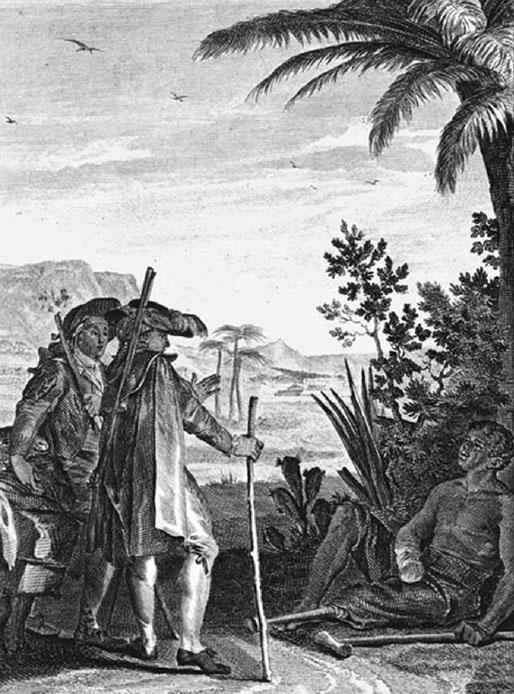

A somber encounter between the main character of Voltaire’s Candide (1788) and a mutilated slave could be considered the most powerful and important scene of the literary masterpiece:

As they drew near to the city, they came across a negro stretched out on the ground, with no more than half of his clothes left, which is to say a pair of blue canvas drawers; the poor man had no left leg and no right hand.

‘Good God!’ said Candide to him in Dutch. ‘What are you doing there, my friend, in such a deplorable state?’

‘I am waiting for my master, Monsieur Vanderdendur, the well-known merchant,’ answered the negro.

‘And was it Monsieur Vanderdendur,’ said Candide, ‘who treated you like this?’

‘Yes, Monsieur,’ said the negro, ‘it is the custom. Twice a year we are given a pair of blue canvas drawers, and this is our only clothing. When we work in the sugar-mills and get a finger caught in the machinery, they cut off the hand; but if we try to run away, they cut off a leg: I have found myself in both situations. It is the price we pay for the sugar you eat in Europe. Yet when my mother sold me for ten Patagonian écus [Spanish American coins] on the coast of Guinea, she told me: “My child, give thanks to our fetishes [sacred objects worshiped in tribal societies], and worship them always, for they will make your life happy; you have the honour to be a slave to our white masters, and therefore you are making the fortune of your father and mother.” Alas! I don’t know if I made their fortune, but they certainly didn’t make mine. Dogs, monkeys and parrots are a thousand times less miserable than we are; the Dutch fetishes [a reference to Protestant missionaries] who converted me to their religion tell me every Sunday that we are all children of Adam, whites and blacks alike. I am no genealogist; but if these preachers are telling the truth, then we are all second cousins. In which case you must admit that no one could treat his relatives more horribly than this.’

‘Oh Pangloss! [addressing his absent mentor]’ cried Candide. ‘This is one abomination you could not have anticipated, and I fear it has finally done for me: I am giving up on your Optimism after all.’

‘What is Optimism?” asked Cacambo

‘Alas!’ said Candide, ‘it is the mania for insisting that all is well when all is by no means well.’ And he wept as he looked down at his negro, and was still weeping as he entered Surinam.1Voltaire, Candide, or Optimism, trans. Michael Wood (London, United Kingdom: Penguin Classics, 2005), 51.

The conditions of slavery were so cruel that Voltaire thought it inappropriate to use his typical dark humor found in other scenes where, for example, Candide gets human excrement dumped on his head or the old woman has one of her buttocks cut off and eaten. Here we can detect the growing uneasiness many felt about the ‘triangular trade’ where Europeans imported Africans into the Americas (note the involvement of three continents). The death rate of slaves packed on ships on the infamous Middle Passage was as high as 10% during the 1700s. And that was seen as an improvement from the previous century’s 25% death rate, though the intended benefit was only to protect owners and investors from losing their investment in human cargo.

Before attempting to understand the racial aspect of the above scene, one must clarify the curious usage of a possessive pronoun which often creates confusion for readers: “his negro” (son negre). Is that a degrading choice of words? It would be illogical to draw the conclusion that the author was referring to the slave as Candide’s property because he had just met him, and Candide called him earlier “my friend.” Also Candide at the end is weeping in response to the effects of the black man being used as a commodity which contradicts the “human property” interpretation. Another possessive pronoun which was used in the same paragraph could help the reader understand: Candide renounced, and distanced himself from his mentor’s worldview by saying “your optimism.” That’s a possibly a deliberate contrast to the narrator’s reference to the slave as “his negro,” implying an affinity Candide felt towards the slave, as in “his brother.” Modern slang offers another example as when someone calls a male friend “my man.”

One unfortunate revelation from the slave delivers a coup de grâce to any faith in humanity Candide might still have left after all the ordeals he had experienced on his travels: the slave’s mother sold him into slavery. She also believed it was an honor to be a slave to the White masters. It’s true that many slaves were indoctrinated into happy subservience, however the plot device of child-selling, while it serves the narrative, is historically unsubstantiated. It was extremely rare that African mothers sell their own children into slavery, but in those rare cases when it happened it was often the result of severe impoverishment and the parents’ desire to provide the child with a better life where they’d be clothed, fed and looked after.

What the slave describes regarding his conditions is based on reality. In fact, an informed reader could find a hidden satirical message aimed at the French decree called Code Noir (Black Code), established by King Louis XIV in 1685. It was meant to regulate slavery and paradoxically protect the rights of slaves. Even though this scene, partially inspired by the French laws, is taking place in a Dutch colony, French colonies were no different. In fact, conditions were probably much worse than described here in the real Dutch colony of Surinam, which was widely known for its especially brutal treatment of slaves and their high mortality rate.

The historical document, Code Noir, is consistent with the slave’s description, which legally sanctioned punishments for delinquent slaves using amputations, hot-iron branding and executions. For example, slaves who attempted to escape would have their ears cut off based on the Code. All slaves were converted to Catholicism in French territories and they received only two sets of clothes annually. An old debate in Europe was concerning slaves’ nature and whether they were considered human or not. If they were to be categorized with animals, well, how to reconcile that with them being Christian after baptizing them (“brothers and sisters in Christ”)? The slave raises that particular point in his conversation with Candide.

What do we learn about Voltaire’s views on race and slavery from this scene?

His views on that matter were complex. Three main propositions could be presented here:

1) Voltaire intended this scene to be a condemnation of only certain practices in the slave trade and the shortcomings of the law (Code Noir, in particular) while he thought slavery was a fact of life. OR

2) Voltaire was against the entire institution of slavery yet he still believed in racial inequality. OR

3) Voltaire was a proto-abolitionist calling for universal equality between all the races as we understand it today.

Although there’s some supporting evidence for the first choice, most likely the truth is between the first and the second option.

Here is the supporting evidence for the first option: Candide encounters other characters on his journeys, white Europeans and South American indigenous peoples, who were also enslaved for periods of time and while their misery is highlighted we don’t detect a hint of condemnation by the author of the practice. (It should be emphasized that slavery of other ethnicities pales in ruthlessness to that experienced by Africans throughout history.) That demonstrates that when Candide is moved to tears, it’s not because he saw a slave, but because of the tragic conditions under which he found him.

Yet there’s evidence for the second option demonstrating that Voltaire was critical of the entire slavery system which could be found in a memorable statement by the slave: It is the price we pay for the sugar you eat in Europe. The French thinker, through the slave’s words, criticized European societies which benefited from injustice while they thrived on luxurious commodities like sugar, coffee, cocoa, tobacco and cotton.

Although Voltaire was not unique in highlighting the misery of slaves through literature, non-fiction books and articles, he went further than most writers of his era and became one of the the earliest critics of slavery and European colonialism. However it would be unreasonable to expect an eighteenth-century Enlightenment intellectual to denounce slavery in the same passion, or language as a twentieth-century liberal. Regardless of his exact stance on slavery, Voltaire was a radical by the standards of his time in depicting a white European man calling a slave “my friend.” He was a radical in using the familiar character of the noble savage and giving him a voice and enough knowledge to be able to criticize colonialism and slavery eloquently.

You might also like:

Candide: The shocking passages

Condemned by the French government and the Catholic Church: Read the controversial passages from Voltaire’s Candide (1759)

BOOK: CANDIDE

Why Voltaire mocked Canada as ‘a few acres of snow’?

He also called it the land of ‘barbarians, bears and beavers’

BOOK: CANDIDE

Endnotes