How was one of the most tyrannical political systems in history inspired by an art movement?

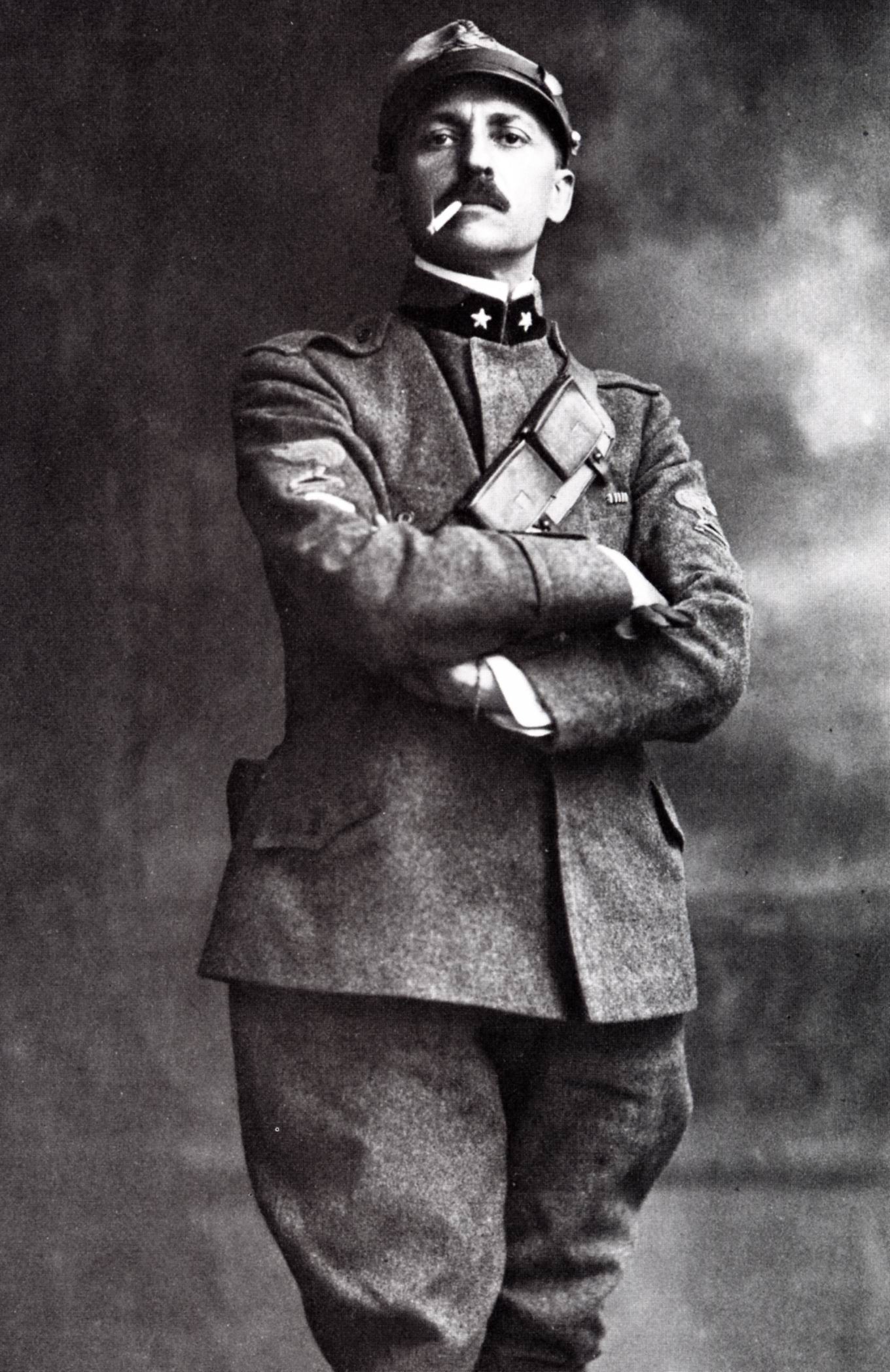

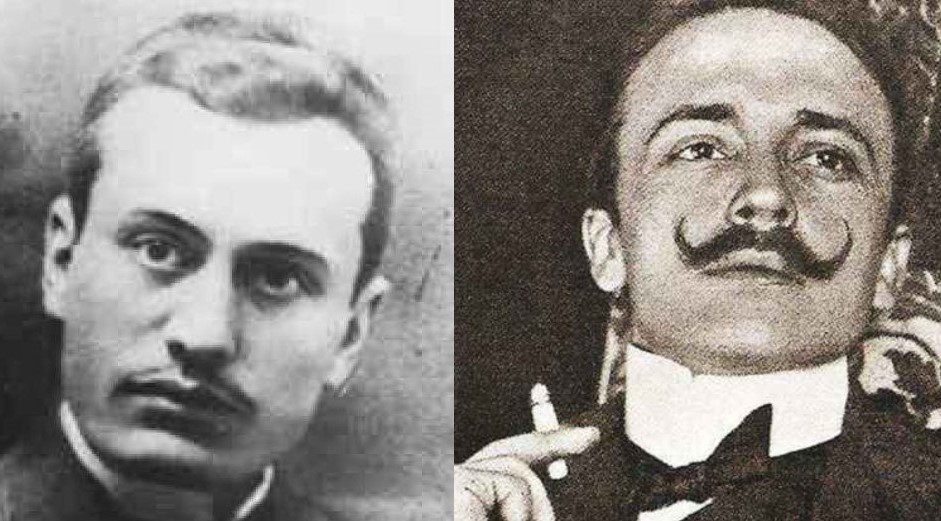

Those who understand history of the last century know that fascism was born in Italy, just after World War I. But who laid the foundations of that ideology? While Mussolini, the would-be fascist dictator, was actually an important socialist revolutionary, someone else was spreading proto-fascist ideas, under the name of Futurism, founded by F. T. Marinetti. Strangely, some recent writers and bloggers like to present evidence that the ideologue never meant his ideas to be what they represented under Mussolini. Some respectable writers have twisted Marinetti’s story to dissociate it from fascism by claiming that his statements were misunderstood or metaphorical. Another often-mentioned fact is that he resigned from the fascist party in 1920.

The reality is Marinetti was officially a founding member of the Italian fascist party and, despite formally quitting, his allegiance to Mussolini, and the state, continued for the rest of his life. This article will not explore the official relations between the poet and the dictator, Marinetti and Mussolini. (Read a timeline of the Fascist-Futurist alliance here.) What I wish to demonstrate below is deeper than collaboration: It’s how early ideas by the founder of Italian Futurism match most of the typical characteristics of 20th-century fascism that was yet to emerge. Indeed, I present here the evidence that Futurism was proto-fascism.

Note: The list below of common characteristics of Fascism is based on the work published by political scientist, Laurence W. Britt.

As shown above, a total of 14 features of fascism were originally theorized in Futurism, starting with two of high importance: extreme nationalism and glorification of war. Also, at the end of this article I demonstrate that manipulation of religion appeared only later in fascism, but in its early days, like Futurism, the dominant attitude was anti-clerical and anti-Church. However the Futurists never supported establishing secret police or framed the national revival as a return to a lost golden age (the Roman Empire), unlike the fascists.

A note regarding quotations used here: The founding document of Italian Futurism, published as early as 1909, contains in a concise form all the important elements of fascism which would be founded as a political organization six years later. However, this article uses, beyond a few excerpts from the manifesto, longer quotations by the founder, F. T. Marinetti, from his other articles and interviews for a more detailed insight.

Ask a friend to define fascism and most likely they will struggle. A curious fact about one of the most evil political systems to appear in modern times is that there is no clear or standard definition for it. But if there is two words to sum up fascism, then they would be “extreme nationalism.” That is the one criterion by which we could judge a regime as such. Extreme nationalism starts with patriotic slogans, symbols and songs. That path of “borderline worship” of the state leads to accusing political opponents of being “traitors.” A fascist regime displays distrust of all things foreign. Xenophobia becomes rampant among the public. These were the ideas that F.T. Marinetti had been preaching since as early as 1909 before he created a political party in 1919. In a manifesto published in 1913 titled Futurist Political Program, he described his vision:

Italy, absolute and sovereign. The word ITALY must predominate over the word LIBERTY.

All freedoms must prevail other than those of being cowardly, pacifist, or anti-Italian.

A bigger fleet and a bigger army; a people proud to be Italian, in favor of war, the sole cleanser of the world, and of an Italy that is intensely agrarian, industrialized, and commercialized.

Economic protection and patriotic education for the proletariat.

A foreign policy that is self-interested, shrewd, and aggressive—colonial expansion—free trade.

Irredentism—Pan-Italianism—the supremacy of Italy.1F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 75.

These words were written an entire year before Mussolini established the first fascist organization. In fact, Mussolini was officially a socialist at that point.

The Futurists gave rise to proto-fascist ideas which would make the central philosophy of an Italian generation seeking to build a political movement. They became known as fascists, the first such group in the world. Later, that ideology crossed borderlines, from Italy, where the first fascist government took power, into countries like Hitler’s Germany, Franco’s Spain and Salazar’s Portugal. Fascist parties appeared in the following decades as far as Japan, Argentina and Lebanon. So, the Futurist influence on modern history is more than we realize or, perhaps, would like to realize.

Although ideas like the glorification of war or ultra-nationalism were not “invented” by the Futurists, they were the first to build a real movement based on them. They made it clear that Futurism is not like any preceding art movement. Theirs was overtly political. They popularized their beliefs through organized propaganda efforts; through manifestos, paintings, interviews and evening gatherings. In reality, the Futurists shared a number of ideas with socialists and anarchists. For example, they supported the abolition of the police (explained below) as the anarchists did. With the Socialists in particular, the enemies of the Futurists, they had much in common. Both groups were:

– Against bourgeois values and cultural institutions including marriage

– Demanding more rights for women and the advent of free love

– Anti-clerical and anti-Church

– Supportive of a revolutionary change and welcomed violence as a necessary means

Regarding the extreme version of patriotism that was preached by the Futurists, and later by the Fascists, it is best viewed as a product of its time: A generation of Italians growing up seeing their home country as a hot spot of corruption, poverty, crime and disease. They had no hope that the ancient Catholic Church could restore order. To a certain degree, the Church was also responsible. In their eyes, their only hope was an ultra-nationalist government with an iron fist.

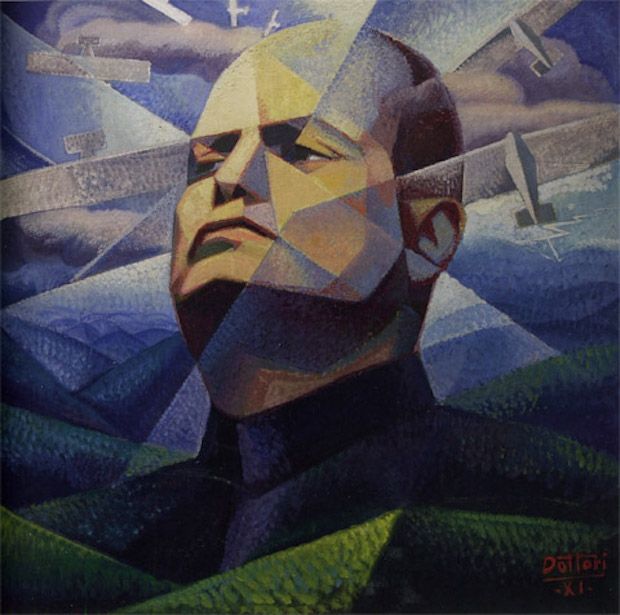

2. Militarism: Glorification of the military

Militarism is about the importance of the military in a fascist society. From the paramilitary uniforms to the salutes, we see signs of the celebration of the military everywhere. Members of the military are given prestige unmatched in the civil society. Virtues, often associated with military service, are preached to the entire society such as discipline, obedience, physical fitness and unquestioning respect of the authorities. One’s patriotism is determined by one’s opinion of the military. Marinetti wrote in 1910…

We revere patriotism and militarism, our song is war, sole cleanser of the world.2Ibid., 161.

Even if the nation is struggling with resources, a lion’s share of funding goes to military institutions. Militaristic solutions are the first resort in dealing with problems, domestic or overseas. That often leads to wars of aggression and territorial expansionism. The Futurist founder welcomed such rivalry:

[T]he industrial and military rivalries that develop between different nations are a necessary factor in human progress.3Ibid., 61.

3. Glorification of violence and its use for political purposes

Fascists considered violence as a force permissible by their supporters against their opponents. Mussolini’s blackshirts and Hitler’s brownshirts used similar tactics to suppress dissent. Praise for violence, as a force to purge society from “the enemy,” goes back to Futurist writings:

Blood, you should know, has neither value nor splendor unless it is liberated from its imprisonment in the arteries, by iron or by fire! And we shall teach the armed soldiers on Earth how their blood should be spilled… But first of all we have to clean out the great barracks where you insects are swarming!… It won’t take long… but for the time being, you lice can go back once more, for tonight anyway, to your filthy beds of tradition which we no longer wish to sleep in! 4Ibid., 24.

Marinetti wrote these words at the end of the first decade of the twentieth-century. The title was Let’s Kill Off the Moonlight. His brutal language was not aimed at real people but those who represent traditions (moonlight) in the realms of art and culture. Being a poet, he wrote it in the form of prose, i.e. his call for violence above should not be taken literally. But even though the above text is metaphorical, it still shows the Futurist fascination with violence from its very start:

Art, indeed, can be nothing but violence, cruelty, and injustice. 5Ibid., 16.

In a speech in Naples, in 1910, he spoke of the necessity and the beauty of violence:

From a clear love of danger, from habitual courage and from everyday heroism spring precisely—and naturally—an urgent need for and recognition of the beauty of violence. 6Ibid., 60.

Three years later, in 1913, Marinetti described his brand of nationalism in an open letter:

[W]e profess an ultra-violent nationalism, anticlerical and antisocialist, a nationalism opposed to tradition and based on the inexhaustible vigor of Italian blood. 7Ibid., 105.

The Futurists supported the violent attacks—assassinations and bombs—by members of the anarchist movement.

[W]e can reconcile the glorification of patriotism and the exaltation of the anarchists’ acts of destruction.

At the time of writing, anarchists had been launching attacks for half a century around Europe. The infamous “Propaganda of the deed” was the name of the action they take against certain figures or property in hopes of instigating a major political change. Marinetti admired their tactics:

Speaking personally, I much prefer the anarchist’s bomb to the cringing attitude of the bourgeois, who hides away in a moment of danger, or to the vile egoism of the peasant, who deliberately injures himself rather than serve his country.

Marinetti above is referring to the bomb thrown by the French anarchist, Auguste Vaillant, in the Chamber of Deputies in 1893. There were no fatalities but he was guillotined.

That was the Futurist attitude towards violence in a general sense, or specifically against internal enemies. Next section is what he had to say about war and external enemies.

4. War as a means of national rejuvenation

In 1909, the the same year Marinetti published the founding document of his movement, he wrote in a preface to his Futurist novel:

Let’s glorify war! 8Ibid., 33.

Also it was the same productive year when he wrote the warmongering prose (mentioned above) fantasizing about his Futurist “clique” in a real battle against the “cowardly” traditionalists. His words were morbid:

[W]e could use up all our ammunition, growing old in the slaughter!… Let me adjust my sights!… Raising to eight hundred meters!… Ready!… Fire!… Oh what ecstasy, playing skittles with Death!… And that’s something you cannot take away from us! 9Ibid., 31.

In an interview with a French magazine in 1909, he explained:

I believe that a people has to pursue a continuous hygiene of heroism and every century take a glorious shower of blood. 10Ibid., 19.

One phrase from 1910 captured the spirit of Marinetti’s war-themed speeches and theatrical performances:

We shall go to war singing and dancing! 11Ibid., 158.

Under the title War, the Sole Cleanser of the World, published in 1911, he gave his view on peace:

We consider the hypothesis of the friendly unification of peoples to be outmoded and utterly dispensable, and we see for the world only one form of purgation, and that is war. 12Ibid., 53.

At times Marinetti described war as a “healthy exercise”, as he did in a manifesto in 1914:

This current war [World War I] is indeed the finest Futurist poem that has appeared until now. 13Ibid., 235.

At other times he spoke of it as an inspiration, or a form of art (also in the same manifesto):

We Futurists Free-Word-smiths, painters, musicians, sound makers, and architects have always seen war as the only inspiration for art, the only purifying morality, the only leaven for the dough of humanity. War alone is capable of renewing, speeding up, and sharpening human intelligence, of ventilating the brain and easing the nerves, of freeing us from our daily cares, of giving a thousand different tastes to life and a modicum of creative talent to the dumb-witted. War is the only rudder to steer us through the new age of the airplane, which we are in the process of creating. 14Ibid., 236.

As seen above, to the Futurists, war is also a modernizing force and a process of “renewal.” War, to the Futurists, is natural and unavoidable:

War cannot die, for it was one of the laws of life. Life = aggression. Universal Peace = the decrepitude and death throes of races. War = bloody and necessary trial of a people’s strength. 15Ibid., 235.

Later in that manifesto, he celebrated the potential of war to destroy “internal” enemies:

The War will root out all its enemies: diplomats, professors, philosophers, archaeologists, critics, cultural obsession, Greek, Latin, history, senility, museums, libraries, and the tourist industry. The War will foster gymnastics, sport, schools of practical agriculture, commerce, and industry. The War will rejuvenate Italy, it will enrich her with men of action, it will compel her to live no longer in the past, amid ruins and in a gentle climate, but by virtue of her own national strengths. 16Ibid., 236.

In 1915, many Italians were calling for Italy to join the Great War (WWI), which had started the previous year. Marinetti said in an interview in February 1915:

The idea of war brings us joy, it exalts us. 17Ibid., 238.

In May, as fate would have it, Marinetti and Mussolini would be arrested together for having organized “interventionist” protests demanding that Italy joins the war. They would be granted their wish the same month of May of 1915. In an essay that Marinetti wrote while in prison, he wrote:

Relative peace is nothing more than a breathing space to get over the exhaustion of the last war or the last revolution. Absolute peace will prevail perhaps only after the human race has disappeared altogether. 18Ibid., 342.

Marinetti later took glorification of war to a maniacal level. In July 1917, he created a choreography influenced by the events of battle. The dances were symbolic of man-machine fusion, where their designer intended to celebrate not only war but also the new technologies that allow it to be vicious. The first is called Dance of the Shrapnel:

I wish to represent the fusion of the mountain with the trajectory of the shrapnel. The fusion of human song with the mechanical sound of shrapnel. To present an ideal synthesis of war: a solider from the Alpine regiment singing, without care in the world, beneath an unremitting vault of shrapnel shells. 19Ibid., 211.

The other one is Dance of the Machine Gun. He presents it in the following dark words:

I want to present the naked, human quality of the Italian cry of Savoy! [Battle cry similar to “Forward!”] as it is ripped apart and dies heroically in shreds, against the mechanistic, geometrical, and inexorable stream of machine-gun fire.20Ibid., 214.

After many years of warmongering, the Futurists finally saw an opportunity for a war. They became the first voices to call for Italy to join the Great War. Italy joined that “war to end all wars,” which had started in 1914, the following year: 1915. The Futurists rushed to the front lines. The war took the lives of 600,000 Italians. Several Futurists did not survive the war, either due to serious injury or due to circumstances around the war. The most famous Futurists who got killed were the artist Umberto Boccioni and the brilliant architect Antonio Sant’Elia. Even Marinetti himself was injured and hospitalized in May 1917. That did not prevent him from advertising, two months later, the “beauty” of war and spreading military propaganda on assignments from the Italian generals:

The Great War is tearing the cemeteries apart with its bombardments; it is overturning all romantic solitariness and plowing it in, with its bombardments; it is decapitating the mountains with its bombardments; it is turning the dead cities upside down with its bombardments, freeing them and stimulating them into new life; it strides over monuments and cathedrals and overturns them. 21Ibid., 245.

5. Imperialism: Support for territorial expansionism

The Futurists showed enthusiasm for expanding Italian territory, by the ruling nationalist government, long before the fascists in the mid-1930s took over Ethiopia. (Hitler would have similar expansionist ambitions towards east Europe.) In fact, the Futurist support for colonial battles goes back to two decades earlier when Italy arrived late in the game of the so-called “scramble for Africa” (from 1881 to 1914). Other European powers were not interested in Libya, so Italy was grabbed that “reject” territory which itself was under the weak Ottoman Empire. Many political parties were opposed to the perilous adventure across the Mediterranean for an economically-struggling nation. However, among the first to support Italian colonialism were the Futurists. Early on, in 1911, Marinetti traveled to Libya to show his support and stayed to work as a war correspondent observing the the Italian-Turkish battles over the Libyan land. The Italo-Turkish War would last from September 1911 to October 1912. In a 1913 speech in Florence, and to cries of support from his audience Marinetti stated his views on the colonization of Libya:

I consider all anti-Libyan socialists, republicans, and radicals to be miserable scum. Equally scum are the liberals and conservatives who are not able to defend themselves and duly glorify the colonization of Libya. (Cries of “Long Live Libya! Up with the war!”) 22Ibid., 177.

He ended the speech with commitment to do whatever it might take to keep hold of Libya while destroying the Libyan resistance:

Every endeavor, therefore, and all necessary money, brutality, and blood for the vigorous, practical completion of this Libyan exploit. This completion is today the colonial Futurism of Italy. I end with the cry “Libya Forever!” 23Ibid.

In a 1914 manifesto, Marinetti wrote:

For a nation that is poor, yet prolific, war is a business, namely the acquisition of the lands that it lacks, by virtue of the superfluity of its blood. 24Ibid., 236.

Mussolini after he seizes the leadership of the Italian government in 1922, he would step up the military campaigns to crush the Libyan resistance. In his mind, Libya’s takeover could be part of the Roman Empire’s ancient possession which “rightfully” belonged to Italians. His behavior and statements betrayed a fantasy of seeing in himself a new Julius Caesar. He had visions of sending poor Italians to take over agricultural land, thereby reducing their burden on his government. Libya could even become the bread basket for Italy like it was in the ancient times. The vision never materialized. A treaty would end the brutal imperialist campaign two years after the fall of the fascist government in 1947.

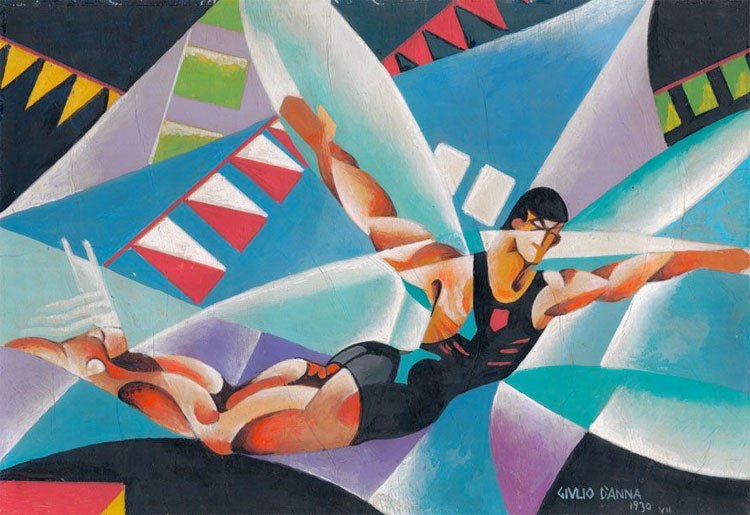

6. Fetishization of masculinity and blatant misogyny

Fascism is a masculine movement, fascinated with violence and adoring of military virtues. Not only were the governments male-dominated but women in general were seen as a potential threat to manhood. Such narrow-minded views of women were not unique to fascists nor new under their rule, however they solidified these ideas in the national culture. The Futurists arrived on the cultural scene with a manifesto that was shocking in its misogyny. It advertised their “scorn for women.” The cruel words were shocking and Marinetti for years later was questioned for what he meant. Their “futuristic” vision clearly had no room for women:

Yes, our sinews insist on war and scorn for women, for we fear their supplicating arms being wrapped around our legs, the morning of our setting forth!…What claim do women have on us, or for that matter, any of the stay-at-homes, the cripples, the sick, and all the caution-mongers? 25Ibid., 23.

On the other hand, the Futurists glorified masculinity. They used gendered discourse to describe the future. The masculine is aggressive, rapid, heroic and modern. The feminine is weak, passive, slow and traditional. That explains their declaration of “scorn” in their manifesto. Elsewhere in the founding manifesto, masculinity is represented by their “love of danger”:

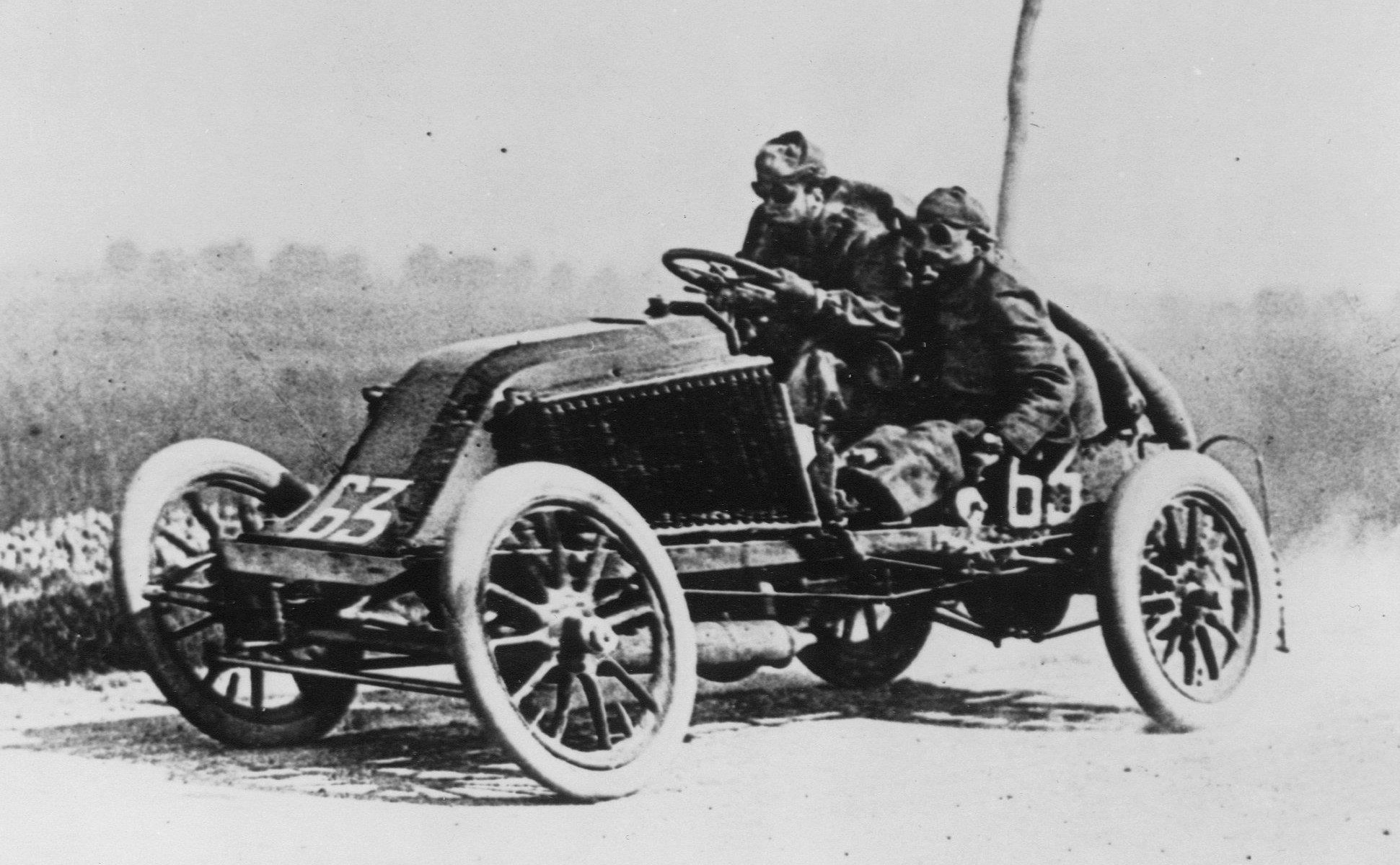

We wish to sing the praises of the man behind the steering wheel, whose sleek shaft traverses the Earth, which itself is hurtling at breakneck speed along the racetrack of its orbit. (p. 13)

In the Futurist world, men are heroes, and heroes are men:

Heroism as an everyday occurrence. Every kind of danger and every kind of struggle. Hands dirty from digging trenches but equally adept with the pen, the rudder, the steering wheel, the chisel, the slap in the face, and the rifle. 26Ibid., 239.

Seeing women as a danger, he proposed separating little boys from girls:

And that mixing of males with females at a very early age, which is the cause of a harmful effeminacy in the male, will be abolished once and for all.

Male children—in our opinion—must develop separately from little girls, so that their early games are unequivocally masculine, which is to say, totally devoid of all cloying affections, of all womanish refinements. They must be lively, combative, muscular, and violently dynamic. 27Ibid., 311.

It is not surprising that he was opposed to women joining politics, accusing them of being naturally passive and pacifist:

It is very apparent that a government composed of women or one supported by women would drag us fatally down the road of pacifism and Tolstoyan cowardice. 28Ibid., 57.

Fascists understood that the one group who possess physical strength, propensity for violence, readiness for combat and revolutionary fervor are young men. Hence their message targeted the youth first and foremost. Fascists also knew that they could exploit the idealism of youth for their movement. Long before fascists viewed older people as an obstacle, Futurists did so:

[A]s far as the great Futurist hope is concerned, all authority, all rights, and all powers will be violently torn from the hands of the dead and the dying and given to young people between twenty and forty years of age. 29Ibid., 84.

The Futurist obsession with youth is best summarized in the following outlandish statement by Marinetti:

I glorify violent Death, which is the crown of youth. Death which gathers us in whenever we are worthy of her immortalizing voluptuousness!… Woe betide any man who lets his body grow old and his spirit wither! 30Ibid., 40.

One could say that the Futurist movement mixing themes of technology, speed, youth and violence foreshadowed our contemporary pop culture.

We wish to spur young people toward the most impertinent of intellectual vandalisms, so that they live with a taste for madness, a craving for danger, and a hatred for all those who counsel caution.

We wish to prepare the way for a generation of strong, muscular poets who know how to develop their courageous bodies, every bit as much as their vibrant spirits. 31Ibid., 20.

“Strong, muscular poets” is a fascinating description of perhaps the new Futurist man, who would be perfect in every aspect. More on that in the next section.

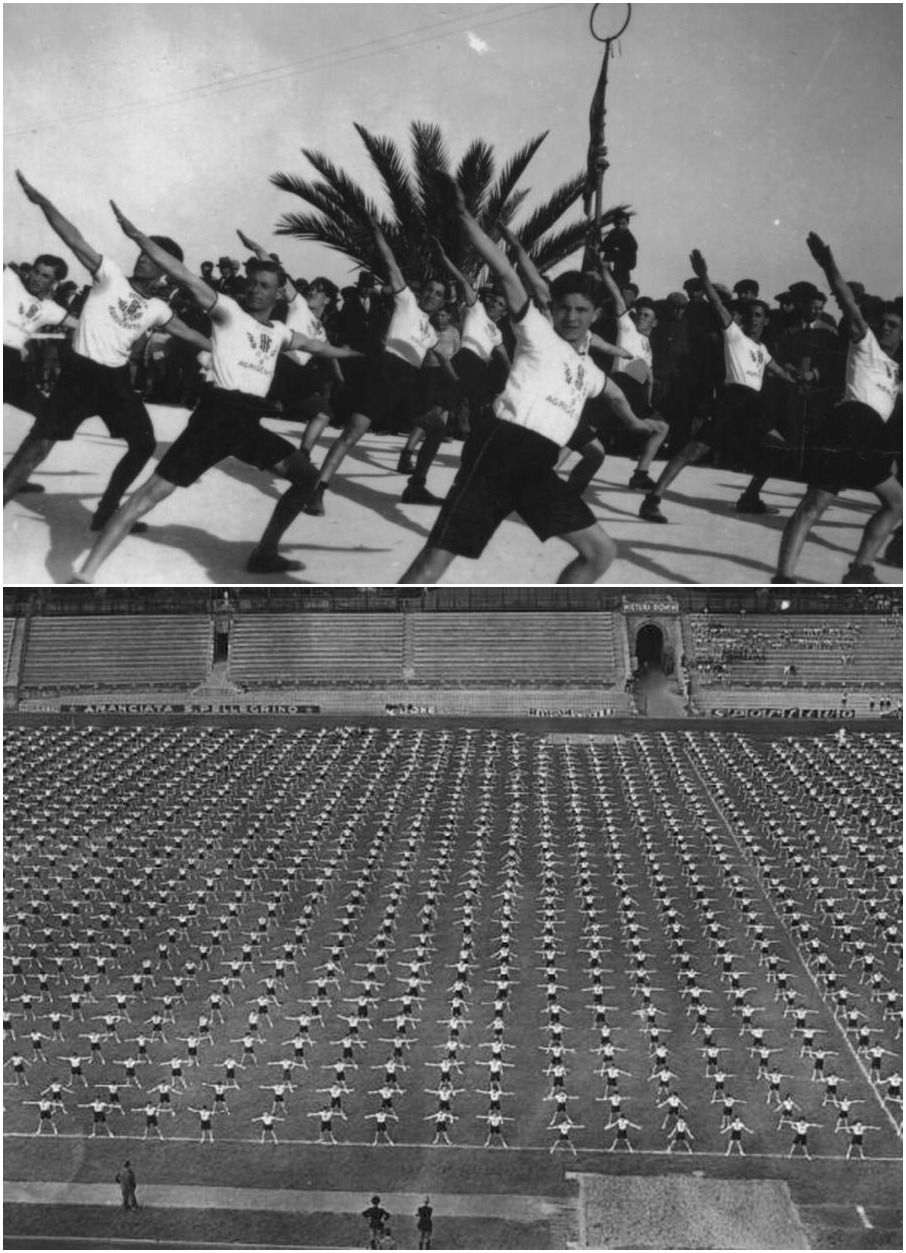

8. Building the “new man”: Education as character building

Under fascist regimes, the purpose of education was to create the model citizen, the solder-citizen. Teachers, on behalf of the state, help transform children into “instruments” to serve the state and follow authority, no matter the political or military demands. The “Futurist man” preceded the “fascist man” but would display the same values and endure the same rigorous training. Youth under a futurist, or a fascist, government are disciplined and physically strong.

Everyday, in the joy of life in the open air, with games taking absolute precedence over books, we have to talk about the divinity of Italy to the children of Italy, to persist in teaching them about physical courage and scorn for danger, always rewarding fearless daring and heroism.

The schools for physical courage and patriotism must replace the courses in Greek and Latin, which are suitable only for prehistoric cavemen. 32Ibid., 74.

More than a decade before the German organization, Youth League of the Nazi Party, was founded (later renamed Hitler Youth), Marinetti recommended giving children similar paramilitary training:

What would you say, for example, about that Futurist plan to introduce a mainline course in risk-taking and physical danger into all our schools? Regardless of their own wishes, the pupils would be subjected to the necessity of continually confronting a series of dangers, each one more fearsome than the last, skillfully arranged and always unforeseen, such as fires, drowning, the collapse of a ceiling or other like disasters… 33Ibid., 83.

The training deliberately ignores the intellectual development of children and instead breeds warriors, ready to carry out their duty even if it means fighting a gruesome war. During the second world war, the fascist man’s obedience was put to the test when he carried out orders of “exterminating” innocent citizens deemed enemies by his government.

To appeal to young men, fascists presented their political movement as a revolutionary one. They displayed their enthusiasm in parades, rallies and mass meetings. All of that goes back to Futurism. Marinetti wrote as part of the Futurist Manifesto, which was published on the front page of Le Figaro in 1909:

It is from Italy that we hurl at the whole world this utterly violent, inflammatory manifesto of ours, with which today we are founding “Futurism.” 34Ibid., 14.

Years later, members of the movement would establish a political party. In 1929, under the title of An Artistic Movement Creates a Political Party, Marinetti wrote:

Unique in history our Party [is] utterly devoid of rhetoric, violently Italian, and violently revolutionary, free, dynamic, and armed with tactics that are entirely practical. 35Ibid., 277.

10. Opposition to liberalism and disdain for the doctrine of human rights

Fascist regimes viewed with suspicion liberalism which historically laid the basis for principles such as human rights, democracy, equality before the law and freedom of speech. Humans rights were viewed by fascists as an obstacle in the path of the state. Fascists were not unique in their rejection of liberalism:

In the name of our Futurist originality, we reject the common notion that the words “democracy,” “freedom,” “justice,” “feminism,” and so on, are formulas that can simply be applied universally. 36Ibid., 347.

Fascists, and the Futurists before them, did not officially reject the principle of civic rights, but reserved the right to define it according to their purposes, to protect the nation from the “decadent” elements. Fascists used propaganda to win popular support for their campaigns of killing, summary executions and incarcerations without trials. Marinetti summed up the Futurist view of individual liberties in one sentence:

All liberties and all progress within the great circle of the Nation! 37Ibid., 161.

11. Disdain for intellectuals and artists (populism and anti-intellectualism)

Fascists suppressed freedom of expression in art and higher education. The only art that was allowed to exist was the political kind that served the national agenda, usually called populist art. The Futurists were unique in that sense, that they were a group of artists with a political agenda. Although, they did not call for the suppression of other artists, they often expressed hostility towards them. They attacked the Pre-Raphaelites, Romantics and also Symbolists. They considered them “decadent” artists who have no modern vision nor a solution for society’s problems. Marinetti described a Futurist as…

Anyone who loathes ruins, museums, cemeteries, libraries, cultural snobbery, the authority of professors, academicism, imitation of the past, purisms, matters long drawn out, and punctiliousness. 38Ibid., 368.

Marinetti famously called for the destruction of museums and libraries:

Come on then! Set fire to the library shelves!… Divert the canals so they can flood the museums!… Oh, what a pleasure it is to see those revered old canvases, washed out and tattered, drifting away in the water! 39Ibid., 15.

Also, Fascist governments distrusted professors and other academics for their unorthodox ideas and their potential expression of dissent. Under fascism, professors were arrested and even executed. From its very foundation in 1909, right in its manifesto, Futurism declared war on academia calling them a “cancer”:

[W]e wish to free our country from the fetid cancer of professors, archaeologists, tour guides, and antiquarians. 40Ibid., 14.

Ideal professors are ones who join the political program of building the “new man,” as explained above, that is a strong and disciplined soldier. So even professors who are not dissidents, yet won’t join the state educational program of “rebuilding” children into model citizens are of no use to the state. Marinetti’s anti-intellectualism went as far as calling for the shutting down of “useless universities”:

The abolition of many useless universities and of classical education. Obligatory technical instruction in the workplace. Obligatory and legally enforced technical gymnastics, sport, and military education in the open air. Schools promoting courage and the Italian spirit. 41Ibid., 271.

Similar ideas were formulated clearly in their Futurist Political Program:

A cult of progress and speed, of sport, of physical strength, of fearless courage, of heroism, and of danger, against any obsession with culture, classical education, the museum, the library, and archaeological remains. The suppression of Academies and Conservatories.

Many practical schools for commerce, industry, and agriculture. Many institutes for physical education. Gymnastics in schools every day. Supremacy of gymnastics over books. 42Ibid., 76.

In an interview with an Italian newspaper in 1915, he described the Italy of the future as…

[A]n Italy without professors, without archaeologists, with few lawyers, very few doctors, life in the open air, gymnastics, sports, fewer disputations and more punches. Instinct, muscles, fewer armchairs and no slippers! (p. 241)

“And jackboots for every young man,” he might as well have added!

Perhaps the most shocking statement Marinetti pronounced against academia was in his 1910 one-page pamphlet titled Contro i professori (Against Academic Teachers) where he defended the murder of a teacher by a student as a heroic act. Only days earlier, on May 18, a murder had captivated the public: a 14-year-old student, Riccardo Li Donni, in Palermo, protested his bad grades with his teacher of literature, Camillo Ghelli. The teacher rejected his pleas for a review. The young student pulled out a gun, in front of other classmates, killed his teacher then shot himself in the head. The public response ranged from indignation to pity. Marinetti’s comment on the crime:

As the world has need of nothing but heroism, then excuse—as we do—the bloody act of indiscipline carried out by the Palermo student Lidonni, who, regardless of the law, avenged himself on a tyrannical teacher. Tyrannical teachers were entirely to blame for this death. Traditionalist teachers, whose wish is to drown the irrepressible energies of young Italians in their stinking, subterranean sewers. When, oh when, will they leave off emasculating those spirits which must create the future? 43Ibid., 84.

12. Opposition to parliamentary democracy

Parliamentary democracy is too weak, in the eyes of fascists. It allows for internal threats to exist. Fascists also saw it as a system that allows democratic inclusiveness and power to those who can not rule themselves. However, fascists in Italy, Germany and elsewhere played the electoral game to reach the top, though their dislike for democracy was never clandestine. The Futurists were also absolutely against parliamentarianism:

Almost all European parliaments are nothing more than noisy henhouses, stalls, or sewers. 44Ibid., 56.

In 1910, Marinetti expected the parliamentarian system to crumble:

I believe that parliamentarianism, a political institution that is both unsound and frail, is inevitably destined to perish. 45Ibid., 63.

Years later, in 1918, when it was clear that it was not on the brink of collapse, Marinetti urged in his Manifesto of the Futurist Political Party for forcefully disbanding Parliament and replacing it with a select few (a technocratic council):

If this rational and practical Parliament fails to yield positive results, we shall abolish it altogether and bring in a technocratic government without parliament, a government composed of twenty technocrats elected by universal suffrage. 46Ibid., 272.

Elsewhere he elaborated who these technocrats might be:

[I]ndustrialists, agrarians, engineers, and businessmen in the government of the country. 47Ibid., 271.

He said in a speech to the Fascist Congress of Florence:

The Technocratic Council, which will replace the Senate, should therefore be made up of very young men, men who have not yet reached thirty. 48Ibid., 332.

Although, the Futurists did not advocate dictatorships, their contempt for parliamentary democracy paved the way for fascist dictatorships.

13. Opposition to socialism and communism

Both fascism and socialism were violent, totalitarian mass movements which emerged largely in the turmoil following World War I. But they had a history of hostility throughout the twentieth-century. Fascists promised to be more brutal against socialists unlike the democratic regimes preceding them. Under the fascist rule, socialists were sent to concentration camps and many were killed. Italian fascists sent armed squads to intimidate factory workers on strikes. Nazis unleashed paramilitary units onto “red” neighborhoods.

One of the reasons a fascist, who’s naturally ultra-nationalist, views Marxists of all stripes as traitors is their allegiance to an international working class. Futurists harbored a similar sentiment as shown below in the quote where Marinetti emphasizes that his movement is a genuinely Italian one unlike socialism, a foreign ideology to Italy:

[W]e Italian creators are ill-disposed to taking orders from anyone, or to aping the Russian Lenin, disciple of the German Marx. 49Ibid., 339.

The Futurists detested socialism since they, for several decades and through World War I, were opposed to war. (The socialist view: If “workers of the world unite,” then why join the bourgeois wars?!) Marinetti accused them of hypocrisy:

They declare that the war should have been avoided at all costs, yet recognize (in lowered voices) that the development of the revolutionary socialism is one of the fruits of the war. 50Ibid., 345.

In that regard, he looked down on them as cowardly pacifists, while his own movement was the revolutionary one in its support of war:

Not only are we more revolutionary than you, the official socialists, but we have gone way beyond our revolution. 51Ibid., 346.

Meanwhile Marinetti probably had deep admiration for the bloody Bolshevik revolution against the old Tsarist system. He expressed some sympathy for their movement:

The Russian Revolution has its own justification in Russia and can only be judged by Russians; it cannot be imported into Italy. 52Ibid., 344.

He also acknowledged that among the Russian revolutionaries there were several Futurists, inspired by his Italian movement. In a fascinating historical irony, it was only to communist Russia that one could say the Italian Futurist art movement was successfully exported:

I want to make all that clear so that my judgement on the Russian Futurists may appear absolutely and objectively fair. I am pleased to learn that the Russian Futurists are all Bolsheviks and that Futurist art was, for some time, State art in Russia. The Russian cities were decorated by Futurist painters for the last festival in May. 53Ibid., 345.

14. Scape-goats as a unifying cause: A struggle against social “decadence”

The idea that the iron-fisted fascists will rescue a “decadent” society was a justification for many of their brutality against their opponents or whom they considered “unfit.” The decadents included bohemians, communists, feminists, pacifists, liberals and anyone unwilling to support them. Then there were the ones who were deemed physically unfit for their “masculine” and militant vision: homosexuals, the old, the handicapped, the mentally challenged and in generic terms, women, or even men who were physically or mentally “fragile.” That umbrella of decadence was extended to also some ethnic minorities, who perished under their rule, like Jews and the Roma people (Gypsies). The idea of saving a society in decline goes back to the Futurist movement. Here is how Marinetti described Futurism in an interview in 1915:

Bold, continuous progress; abolition of the authority of the dead and the old, of the sluggards, of the cowards, of the velvet-tongued, the delicate, the effeminate, the nostalgics and the weak. Life intensified. Daily heroism. Let’s experience all dangers and all struggles. Let’s dirty our hands by digging trenches, be ready for combat, for punches, for the rift. 54Ibid., 146.

One important characteristic of fascism that is not discussed above is its aims of totalitarianism. As demonstrated here, Marineti advocated forced culture change in institutions like universities and academies. He did not explicitly advocate censorship, but to some extent, that was implicit as a by-product on the painful Futurist path of progress. In a twist of fate, under the Mussolini rule, he suffered from tight controls on cultural expression. It was during the final decade of his life, that the man who had been young, aggressive revolutionary was transformed into an old and semi-obscure pro-government writer with barely any influence. However, he did actually oppose the emergence of attacks on “degenerate art” and burning of books in the late 1930s.

As there is no anti-Semitism in Italy, we have no Jews to emancipate, consider, or pursue. (p. 344)

15. Politicization and manipulation of religion

Most of the characteristics of fascism could be directly traced to Futurism, with one exception, the role of religion in the modern state. Historically, opportunism and pragmatism won the day.

Fascism is known today for its manipulation of the public through the dominant religion. Unlike communist regimes, which were “godless,” fascists claimed to protect religion and its traditional values. They were the defenders of the faith from “the godless.” Their behavior and policies never aligned with the religious institutions they claim to be allied with, but that mattered little. The alliance was always opportunistic for both sides. It is convenient to brush any political opposition as an attack on religion. That was effective since some of the most ardent opponents were “atheist” communists.

A look at the early anti-religious writings of Futurism, or even early Italian fascism, is evidence of the opportunism and hypocrisy of the government-church alliance during the 1930s. For example, both Marinetti and Mussolini, in their younger years, were not only anti-Catholic but even called for raiding churches and for expropriating their properties by the state. If they saw the ultra-national project of fascism as a modernizing force, then the “conservative” church was an enemy. Also, the church had influence on the voters making them a competing bloc. Unlike other nations, Italy in particular being the host of the papacy, saw powerful resistance from the Church versus several progressive movements throughout its modern history. One cause which the young “forward-thinking” Italians would not forgive was the Church’s opposition to a united national government in Italy for three entire centuries (until 1871) while it was the norm in Europe. Even then, those young Italians of the early 20th century, knew that the church still did not recognize the government of Rome! (That would change with Mussolini’s Lateran Treaty of 1929.)

In the very year of 1909 when Futurism was established, the 26-year-old atheist Benito Mussolini published a semi-pornographic and anti-clerical novella called The Cardinal’s Mistress. In 1919, he called for the “de-Vaticanization” of Italy:

[T]here is only one possible revision of the law of Guarantees and that is its abolition followed by a firm invitation to his Holiness to quit Rome.

In April 1921, Mussolini in a speech in Bologna said:

Fascism is the strongest of all the heresies that strike at the doors of the churches. Tell the priests, who are more or less whimpering old maids: away with these temples that are doomed to destruction; for our triumphant heresy is destined to illuminate all brains and hearts. Make way for the youth of Italy, whose faith and passion are demanding expression.

Despite these remarks, he was aware of the fact that he can never rule Italy without support from its oldest and most powerful institution. Within only a few weeks, the fascist leader would change his tune towards the Vatican. He initiated a process of accommodating them which lasted throughout the 1920s. He married in church and baptized his children, withdrew his “dirty” novel from circulation and in his first parliamentary speech in May 1921, he announced:

The only universal values that radiate from Rome are those of the Vatican.

The same transformation could be found in the Futurist movement, or at least with its founder. Marinetti was an opponent of the church for almost his entire career. In 1918, Marinetti wrote:

Our anticlericalism wishes to free Italy from churches, priests, frairs, and nuns, from madonnas, candles, and church bells. 55Ibid., 327.

Marinetti was frustrated in 1919 to see that Mussolini was turning to the Right and showing willingness to cooperate with the papacy and also monarchists. That created a rift between the Futurists and the fascists. In the same year, he wrote an article titled Against the papacy and the Catholic mentality, in which he declared:

It is a waste of time listing all the political reasons which make it absolutely essential for a victorious Italy to free herself from the Papacy, as soon as possible. […] I demand the expulsion of the Papacy so as to rid Italy of the Catholic mentality. 56Ibid., 323.

His hostility to the church continued for many years. In a lecture in Florence, he said:

Throughout its history, the Vatican has defecated on Italy. 57António Costa Pinto: Rethinking the Nature of Fascism: Comparative Perspectives (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 142.

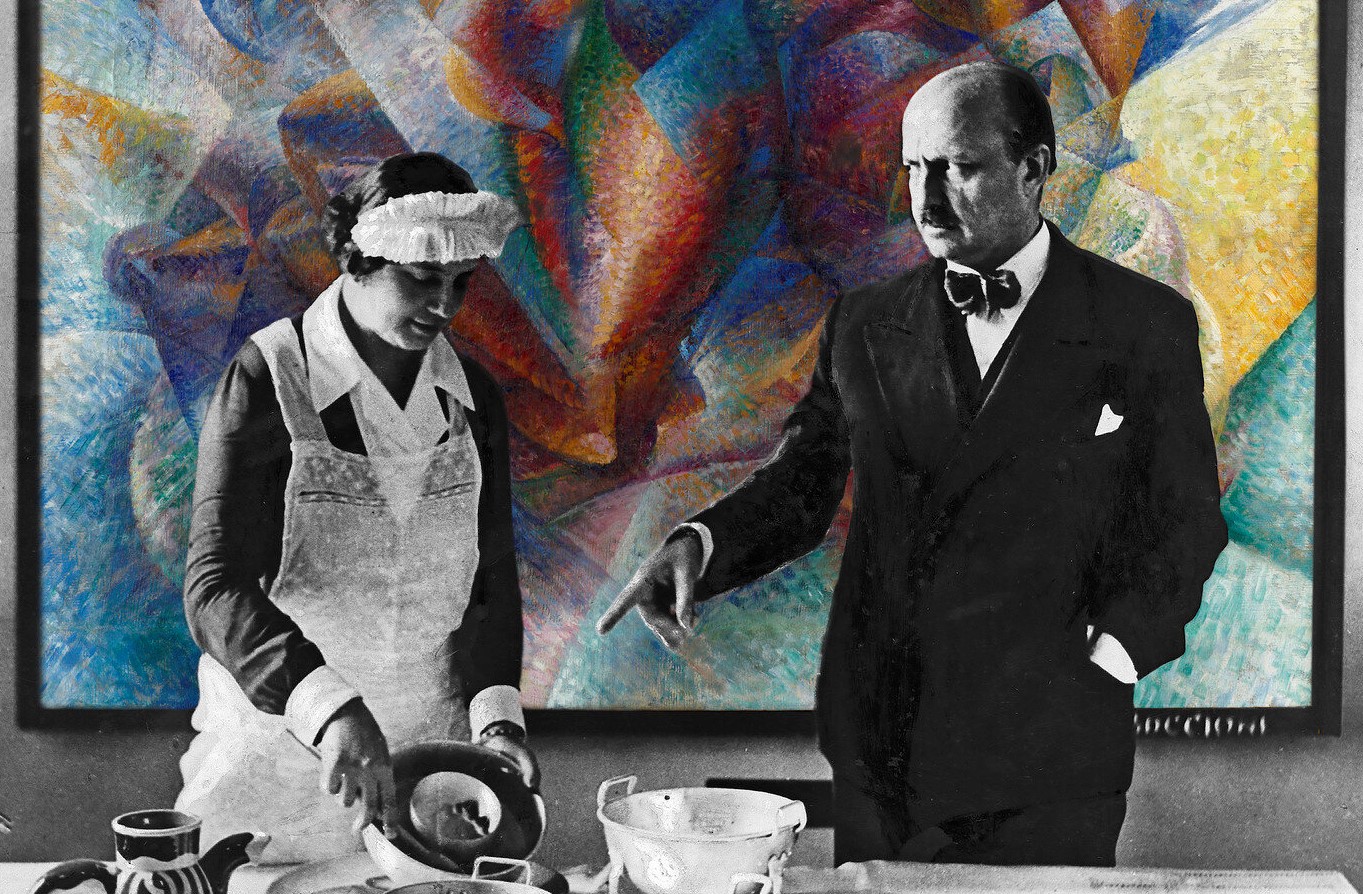

Around the same time, it was becoming clear that Mussolini was forming an alliance with the Papacy, culminating in 1929 with papal recognition of the Fascist government, while leaving the pope a sovereign state in the heart of Rome. Marinetti, in an incredible volte face, seemed to accept Catholicism. The aging man who spent quarter of a century railing against the Catholic church, decided to embrace it. He published in 1931, Manifesto of Futurist Sacred Art and participated in the Vatican’s International Exhibition of Sacred Art. He tried to explain to his puzzled supporters that one could salvage spiritual elements from traditional religion to help create Futurist art. He even declared that Jesus was a futurist!

Approaching death, in 1944, he wrote his last “aeropoem,” as he used to call his recent type of poems. It was titled L’aeropoema di Gesù (The Aeropoem of Jesus). In the booklet, after the religious meditations, there was an article in the appendix titled: 15 recommendations for the education of the ideal Catholic writer.

This is not to insinuate that the final “pseudo-religious” days of Marinetti had any official links with Fascist politics. He had become marginal. However, this demonstrates how his religious transformation reflected the official state alliance with the Vatican. During both his anti-Catholic and Catholic phases, one thing stayed the same:

The only religion is the Italy of tomorrow. 58F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 272.

16. Suppression through secret police (national security)

Marinetti, himself, was spied on by the police throughout his life. Hence, he had an anarchist view of the police. He called for minimizing the police force and the abolition of their secret department:

Reform and purging of the police. Abolition of the secret police. Interdiction of army intervention for the purpose of restoring public order. 59Ibid., 273.

He called for citizens and communities to enforce law and order themselves:

[W]e wish to abolish the existing system of policing and public order, reducing to a minimum the present complicated yet ineffectual protection of the citizen, who must—above all else—be responsible for protecting himself. 60Ibid., 281.

17. A yearning for a bygone golden age

There was a clear difference between the Futurists and fascists in regards to how they viewed the ancient Roman empire. The Futurists detested that era and considered living in the shadows of the great empire to be akin to “living in the past.”

Let us forget the ancient Romans so as to create the great Italians of the future. 61Ibid., 239.

Marinetti called for bulldozing the Roman ruins. He also called for the destruction of museums and selling monuments overseas in bulk. In short, the Futurist dream was a modern Italy greater than ancient Rome.

The tiresome memory of the greatness of Ancient Rome must be eradicated by an Italian greatness that is a hundred times more impressive. 62Ibid., 74.

The fascists, led by Mussolini, took a different route, perhaps under the intoxication of power. Italian fascists looked forward to ruling over an empire like their ancestors once did. For example, the so-called Roman salute was adopted by Italians in 1923, then adopted by Nazi Germany in 1926. The fascist vision of training children to be ideal citizens whose virtues include honor and discipline were partially inspired by Roman stories. To fascists, parades and military marches were all reminders of the by-gone grandeur. In 1936, Mussolini’s victory speech following the second Italo-Abyssinian War was translated into Latin and published in a fascist magazine. Mussolini, who saw himself as a modern-day Caesar, approved of it. That year, the fascists must have felt that the dream is becoming reality as they now rule lands as far as modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Whether the dream was an Italy greater than ancient Rome or just as great, whether they loved it or hated it, both the Futurists and the fascists were equally obsessed with comparing the rising young nation to the Roman empire.

18. Propaganda: Control of mass media

Marinetti never spoke of government controlling the media per se, but as an early pioneer of propaganda, he was most likely a supporter. Propaganda is the propagation of information, some of which might be misleading, to manipulate people’s feelings and actions. And that’s what the founder of Futurism aimed for. He is considered an early “master of the media” who knew how to spread the Futurist message in writings, art and publicity stunts! He was a provocateur and showman with concert tours. He held serata (evening meetings) to spread his message in cities around Italy. He worked with Italian government officials to spread war-time propaganda during World War I. Italian generals had heard about him on the news and they liked his “tough” nationalist messages, hence they invited him in 1917 to work with them.

Futurism [is] the militarization of innovative artists. Futurism marked very precisely the breakthrough of war into art when it created that most effective form of propaganda, the Futurist serata. 63Ibid., 239.

Italian Futurism, the ideological origin of fascism

As has been demonstrated above, futurism laid the philosophical foundation of fourteen of twenty characteristics of fascism. It should also be noted that two characteristics would emerge only as fascists took rule of governments:

19. Political corruption: Cronyism and fraudulent elections

20. Cult of the leader

One could conclude that almost all Futurist ideals were exported into fascism. The main exception is the obsessive glorification of technology and machines.

Why has it been debatable, despite the evidence, that Futurism inspired fascism?

Perhaps because the public was fascinated by the quirky and rebellious celebrity, that is F. T. Marinetti. Or perhaps because we feel uncomfortable with the fact that the words of a poet could inspire evil and bring about incalculable suffering. It could also be that he founded an art movement, and since when those who create beauty on canvasses are associated with violent dictatorships? Finally, it might be that his movement, the first cultural phenomenon to celebrate youth, speed and technology, is just too similar to our pop culture, which makes writers reluctant to tarnish it with fascist associations!

How Futurism ended?

Historians disagree on when Futurism ended. Some consider 1914 the final year since internal disagreements disintegrated the original group. Some consider Italy’s late involvement in WWI, in 1915, the end of Futurism. Many of the Futurists happily enlisted and some of the key members perished in the fight. It could be that 1920 was the end when Marinetti quit politics. He took that decision after the previous years’s disastrous results of the national elections which led him to the decision of letting the Futurist Party be absorbed into the new Fascist Party. Note that many Futurists quit the party following that alliance with Mussolini’s party. Some writers treat 1923 as the year Futurism died as Marinetti accepted that the Fascist government would not allow Futurism to be the official art of the state, i.e. politics and art would have to live on in separate spheres.

One might consider Marinetti’s return to the Catholic Church in 1931, after a lifetime of being anti-conservative and anti-clerical, the end of Futurism. Marinetti’s death in 1944, one year before the end of WWII and the collapse of Italian fascism, was ultimately the closing of that chapter. He was not just the founder of Futurism, but he nurtured a personality cult equating him with the entire movement. Perhaps, it is a futile exercise pinpointing the movement’s end: Futurism did not die young with its “jackboots” on. It aged and slowly perished over the decades while its utopian dreams evaporated.

You might also like:

Mussolini and Marinetti: A Timeline of the Fascist-Futurist alliance

The uneasy coalition between a poet and a dictator ended up in destroyed dreams

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

The misogynist who supported feminist causes—mostly inadvertently

The Italian Futurist poet, F. T. Marinetti, was a misogynist and a proto-feminist all at once

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

‘Destroy museums!’–Why an Italian waged war against the past

Those who embraced state-sponsored iconoclasm as a fast track to modernization

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Three possible reasons why Italy lagged behind Europe for centuries

Why Italy’s modernization has been, and continues to be, problematic?

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Endnotes