In the climax of Of Mice and Men an angry mob is trying to find Lennie, a mentally disabled ranch worker who had just accidentally killed the wife of the boss’s son. Their intent is to deliver vigilante justice. Out of great concern, his lifetime friend, George, spares him the horrific punishment and shoots him in the back of his head before they find him. One of the reasons the final scene sends shivers down the reader’s spine is that George is now about to face the world all by himself. Surely there were times when George felt lonely while with Lennie because of the latter’s mental disability which occasionally affected their verbal communication, but he never gave up on his company, especially in light of their line of work. George tells Lennie those who work on ranches are, “the loneliest guys in the world.”

It’s remarkable that the novella manages to showcase the most prominent types of isolation in modern society. The book could also be read as a critique of artificial social boundaries. John Steinbeck created characters bound by class, race, gender, disability, ageing and type of work.

George, a farm laborer, understands his place in society whose members judge each other based on their class. He says to his friend:

Guys like us…ain’t got nobody in the worl’ that gives a hoot in hell about ’em.

Candy, an old handyman who lives on the ranch, is depressed after letting other workers shoot his old, crippled yet beloved dog in an act of mercy killing that would foreshadow the book’s ending. He was disturbed to see the dog treated as worthless, which didn’t bode well for his own future, and, above all, to lose a loyal companion.

Lennie’s innocence, a byproduct of his mental underdevelopment, prevented him from understanding barriers of race and gender. It didn’t make sense to him to be unable to visit and associate with a fellow worker who happens to be black. Crooks, whose name was a humiliating reference to a disability in his back, was the only black man on the ranch. Lennie’s surprise visit was not met with delight: “You go on get outa my room. I ain’t wanted in the bunkhouse, and you ain’t wanted in my room.” It’s possible that out of pride, he pretended to be irritated, although he might have become so accustomed to his isolation that he no longer feels comfortable around others, especially if they’re white. To be fair, there could be another reason behind his reaction: he feared brutal retaliation from his boss on account of breaking the racial rules.

Crooks eventually relents and lets Lennie stay in his room, then he explains how he deplores his isolation – “I can’t play because I’m black.” He asked Lennie how he’d feel if he were never to see his friend George again. Lennie, unable to comprehend hypothetical scenarios, thought that George had been harmed and started to show signs of panic and rage. Crooks assuaged his fears and in a flash of candor, he described his own feelings:

A guy needs somebody to be near him. A guy goes nuts if he ain’t got nobody…I tell ya a guy gets too lonely an’ he gets sick…Think I don’t like to talk to somebody ever’ once in a while?

Soon, also Candy, the old worker, shows up at the door but hesitant to enter. By that point, Crooks had a different tune and invited him in. The man who never receives visitors didn’t bother to hide his joy anymore for having both Lennie and Candy in his room. It turned into one the most heartwarming scenes in the book where race, age and disability (mental and physical) did not impede the three men from associating, albeit briefly, with one another.

The flirtatious wife of the ranch owner’s son is another person who was frank about her need for companionship, which she never found in Curley, her husband. We see her as a half villain, half victim character. It shouldn’t be assumed that her flirtatiousness was meant to result in illicit relationships. The possibility that she’s misunderstood crosses our minds when she complains to Lennie:

I never get to talk to nobody. I get awful lonely.

…

You can talk to people, but I can’t talk to nobody but Curley. Else he gets mad. How’d you like not to talk to anybody?

Curley’s wife is not the only one seeking ways to break her loneliness. Just like Candy keeps a pet, a familiar practice in our society, Crooks, the marginalized black man, finds a warm refuge in books. Other ways of finding companionship takes place in the shadows: the brief visit of George and the other nameless ranch workers to a whorehouse in town.

While the characters suffer from loneliness, they rarely speak of it. That’s not surprising because most people are too proud to admit they need companionship. On multiple occasions, George mutters to himself in moments of anger at Lennie “if I was alone I could live so easy.” But the truth is he never considered life without his friend as evident from sticking together even after Lennie committed monumental mistakes that cost them their jobs and threatened their lives. Crooks acted like he favored being lonely in his room. Candy abstained from speaking up to say his stinky, old dog is his only companion in life before his fellow workers took it outside to kill it.

This fate of loneliness is not unique to a 1930s American ranch. As novelist, Thomas Wolfe, succinctly put it:

Loneliness is and always has been the central and inevitable experience of every man.

In Western countries, tens of millions of people live in single occupancy homes. More families than ever are broken up. Longevity for decades has been increasing. Bigger homes and wider backyards in the suburbs add further spaces between people. Technology from the telephone to digital communications reinforce our isolation by selling us the illusion that we can do away with face-to-face, physical contact.

Loneliness seems to be on the rise, but even if we were to reverse the trend, we’d still find it unavoidable. It’s so ingrained in our existence that a journalist, Norman Cousins, once gave it the credit for everything we have ever accomplished or invented:

The eternal quest of the individual human being is to shatter his loneliness.

The odds are often stacked in favor of our sense of isolation: an ironic example is that if Crooks, a victim of racist marginalization were living in a black community, he’d still experience the same due to his disability. And if he were not disabled, the burden of alienation would still follow him for being the most learnt and intelligent one in the community.

Those of us in relationships are not immune. The tragedy at the core of every loving, lifelong relationship is that it will most certainly end in the death of one partner, leaving the other desolate. That’s the reason we’re captivated by the rare story of an elderly couple dying minutes or hours apart. Similarly, most parents know all too well about their impending “empty nest syndrome.”

Audrey Hepburn was misguided to believe that when nobody needs you, when you have “nobody to make a drink for”, your life is over! Loneliness doesn’t have to be a state of emotional torment. Some of the greatest minds transformed it into a time of solitude. Artists, poets and writers took it as an opportunity to explore the depths of the wellspring of creativity. Indeed, solitude can be the time to enjoy tranquility, learn about oneself, combat stress, disconnect from digital life, think through persistent problems and wade through the works of great intellectuals like Jean-Paul Sartre who’d tell you that “hell is other people.”

You might also like:

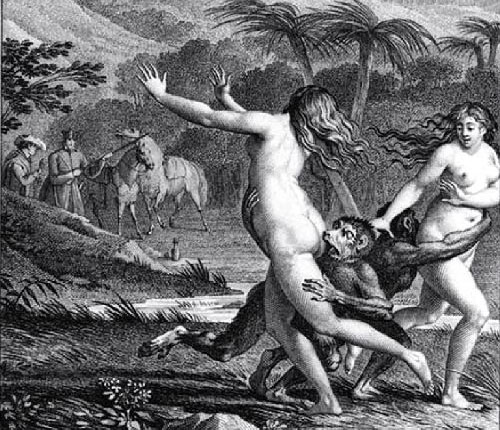

Candide: The shocking passages

Condemned by the French government and the Catholic Church: Read the controversial passages from Voltaire’s Candide (1759)

BOOK: CANDIDE

Voltaire’s radical views on race and slavery

Understanding Voltaire’s view on race and slavery through the eyes of Candide

BOOK: CANDIDE