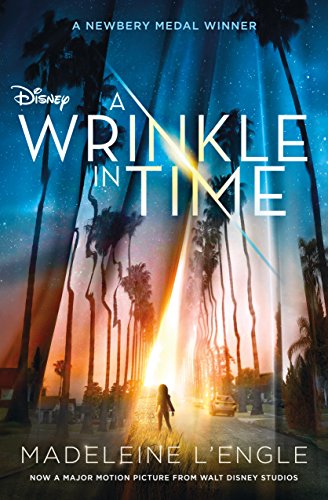

Summary of the novel featuring its controversial paragraphs

Meg’s father had been missing for two years. He was a scientist who worked on a secret project. Her mother is also a scientist. Meg, who’s just about to enter high school, feels awkward and insecure. Her little brother Charles Wallace also feels like he doesn’t fit. But both are incredibly intelligent. In fact, Charles has the gift of reading people’s minds.

On a stormy night, someone who’s called Mrs Whatsit visits them. She looks like a tramp but in reality she’s a celestial figure (an angel). She confirms to them the existence of a “tesseract,” a shortcut or a wrinkle in time and space. It is through that “wrinkle” that she would accompany the two children along with a boy from Meg’s school named Calvin on an adventure to rescue their father from evil forces holding him captive on a different planet. Two other women similar to Mrs Whatsit join them: Mrs Which and Mrs Who. The three eccentric women are there to guide and protect them on their classic good-vs-evil journey.

1. Its portrayal of Jesus as being on par with great musicians and artists.

2. Mixing themes of witch-like characters with magical powers (the three women), magical planets and even an oracle and a crystal ball into a story with Christian undertones and biblical quotes is viewed as unorthodox or blasphemous by Christians. Non-Christians, of course, would find the inclusion of biblical verses unusual in a mainstream, popular fantasy novel.

Their first stop is on the magical planet Uriel where the most controversial scene of the book takes place. The children get to see the Dark Thing, a massive blackness that threatens to take over the universe. Mrs Which tells the children in a voice that rings out:

“Itt iss Eevill. Itt iss thee Ppowers of Ddarrkknesss!”

“What is going to happen?” Meg’s voice trembled. “Oh, please, Mrs Which, tell us what’s going to happen!”

“Wee wwill cconnttinnue tto ffightt!”

Something in Mrs Which’s voice made all three of the children stand straighter, throwing back their shoulders with determination, looking at the glimmer that was Mrs Which with pride and confidence.“And we’re not alone, you know, children,” came Mrs Whatsit, the comforter. “All through the universe it’s being fought, all through the cosmos, and my, but it’s a grand and exciting battle. I know it’s hard for you to understand about size, how there’s very little difference in the dize of the tiniest microbe and the greatest galaxy. You think about that, and maybe it won’t seem strange to you that some of our very best fighters have come right from your own planet, and it’s a little planet, dears, out on the edge of a little galaxy. You can be proud that it’s done so well.”

“Who have our fighters been?” Calvin asked.

“Oh, you must know them, dear,” Mrs Whatsit said. Mrs Who’s spectacles shone out at them triumphantly.

“And the light shineth in the darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.”

“Jesus!” Charles Wallace said. “Why, of course, Jesus!”

“Of course!” Mrs Whatsit said. “Go on, Charles, love. There were others. All your great artists. They’ve been lights for us to see by.”

“Leonardo da Vinci?” Calvin suggested tentatively. “And Michelangelo?”

“And Shakespeare,” Charles Wallace called out, “and Bach! And Pasteur and Madame Curie and Einstein!”

Now Calvin’s voice rang with confidence. “And Schweitzer and Gandhi and Buddha and Beethoven and Rembrandt and St. Francis!”

“Now you, Meg,” Mrs Whatsit ordered.

“Oh, Euclid, I suppose.” Meg was in such an agony of impatience that her voice grated irritably. “And Copernicus. But what about Father? Please, what about Father?”

“Wee aarre ggoingg tto yourr ffatherr,” Mrs Which said. 1Madeleine L’Engle, A Wrinkle in Time, (New York: Ariel Books, 1962; Reprint edition, 2017), 85-86.

Eventually the children are able to rescue their father and defeat IT, the story’s main antagonist who represents evil in the shape of dismembered brain on planet Camazotz.

The three women guiding the children explain to them that only through the work of great historical figures that evil has not taken over the world. From a Christian perspective, the conversation starts well: Mrs Who, who always talks in quotes, delivers a biblical verse (John 1:5), “the light shineth in darkness,” which is a reference to Jesus as a misunderstood person as the rest of the verse alludes (“the darkness comprehended it now”). However, in the following lines, he’s lumped together, as if he’s only a great moral teacher, along with artists, writers, musicians and scientists. Clearly, no true Christian would accept Jesus as being on equal footing with Buddha or even a great saint like St. Francis. For Christians, this heretical passage smelt of a new-age, Universalist view that all belief systems are equally fine.

Isaiah 42:10-13: “Sing unto the Lord a new song, and His praise from the end of the earth, ye that go down to the sea, and all that there is therein; the isles, and the inhabitants thereof. Let the wilderness and the cities thereof lift their voice; let the inhabitants of the rock sing, let them shout from the top of the mountains. Let them give glory unto the Lord!” 2Ibid., 64.

John 1:5: “And the light shineth in the darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.” 3Ibid., 85.

Romans 8:28: “all things work together for good them that love God, to them who are called according to his purpose” 4Ibid., 166.

I Corinthians 1:25-28: “The foolishness of God is wiser than men; and the weakness of God is stronger than men. For ye see your calling, brethren, how that not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble, are called, but God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty. And the base things of the world, and the things which are despised, hath God chosen, yea, and things which are not, to bring to nought that are.” 5Ibid., 194.

You might also like:

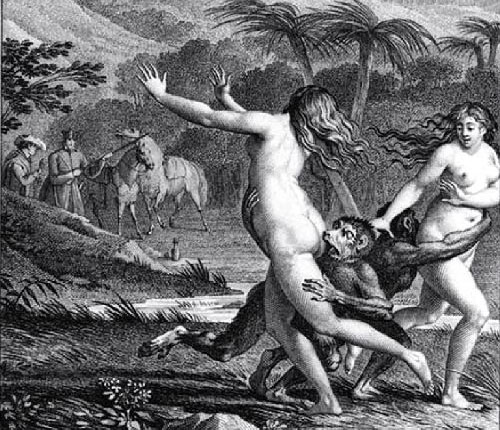

Candide: The shocking passages

Condemned by the French government and the Catholic Church: Read the controversial passages from Voltaire’s Candide (1759)

BOOK: CANDIDE

Roald Dahl’s The Witches: The paragraphs critics called sexist

Why feminist critics accused Dahl of being a misogynist? In its opening, Dahl wrote “all witches are women”

BOOK: THE WITCHES

Endnotes