration. But before we explore it, it’s best to understand the cultural and historical background.

The early days of Japanophilia

From around the mid-19th century, the Western public was fascinated by Japanese culture. Travelers to Japan wrote about it in romantic and stereotyped terms. The Japanese were sometimes depicted as either superhuman fighters or subhuman. One of the writers who popularized Japan in Western imagination was Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904), a Greek-born and Irish-raised author. He wrote several popular books on Japan around the end of the 1800s. Another one was Basil Hall Chamberlain (1850-1935). Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford (1837-1916) was the first writer to document, from a first-hand experience, the ritual suicide called seppuko, or hara-kiri. In books, fact was mixed with fiction, in stories about Japanese daily life, noble death and the Samurai. To a large extent, that has still not changed much in pop culture in the 21st century! Most probably Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was familiar with such writings on Japan.

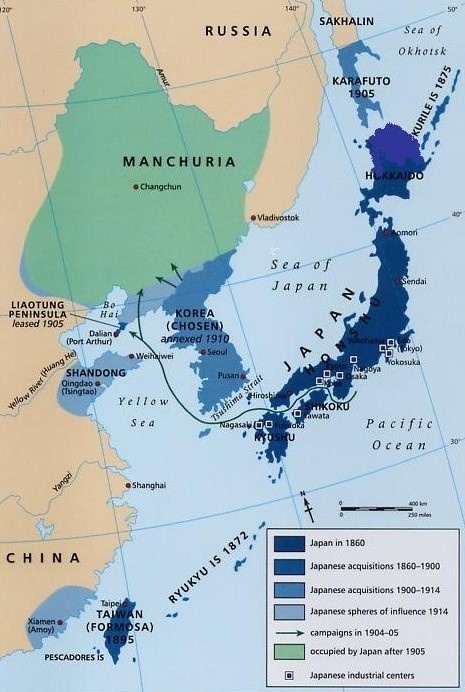

The Russo-Japanese War (1904)

In the first decade of the 20th century, a war broke out between the Empire of Japan and Tsarist Russia over the control of Manchuria and the Korean peninsula. Both empires had expansionist plans. Japan was ready to recognize the Russian takeover of Manchuria as long as they let them have Korea. Imperial Russia at that time was considered as a much powerful nation than Japan, although the latter had been industrializing rapidly for half a century. When Japan realized that their demands were ignored and that the Russian expansion will continue to reach even closer to them, they declared war on the Russians and eventually invaded Manchuria. Russia was humiliated and lost many more lives than their rivals over a period of a year and a half. One amazing fact, relevant to the below-mentioned urban myth, was about the naval battles: the Japanese torpedoes were so effective that thirty-two out of thirty-five Russian battleships were destroyed.

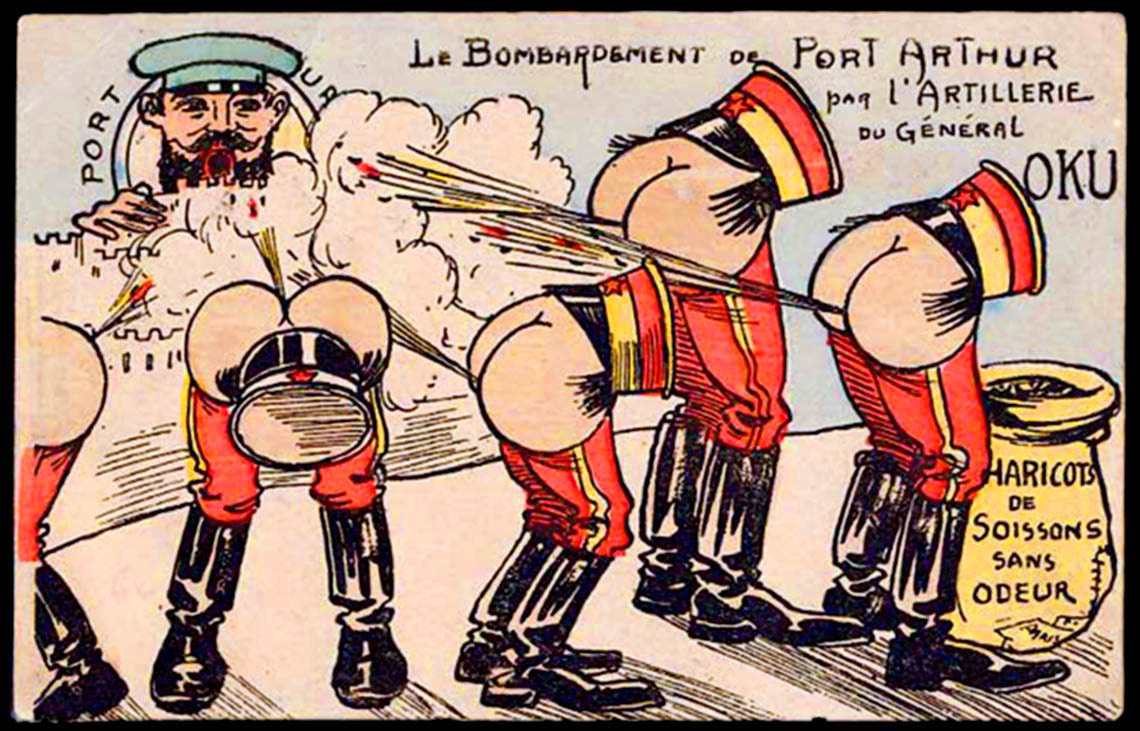

Western observers were so interested in that East-West conflict that they traveled to see it in real life. Propaganda and hateful material was rife on both sides. Eventually, the war concluded with a treaty through US President Theodore Roosevelt. From that moment on, the international balance of power, particularly in Asia, was different and the ramifications would be significant for the upcoming global war, that is WWI that was to start the following decade. Racial interpretations and fears appeared following the surprising Japanese victory. The victory puzzled people around the world since it was the first time that an Asian nation defeats a European power in modern times. To many in the West, it was unfathomable that “an inferior people of color” would militarily humiliate a European major army. There was also a religious dimension: How could an army of heathens vanquish a Christian one? Some cried “yellow peril” like Kaiser Wilhelm II, the German Emperor, who feared that Asians will rise up and subjugate Europeans.

Marinetti and the founding of Italian Futurism

The Russo-Japanese war took place during the years when Marinetti was formulating the fundamentals of his Futurist movement. He envisioned a modern world, starting with his home country Italy, that celebrates industrialization, masculinity and war. (Most of these ideas would survive into European fascism.) Years later, in 1916, he wrote about an urban myth in an article titled Birth of a Futurist Aesthetic, where the Japanese grind down the bones of their deceased fathers and heroes to create a new explosive mix for artillery shells. The result is a never-seen-before deadly power.

In Japan, they carry on a very strange trade in carbon derived from human bones. All gunpowder factories are working on the production of a new explosive which is deadlier than any other known hitherto. This terrible new compound has carbon from human bones as its principal ingredient, as this has the property of quickly absorbing both gases and liquids. For that precise reason, countless Japanese merchants go rooting about the battlefields of Manchuria, which are thickly strewn with corpses. All over those vast warring landscapes, in great excitement they dig out huge piles of skeletons. A hundred tsin (seven kilograms) of human bones fetch 92 kopeks.

[…]Skeletons of heroes will be ground down in mortars, without delay, by their children or their relatives or their fellow citizens, to be then brutally vomited out by cannon against enemy armies in distant lands…1F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 251.

In the same article, he calls on his followers to be like the Japanese:

Quickly! So as to clear the streets, let all the corpses of the beloved and the venerated be stuffed, without delay, down the cannons’ throats! Or, better still, let them await the enemy, gently rocking inside beautiful floating torpedoes, proffering their mouths full of deadly kisses. There will be an ever greater number of corpses. So much the better! The continuous increase of explosive substances will be of enormous value in our spineless world! 2Ibid., 252.

It is not clear where Marinetti would have encountered that myth, and there is no reason to assume that he made it up although he might have embellished its details. However, the reasons why it would appear in the first place are numerous. Perhaps the Russian enemy sought to associate the ingenuity of their destructive torpedoes to a barbaric tradition. Or perhaps racist observers wanted to brand them as “still primitives,” who make weapons from human bones, though obviously Japan matched, for the first time in history, the militarization and industrialization of European nations. Ironically, Marinetti, who was an early Fascist, never saw that urban myth through a racist lens. He probably saw it as a perfect embodiment of many of the ideals of his Futurist movement, which itself was proto-Fascist. Not only did he not find the Japanese inferior, as contemporaneous racists did, but he actually found them to be futurist, at least in regards to that particular “tradition”:

All glory to the unconquerable ashes of men, who come to life again in the Japanese artillery! My friends, let us applaud this noble example of an ingeniously fabricated violence. Let us applaud this noble example of an ingeniously fabricated violence. Let us applaud this fine slap in the face for all stupid cultivators of cemetery gardens. 3Ibid.

Futurist themes in the Japanese urban myth

The founder of Futurism was fascinated by that ghastly Japanese story because it contained several Futurist themes that make it a perfect representation of his ideas. Below are the main ideas from the myth next to Marinetti’s own quotes, the first of which is from his famous Futurist manifesto:

1. Glorification of war

We wish to glorify war—the sole cleanser of the world. 4Ibid., 14.

2. The fighters know that they will too one day will become gunpowder for other fighters. A symbol of heroism and violent self-sacrifice. But heroism and violence, in Futurism, are synonymous.

I believe that a people has to pursue a continuous hygiene of heroism and every century take a glorious shower of blood. 5Ibid., 19.

3. Soldiers crush the “skeletons of heroes” for the greater good. The world belongs to the young and the living.

[A]s far as the great Futurist hope is concerned, all authority, all rights, and all powers will be violently torn from the hands of the dead and the dying and given to young people between twenty and forty years of age. 6Ibid., 84.

4. The past is inferior to the future. No heroes or idols should stand in the way. No “cemetery gardens.” Children using their fathers’ bones for the battle.

Come on then! Set fire to the library shelves!… Divert the canals so they can flood the museums!… Oh, what a pleasure it is to see those revered old canvases, washed out and tattered, drifting away in the water!… Grab your picks and your axes and your hammers and then demolish, pitilessly demolish, all venerated cities! 7Ibid., 15.

5. Merchants of death have a role to play. Selling the bones of your ancestors and fellow citizens for the sake of the battle.

The proletariat of talented people will alone have the expertise to undertake the gradual, worldwide sale of our artistic [Italian] heritage, in accordance with the bill outlined by us nine years ago. […]

Our museums, when sold to the world, will become powerful reminders overseas of our Italian genius. 8Ibid., 349.

6. The battle never ends: The bones of the dead end up on the military machine’s production line to eventually reach the hands of the living in the form of weaponry.

War cannot die, for it was one of the laws of life. Life = aggression. Universal Peace = the decrepitude and death throes of races. War = bloody and necessary trial of a people’s strength. 9Ibid., 235.

7. Glorification of technology to the point that Marinetti envisioned a human-machine fusion, with superhuman and deadly powers. The image of human bones being fed into a machine could be a symbol of that hybrid:

We believe in the possibility of an incalculable number of human transformations, and we are not joking when we declare that in human flesh wings lie dormant. 10Ibid., 86.

A generation was born in Europe indoctrinated into such ideas that war, in and of itself, is heroic and glorious. It would take two world wars before Europeans look back at words such as those in the Futurist manifesto and realize that war is not “the cleanser of their world” but its “destroyer.”

Endnotes