Voltaire’s Candide, or Optimism (1759), is a story of a young man who believed in his tutor’s rosy worldview that “all is for the best.” Throughout the book, he’s on a pursuit to find the girl he loves, while facing off a litany of challenges which bring him against the worst humanity could offer. Read below the thought-provoking passages from one of the most controversial novels ever written.

The German region of Westphalia is where Candide lives. He’s the illegitimate son of the baron’s sister. The castle’s mentor, and Candide’s personal tutor, is Pangloss who believes that the world is “the best of all possible worlds.” One day the gorgeous daughter of the baron, Cunégonde, flirts with Candide (cousin relationships were not taboo) and they share a kiss behind a screen. Her father catches them, and in a fury he kicks Candide out of the castle. This marks the start of a series of tragic events which will test his faith in his tutor’s ideas.

As he’s wandering out of town cold and penniless, two men find him and act kindly at first, then force him into military service for the King of the Bulgars. He gets mistreated and abused everyday. One day, he goes on a walk, without permission or understanding of the rules, he gets caught and sent to execution as a deserter of the army. The King, passing by, stops the execution at the last moment after explaining that Candide’s actions and words betrays the naïveté of some kind of philosopher!

He recovers from the pre-execution torture and joins a war of Bulgars versus Abares. On both sides, villages were burnt and civilians were killed. Candide then escapes to Hollande where his first experience will be literally shitty.

He sees a Protestant orator (pastor) preaching publicly to a crowd about charity. Hungry Candide expects to receive some “brotherly love” with a bit of food from him but instead he gets questioned on his religious allegiance. (By the time of publishing this book Protestants and Catholics had long been enemies.)

‘But my friend,’ said the orator, ‘do you believe that the Pope is AntiChrist?’

‘I’ve not heard it said before now,’ replied Candide, ‘but whether he is or is not, I am in need of food.’

‘You don’t deserve to eat,’ said the [orator]. ‘Be off, you wretch! Out of my sight, you miserable creature! And don’t ever approach my person again.’

The orator’s wife, putting her head out of the window and catching sight of somebody who could doubt that the Pope was Anti-Christ, discharged over his head a chamber pot full of … Heavens! To what extremes is religious zeal sometimes carried by the ladies!1Voltaire, Candide, or Optimism, trans. Theo Cuffe (London, United Kingdom: Penguin Classics, 2005), 9.

Without questioning Candide’s beliefs, an Anabaptist (of the same doctrine as the Amish) takes him into his home, feeds him, gives him a job in his rug factory.

The following day, he sees a beggar covered with sores, then realizes that it’s his tutor, Pangloss. He learns from Pangloss that the Baron, Baroness, Cunégonde and her brother were all killed by soldiers and that he contracted syphilis which he traces back, as was commonly misbelieved, to the Caribbean islands. Then Voltaire, through Pangloss, mocks the supposed celibacy of members of strict Catholic orders who engage in all kinds of sexual promiscuity of homosexual and even pedophilic nature:

Pangloss replied thus: ‘My dear Candide! You remember Paquette, the pretty lady’s maid to our august Baroness; well, in her arms I tasted the delights of paradise, which in turn provoked the torments of hell by which you see me devoured; she was herself infected, and may now be dead. Paquette received this present from a very learned Franciscan, who could trace it back to its source: for he had been given it by an old countess, who in turn had it from a cavalry captain, who was indebted for it to a marquise, who caught it from a page-boy, who contracted it from a Jesuit; who, while a novice, had inherited it in a direct line from one of the shipmates of Christopher Columbus. As for me, I will pass it on to no one, for I am dying of it.’

‘Oh Pangloss!’ cried Candide, ‘what a strange genealogy is this! Surely the devil is its source?’

‘Not in the least,’ replied that great man. ‘It is an indispensable feature of the best of all possible worlds, a necessary ingredient: for if Columbus, on an island off the Americas, had not contracted this disease…we would have neither chocolate nor cochineal [an insect from Mexico used to create a red dye]’.2Ibid., 11.

The unceasingly optimistic Pangloss claims that the legendary explorations introduced a venereal disease but let’s not forget they also brought us chocolate!

The Anabaptist pays for the medical treatment of Pangloss who recovers although he loses an eye and an ear. Several weeks later the Anabaptist, Candide and Pangloss travel for business by boat to Lisbon. A storm overtakes and destroys their ship. The Anabaptist, one of the most humane characters in the story, drowns in the storm, while rescuing the sailor who survives with Pangloss and Candide. Everyone else on the ship drowns.

They float on planks which take them to the shore. They’re received in Lisbon with a major earthquake that kills tens of thousands of people. (This is a reference to an actual 1755 Lisbon earthquake which was so violent that around 30,000 people perished.) The sailor gets drunk, steals money from the quake victims, and pays a whore for sex to a soundtrack of groans from people injured or still buried in the ruins. Pangloss can’t help but philosophize even in the face of corrupt characters like the sailor. He reprimands the sailor and tells him that his conduct breaks “the laws of universal reason.” The sailor retorts:

‘Hell and damnation! …I am a sailor born in Batavia; I’ve made four voyages to Japan, and four times I’ve trampled on the Cross; you’ve picked the wrong man, with your drivel about “universal reason.”‘3Ibid., 14.

It was reported that Europeans had to repudiate their religion by trampling on a crucifix before they could engage in trade with the Japanese who perceived Christian missions as another arm of European imperialism. 4Ibid., 128.

Candide and Pangloss helped the quake victims while consoling them with their positive “all for the best” spiel and that somehow the disaster was a necessity. An officer of the Inquisition overhears Pangloss and traps him with two questions: How is this “the best of all possible worlds” if our very existence is a punishment for the original sin (Adam and Eve’s disobedience and subsequent banishment from the Garden of Eden)? Why would that “original sin” happen in the first place, putting us all in a state of guilt, if all is for the best?

From the perspective of the Inquisition officer, Pangloss is essentially advocating a false doctrine. You can guess what’ll happen next…

After the earthquake, which had destroyed three-quarters of Lisbon, the sages of that country could think of no more effective means of averting further destruction than to give the people a fine auto-de-fé [execution by burning]; it having been decided by the University of Coïmbra [universities are not always centers of enlightenment!] that the spectacle of a few individuals being ceremonially roasted over a slow fire was the infallible secret recipe for preventing the earth from quaking.

Consequently they had rounded up a Biscayan [from the Spanish Basque] who stood convicted of marrying his fellow godparent [i.e. he married his godmother], and two Portuguese who were seen throwing away the bacon garnish while eating a chicken [most likely Jews]. After dinner some men arrived with ropes and tied up Doctor Pangloss and his disciple Candide – the one for what he had said, and the other for having listened with an air of approval.5Ibid., 15.

Pangloss was not burned at the stake, he was sentenced to just a public hanging, as for Candide, his punishment was a public flogging. Despite all the executions in the name of God and the “magnificent auto-de-fé,” divine mercy never came and another earthquake happened later that day.

An old woman who works as a servant took Candide to treat his wounds after the flogging and to feed him. Later, the old woman leads him to the person who sent for his help: Cunégonde herself. Cunégonde explains to him that she, unlike her family, actually survived the Bulgar soldier attack. Later, when a Bulgar captain caught a soldier raping her, he killed him. The captain kept her as a sex slave for three months before he sold her to a Jewish businessman named Don Issachar. Then while Cunégonde was in church on a Sunday morning…

‘The Grand Inquisitor [the same one who ordered the executions] noticed me one day at Mass; he ogled me throughout the service, and then sent word that he had to speak to me on private business. I was taken to his palace; I informed him of my birth; he pointed out how far beneath my rank it was to be the chattel of an Israelite. A proposition was made on his behalf to Don Issacar, that he should hand me over to His Eminence the Inquisitor. Don Issacar, who is the court banker and a man of parts, preferred to do no such thing.’

‘The Inquisitor threatened him with an auto-da-fé. At last my Jew, intimidated, agreed to a compromise, whereby the house and my person would belong to both of them in common; the Jew would have Mondays, Wednesdays and the Sabbath, the Inquisitor would have the other days of the week. This arrangement has lasted for six months. It has not been without its quarrels, namely as to whether the night between Saturday and Sunday belongs to the old law [Jewish Saturday] or to the new [Christian Sunday]. For my part, I have so far resisted them both, which I am sure is the reason they both love me still.’

‘Finally, to avert the scourge of further earthquakes, and to intimidate Don Issacar, His Eminence the Inquisitor was pleased to hold an auto-da-fé. He did me the honour of inviting me. I had an excellent seat; refreshments were served to the ladies between the Mass and the executions.'6Ibid., 20.

And that’s where, to her horror, she spotted Candide.

While Cunegonde was telling him her story, Don Issachar walks into the house to find them alone. In a fit of protective rage, Candide kills him with a sword that the old woman swiftly handed him. Before Candide could even recover from his deed, the Inquisitor walks in. Candide kills him too. The three of them, Candide, his girl and the old woman, take their belongings and escape on horseback. The old woman was initially hesitant to ride because she said she has only one buttock. (More on this later.) In death, as in life, the Inquisitor received a different treatment from that of the Jew:

His Eminence the Inquisitor was buried in a beautiful church, and Don Issacar was thrown on to the town refuse heap [a dunghill].7Ibid., 23.

On their journey, they spent the night at an inn, where Cunegonde’s jewels and money were stolen. In an ironic twist, it seems like the thief belongs to a group whose members vow to live in poverty for life:

‘Alas!’ said the old woman, ‘I strongly suspect it was that reverend Franciscan who slept in the same inn as us last night in Badajoz; God preserve me from making rash Judgements, but he passed through our room twice and he set off long before us.'8Ibid.

They sell one of the horses to raise more money and decide to travel towards Cadiz, in Spain, where there’s ships heading towards the New World (Buenos Aires is their destination). Perhaps that New World of the Americas (that is, Latin America) will prove to be truly the best of all possible worlds, which many, back then, actually believed. Cunégonde is no longer certain that things could be better, but the old woman admonishes her and tells her basically “you’ve had it easy compared to me!” Then she started telling her story:

‘I did not always have red-rimmed and bloodshot eyes; my nose did not always touch my chin, nor was I always a servant. I am the daughter of Pope Urban X and the Princess of Palestrina.'9Ibid., 25.

(Although this pope is fictitious, that line is a reference to the notorious religious hypocrisy of some supposedly celibate popes who were either sexually active or even promiscious. At least six of them fathered children during the 15th and 16th centuries.)

In her younger years, when she used to be gorgeous, she got engaged to a very handsome prince but his jealous mistress poisoned him. She and her mother set sail to a vacation estate for a mourning period in Gaeta, north of Naples under the protection of the Pope’s soldiers. (Yes, the Pope had an army that waged wars and forged treaties for hundreds of years.)

‘The next moment a pirate ship from Salé [a Moroccan port long associated with Moorish pirates] swept down and boarded us. Our men defended themselves as the Pope’s soldiers usually do: they all fell to their knees, threw down their weapons, and begged the pirates to absolve them of their sins in articulo mortis‘.10Ibid., 26.

One of the most brilliant and absurd moments in the book: Not only did the Pope’s soldiers act cowardly, they also knelt before non-Christian criminals begging for their in articulo mortis forgiveness (literally, at the moment of death) which is a “sacrament” and a final act of penance that requires a Catholic priest.

‘They were promptly stripped naked as monkeys, as were my mother, and our maids of honour, and I myself… they then took each of us and inserted their fingers into that orifice which we ladies usually reserve for an enema syringe [popular and useless treatment to a range of illnesses from stomach ache to flu symptoms]…I soon learned that its purpose was to discover if we had hidden any diamonds there.'11Ibid.

The strip search was followed with rape:

(Note that the horrific crimes below have undertones that reveal common stereotypical views of foreigners. One could even describe them as racist however Voltaire’s views on race were complex as explained below in a scene with an African slave.)

‘As for me, I was ravishing, I was beauty itself, grace incarnate – and a virgin to boot. Not for long, of course; this flower which had been reserved for the handsome Prince of Massa-Carrara, was plucked by the Corsair captain, an abominable negro, who of course believed he was doing me a great favour.'12Ibid.

The pirates took the captives to sell them as slaves in Morroco, which was engulfed in a civil war, as they found out upon disembarkment. Countless “horny African” men fought the pirates over the women:

‘Next to the diamonds and gold, we were the most precious part of his cargo. I was witness to a combat the like of which would never be seen in your European climes. Northerners do not have sufficiently hot blood. They do not have that raging lust for women so common in Africa.

…

At length, I saw all our Italian maids and my mother cut to pieces, torn apart, massacred by the monsters who contended over them. My fellow captives, and their captors – soldiers, sailors, blacks, browns, whites, mulattos and finally my captain – all were dead; and I remained alone, dying under a heap of dead bodies. Similar scenes were taking place, as everyone knows, over an area of more than three hundred leagues, without anyone ever omitting to say their five daily prayers as required by Mahomet.'13Ibid., 27.

(Voltaire here makes the same point he made above that there is no connection between following religious practice and being a good person. He’s using satire to show that often Muslims, like Christians, are guilty of religious hypocrisy.)

Eventually, after the battle was over, she came back to consciousness:

‘I was in this state of feebleness and insensibility, hovering between life and death, when I felt the pressure of something rubbing up and down on my body. I opened my eyes; I beheld a white man, rather attractive, who was moaning on top of me and muttering through clenched teeth: O che sciagura d’essere senza coglioni! [Oh, what a shame to be without testicles!]'14Ibid., 28.

(The man attempting to rape her is one of the Italian castrati, the unfortunate choirboys dedicated to the Catholic Church at a young age and castrated before puberty in order to preserve their high pitch voice.)

Despite the attempted rape, the woman is delighted to meet a fellow countryman! He carries her to his cottage to look after her. He promises to take her back to Italy, but instead he travels to Algiers (Algeria) where he sells her to the governor as a concubine.

The bubonic plague sweeps though the region killing the governor and the eunuch. But doesn’t bring her freedom because she’s captured and sold several times. She ends up in the harem of a Muslim military commander who travels everywhere with his concubines. The commander, being from Algiers which was part of the expansive Ottoman Empire, had to follow orders and travel to fight with the Turks (the Ottomans are Turks) against Russians attacking the city of Azov. (Today Azov is part of Russia which is a clue to the outcome of the historically accurate battles and horrific siege which lasted from 1695 to 1697.)

At one point in the woman’s story, she says the Russians destroyed the whole city and only their fort was left standing. While under siege and in the grip of starvation, they killed two eunuchs and ate them. (Eunuchs were not unique to Christian Europe: They had a constant presence in Ottoman harems.) Then as they were about to kill the women, an imam (a Muslim cleric) intervened:

‘We had a very pious and compassionate imam, who delivered an excellent sermon persuading them not to kill us outright. “Cut off one buttock,” he said, “from each of these ladies, and you will be well provided for; if you have to come back for more in a few days’ time, you can take as much again; heaven will smile on so charitable an action, and you will be rescued.”‘

‘He was all eloquence; they were convinced; and we were subjected to this dreadful operation. The imam applied to our wounds the ointment they use on boys who have just been circumcised. We were all at death’s door.'15Ibid., 30.

After their lives were spared and they were “mercifully” mutilated, the Russians attacked and killed all the soldiers. She, along with the other women, were taken to Moscow where she became a slave. Later, she managed to escape. At that point in her storytelling the ship approaches Buenos Aires. After the ship is docked, they visit the governor who was taken by the beauty of Cunégonde. He asks Candide if they were married.

The manner with which he asked the question disturbed Candide, who dared not say yes, for she was not in fact his wife, and who neither dared to call her his sister, for she was not that either; and although this white lie was once very fashionable among the Ancients, and could still have its uses for the Moderns, his heart was too pure to betray the truth.16Ibid., 32.

(“The Ancients” is a cunning remark aimed at mocking biblical morality where both Abraham and Isaac in different stories lied about their wives and claimed they’re their sisters – Genesis 12:13 and Genesis 26:7.)

Candide naïvely tells the truth that he intends to marry her one day. So the governor then sends him away on a mission, then offers to marry Cunégonde. The old woman advises her to do so to acquire wealth – not easy to resist such advice when you’re completely broke.

In the meantime, the Franciscan friar tried to sell the jewels stolen from the main characters but officials recognize they belong to the murdered Grand Inquisitor. He gets executed but not before he makes a confession on whom he stole the jewels from. Now Portuguese officials are in town seeking to arrest the murderers of the Inquisitor. The old woman assures Cunégonde not to worry since the governor will protect her, but Candide should flee immediately.

Candide and his servant, Cacambo, escape to a nearby Jesuit camp. Candide finds out that the colonel of the camp is the brother of Cunégonde, who actually survived the attack. Her brother is surprised to know from Candide that she, too, survived. Then he started telling of the misfortunes he experienced to Candide and how he ended up as a Jesuit in the Americas. He hints of a homosexual attraction as the reason behind a priest taking him into the religious order.

You will recall, my dear Candide, how pretty I was; well I became even more so, to the point that the Reverend Father Croust, who was Superior of the community, conceived the most tender affection for me; he initiated me as a novice.17Ibid., 37.

(Again, Voltaire is condemning the hypocricy of priests and monks who vow celibacy yet engage in scandalous affairs within the walls of their churches and monasteries.)

Now that the father is dead, Cunégonde’s brother is the new baron, so Candide made a request:

‘That is all I could wish for…I was intending to marry [Cunégonde], and hope to do so still.’

‘What an extraordinary piece of insolence!’ retorted the Baron. ‘So you would have the effrontery to marry my sister, who has seventy-two quarterings on her coat of arms! I consider it highly presumptuous of you to dare to speak to me of so rash an intention!’

Candide, whose blood turned cold at this outburst, replied: ‘Reverend Father, all the quarterings in the world make no difference; I have rescued your sister from the arms of a Jew and an Inquisitor; she has certain obligations towards me, and she wishes to marry me. Maitre Pangloss always told me that all men are equal; you may depend on it that I shall marry her.’

‘We shall see about that, you dog!’ said the Jesuit Baron of Thunder-ten-tronckh, and with these words struck him a great blow across the face with the flat of his sword. Candide instantly drew his own sword and plunged it up to the hilt in the Jesuit Baron’s belly; as he withdrew it, all steaming, he began to weep.18Ibid., 38.

(Poverty is one of three vows the Jesuits take. The others are obedience and chastity. As clear from the story, many of them have trouble keeping the at least two of the three. As obvious from the above passage, even though the brother was a Jesuit priest, a world away from Europe’s class structure, he still views Candide, who rescued his sister from sexual servitude, as too inferior to marry her. Money, status and aristocratic superiority were still of higher value than his own Jesuit vows or Candide’s gracious character.)

Sixteen Quarterings (Seize Quartiers) refers to a coat of arms with sixteen partitions demonstrating four generations of pure noble ancestry, meaning not a single commoner between themselves and their 16 great-great-grandparents. It was considered the ultimate and hardest-to-obtain proof of pure blood. (View a visual example of a genealogy with sixteen quarterings.) Therefore, Cunégonde’s seventy-two quarterings is a ridiculously high number, and a joke at the expense of aristocratic families. It gets more absurd: Candide’s supposed inferiority, as perceived by Cunégonde’s family, is due to his lack of proof for more than seventy-one quarterings!

Cacambo walks in on the murder scene. He dresses Candide in the Colonel’s habit and they flee. Then they end up in a strange territory where they encounter “ass-biting monkeys”:

The shrieks were coming from two quite naked girls, who were tripping lightly along the edge of the meadow, pursued by a pair of apes snapping at their bottoms.

…

So [Candide] now raises his double-barrelled Spanish rifle, fires and kills both apes.

‘God be praised, my dear Cacambo! I have delivered these two poor creatures from grave peril.’

…

‘Master; you have just despatched [killed] the two lovers of these young ladies….

Why do you find it so strange that in some countries it is apes who enjoy the favours of young ladies? After all, they are one-quarter human.'19Ibid., 39.

(This is a bizarre story that makes you wonder what purpose it might serve. Beyond being enigmatic it also poses a problem regarding who the monkeys represent. Do they stand for an “inferior” racial group at a time when theories of ethnic hierarchy were commonly accepted? Or should we take the story at face value that they are just that, monkeys, meaning they’re in the same category with humans? There is evidence that the latter might be more plausible considering that long before Darwin’s theory of Evolution (1859), scientists controversially pointed to similarities between humans and apes. That comparison was made by British scientist Edward Tyson, 1651–1708, and in the 1735 book Systema Naturae by Carl Linnaeus, 1707–1778.)

They find a place to hide and fall asleep. But the tribe to which the two girls belong finds them:

When they awoke they found they were unable to move their limbs; the explanation for which was that the Oreillon tribe…had tied them down during the night with ropes made of bark. They were now surrounded by fifty or so stark-naked Oreillons, armed with arrows, clubs and flint axes: some were bringing a large cauldron to the boil; others were preparing spits, and all of them were chanting: ‘It’s a Jesuit! It’s a Jesuit! We will be avenged! And we’ll eat our fill! Let’s eat Jesuit! Let’s eat Jesuit!’

…

‘Don’t despair,’ [Cacambo, who’s of mixed ethnicity] said to the dejected Candide. ‘I am familiar with the gibberish these people speak. I will address them.’

‘Be sure to impress upon them,’ said Candide, ‘how frightful and inhuman it is to cook people alive, and how very unchristian.'20Ibid., 40.

In their own native language, Cacambo is able to convince them of the mistaken identity and that Candide is not a Jesuit but a killer of one. They’re shown hopitality after.

(Note how our naïve hero would like the tribe to know that it’s unchristian to be cannibals yet most likely they’re not Christians! Voltaire intended with this story to attack the common view of the “noble savage” regarding the natives and to show the’re capable of violence – and worse, like cannibalism – just like other Europeans in the story. Soon after the publication of Candide, “Let’s eat Jesuit!” – Mangeons du Jésuite! – became proverbial with the French public whose hostility to the group increased to the point of expulsion in 1764.)

They continue on their journey and they come across a utopian village, Eldorado, where the streets are paved with gold. They meet the oldest man in the village:

‘My friends’ he said, ‘we are all of us priests. The King and the heads of each family sing solemn hynms of thanksgiving every morning, to the accompaniment of five or six thousand musicians.’

‘What! You have no monks instructing and disputing, and governing and intriguing, and having everyone burned alive who is not of their opinion?’

‘We would have to be foolish indeed,’ said the old man. ‘Everyone here is of the same mind and we cannot imagine what you mean by this talk of monks.'21Ibid., 47.

(Here Voltaire criticizes his own society by presenting the perfect world in his view: relative equality, appreciation for science, no greed, nor religious persecution or bigotry, and every night they worship God in unison and harmony. Perhaps Voltaire knows that this place could never exist because it’s one where all people agree on and believe in the same things.)

Candide and Cacambo loaded 102 sheep with “pebbles” of gold collected off the side of the road in Eldorado then our hero (or, rather, anti-hero) started to dream of having his own kingdom. Next destination on their journey was Surinam, a Dutch Colony…

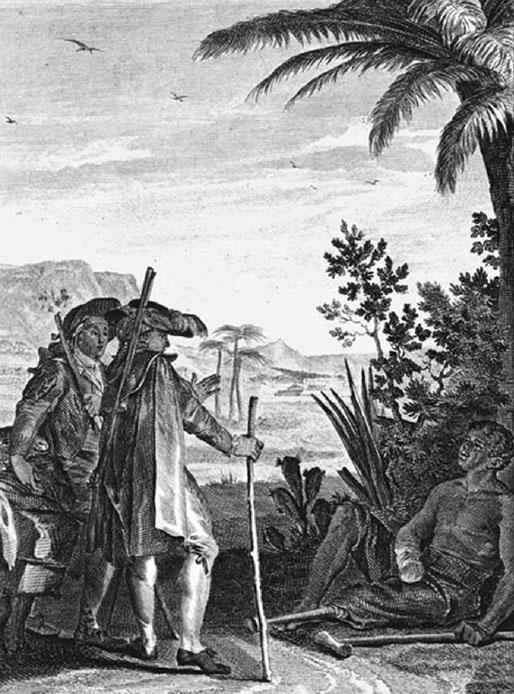

As they drew near to the city, they came across a negro stretched out on the ground, with no more than half of his clothes left, which is to say a pair of blue canvas drawers; the poor man had no left leg and no right hand.

‘Good God!’ said Candide to him in Dutch. ‘What are you doing there, my friend, in such a deplorable state?’

‘I am waiting for my master, Monsieur Vanderdendur, the well-known merchant,’ answered the negro.

‘And was it Monsieur Vanderdendur,’said Candide, ‘who treated you like this?’

‘Yes, Monsieur,’ said the negro, ‘it is the custom. Twice a year we are given a pair of blue canvas drawers, and this is our only clothing. When we work in the sugar-mills and get a finger caught in the machinery, they cut off the hand; but if we try to run away, they cut off a leg: I have found myself in both situations. It is the price we pay for the sugar you eat in Europe. Yet when my mother sold me for ten Patagonian écus [Spanish American coins] on the coast of Guinea, she told me: “My child, give thanks to our fetishes [sacred objects worshiped in tribal societies], and worship them always, for they will make your life happy; you have the honour to be a slave to our white masters, and therefore you are making the fortune of your father and mother.” Alas! I don’t know if I made their fortune, but they certainly didn’t make mine. Dogs, monkeys and parrots are a thousand times less miserable than we are; the Dutch fetishes [a reference to Protestant missionaries] who converted me to their religion tell me every Sunday that we are all children of Adam, whites and blacks alike. I am no genealogist; but if these preachers are telling the truth, then we are all second cousins. In which case you must admit that no one could treat his relatives more horribly than this.’

‘Oh Pangloss! [addressing his absent mentor]’ cried Candide. ‘This is one abomination you could not have anticipated, and I fear it has finally done for me: I am giving up on your Optimism after all.’

‘What is Optimism?” asked Cacambo

‘Alas!’ said Candide, ‘it is the mania for insisting that all is well when all is by no means well.’ And he wept as he looked down at his negro, and was still weeping as he entered Surinam.22Ibid., 51.

This somber encounter with a mutilated slave could be considered the most powerful and important scene of the book. The conditions of slavery were so cruel that Voltaire thought it inappropriate to use his typical dark humour found in other scenes where, for example, Candide gets human excrement dumped on his head or the old woman has one of her buttocks cut off and eaten.

(Up to that point, Candide, being overwhelmed with misfortunes, had been oscillating between two views : “all for the best,” as taught by Dr. Pangloss and “this is a cruel, unjust world.” However, only at this epiphanic moment standing before a slave, he announces his rejection of optimism, at least for now.)

This somber encounter with a mutilated slave could be considered the most powerful and important scene of the book. Read an analysis of the scene.

Candide sends Cacambo alone to retrieve Cunégonde and the old woman and bring them to Venice where they’ll all meet. He finds a man to take him to Venice who happens to be the owner of the slave. He turns out to be a swindler who promises a trip on his ship to Candide but after the latter puts his sheep on his ship, loaded with riches, he sails away. Back in the city, he tries to pursue a legal solution by complaining to a judge but he is not taken seriously. He eventually finds another ship sailing to France which he boards along with a miserable, hopeless companion named Martin.

As the French coast came into view Candide asks Martin about his travels:

‘But have you been to Paris, Monsier Martin?’

‘Yes, I’ve been to Paris… I stayed there only briefly; on my arrival I was robbed of all I had by pickpockets at the Saint-Germain fair; I was then taken for a thief myself, and spent eight days in prison…I came to know all sorts of rabble – the hacks and scribblers, the political intriguers, and the holy rabble who trade in religious convulsions. I am told there are some civilized people in that city; I should like to think so.'23Ibid., 58.

After their ship arrives in France, the two men decide to visit Paris where they meet an abbé, a clergyman who might or might not be consecrated. (Through his character, Voltaire will provide yet another example for the immorality of Church clergy.) The abbé introduces the visitors to a woman who insists on being called the Marchioness of Parolignac. She seduces Candide into her dressing room and they have sex, after which he feels remorseful because in his heart, he feels he belongs only to Cunégonde. Then the abbé tricks him out of his gold and diamonds. By the time he and Martin realize they have been duped, an officer arrives, at the request of the abbé, to arrest them for being “suspicious strangers.” They bribe the officer and flee on a ship to England.

Then they had another travel-related conversation:

‘You have been to England,’ said Candide. Are they, as mad there as in France?’

‘It’s a different type of madness, said Martin. As you know, the two countries are at war over a few acres of snow on the Canadian border, and they are spending rather more on their lovely war than the whole of Canada is worth.'24Ibid., 69.

Voltaire famously called Canada a few acres of snow (quelques arpents de neige) but was he unique in seeing the Great White North as anything but “great”? No. Actually, that phrase would have resounded with the French public for two reasons. Read more on the historical context.

While the ship was docked at a port in England, he witnesses an execution. He asked…

‘And why kill this admiral?’

‘Because,’ came the reply, ‘he did not get enough people killed when he had the chance: he gave battle to a French admiral, and was said not to have engaged closely enough with the enemy.’

‘In which case,’ said Candide, ‘surely the French admiral was just as far from the English admiral as the English admiral was from the French admiral?’

‘Unquestionably so,’ came the reply, ‘but in this country it is considered useful now and again to shoot an admiral, to encourage the others.'25Ibid.

The execution of Admiral John Byng, on which this scene is based, is the outcome of one of the most notorious legal episodes in British history. Read the story here.

Out of disgust with this injustice, he decides not to set foot in England and requested that the Captain continue sailing to Venice where he’s certain he’ll reunite with Cunégonde.

After a few months in Venice, he still couldn’t find his beloved and became depressed. One day he meets a seemingly happy couple, one of whom is a monk (another promiscuous friar). The woman turned out to be the former mistress of Pangloss who infected him with Syphilis. After a series of misfortunes, she had to resort to prostitution to support herself. It turns out that the monk is only one of her clients and she’s actually far from happy:

‘But you looked so gay, so happy, when I ran into you just now,’ said Candide to Paquette; ‘you were singing, you were caressing your monk so naturally and affectionately; you seemed to be as happy as you now claim to be miserable.’

‘Ah! Monsieur,’ replied Paquette, ‘that is another of the miseries of our profession. Yesterday I was beaten and robbed by an officer of the law; today I must seem in good humour to please a monk.'26Ibid., 73.

Then after finding out how tragic the woman’s life has been, he turns to the monk to ask him if he’s happy:

‘I wish every last Theatine [a Catholic order to which he belongs] at the bottom of the sea. I have been tempted a hundred times to set fire to the monastery and go and turn Turk [convert to Islam]. My parents forced me at the age of fifteen to wear this loathsome habit, so as to leave a larger fortune to my accursed elder brother, whom God confound! The monastery is rife with jealousies, faction and ill-feeling. It is true, I have preached a few wretched sermons which brought me a little money, half of which the prior has stolen from me: the rest I use to pay for the girls; but when I get back to the monastery in the evening I feel like dashing my brains against the dormitory walls; all my fellow friars are in the same situation.'27Ibid.

Candide then meets a wealthy count in Venice who has an great collection of art and books but he finds no pleasure in them. The count makes a comment about freedom of speech which is perfectly aligned with Voltaire’s views:

‘[I]t is a fine thing to write what one thinks; it is man’s natural privilege, after all. In Italy, wherever you go, we write only what we do not think; the descendants of the Caesars and the Antonines dare not entertain an idea without the permission of a Dominican monk. However, I would be happier with the freedom which inspires the English genius, except that doctrinaire passion and party spirit corrupt all that is estimable in their precious liberty.'28Ibid., 77.

To modern readers, Voltaire’s reference to “the permission of a Dominican monk” might not be obvious but for centuries it was a clear allusion to the Inquisition. The Dominican monks played a prominent role in that dark chapter of Christian history where heretics were put on trial and subjected to torture, and countless of them were executed. The Inquisition started in the 12th century and lasted in some regions until the 19th century. Although the Spanish version was especially brutal, the Inquisition, as mentioned in the above quote, was established far beyond. Italy, in particular, had a long history of heresy trials before the Galileo affair (1633) thanks to the Papal Inquisition which lasted from 1231 to 1820. The shameful work undertaken by the Dominicans earned them a popular pun on their name in Latin: Domini Canes (God’s dogs). A graphic representation of that pun (i.e. dogs biting wolves, that is heretics) exists today in the Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence.

Candide’s hope in finding Cunégonde is rekindled when Cacambo shows up to tell him that he has become a slave and his beloved is in Constantinople working along with the old woman as servants for a prince. Candide buys Cacambo’s freedom then heads with him and Martin to Turkey to meet his girl. Upon his arrival in Turkey, Candide recognizes two galley slaves: They’re Cunégonde’s brother, who survived Candide’s stabbing and has no hard feelings towards him and Pangloss who survived the execution. Candide buys their freedom.

Next Candide buys back Cunégonde and the old woman. Then he acts on his promise and marries her even though she’s now ugly. Her brother was an obstacle to the marriage again so Candide, instead of killing him, returns him to the galleys. Candide is finally settled on a small farm with his wife and other friends. Now that they all found each other, and are living out of harm’s way, did they find happiness?

It would be altogether natural to suppose that Candide, after so many disasters, would henceforth lead the most agreeable of possible existences – married at last to his mistress, living with the philosopher Pangloss, the Philosophical Martin, the prudent Cacambo, the old woman – having moreover brought back all those diamonds from the land of the ancient Incas. But he had been swindled so many times by Jews [a passing anti-Semite remark about the “swindling Jews”] that all he had left in the end was his little farm; his wife, growing uglier by the day, had become shrewish and insufferable. 29Ibid., 90.

Not only does Candide feel unfulfilled, another unexpected problem appeared…

[T]he boredom was so extreme that one day the old woman ventured to remark: I should like to know which is worse: to be raped a hundred times by negro pirates…or simply to sit here and do nothing?30Ibid.

Paradoxically, peace, safety and the sudden lack of suffering might have been a reason why they were bored. Their hard work on the garden though provided them with a solution to counter that boredom and that’s how they ultimately find happiness. Candide is no longer infatuated with the theories of Pangloss which he makes clear in an iconic scene at the end of the book. Pangloss starts philosophizing to him as he always had done, then Candide, who now clearly prefers actual work, interrupts: That is well said…but we must cultivate our garden.

Note: All the above controversial passages are available in the original (French) language on this page.

You might also like:

Why Voltaire mocked Canada as ‘a few acres of snow’?

He also called it the land of ‘barbarians, bears and beavers’

BOOK: CANDIDE

Voltaire’s radical views on race and slavery

Understanding Voltaire’s view on race and slavery through the eyes of Candide

BOOK: CANDIDE

Endnotes